Familiarity is the surest cure for fear. I remember waking up in the crypt for the first time, one rotting corpse among many. When I returned two years later, the room almost looked innocuous in the flickering torchlight.

It is sometimes best to go back to the beginning, but the devastation of the Third War made such an action impossible for me. Yet I could return to my second beginning, the birth of my undeath. Hatred animated me in the dark days after my resurrection, when I longed to hear the cries of those who had left me to die. I could only feel that anger for so long, however, before its uselessness became apparent.

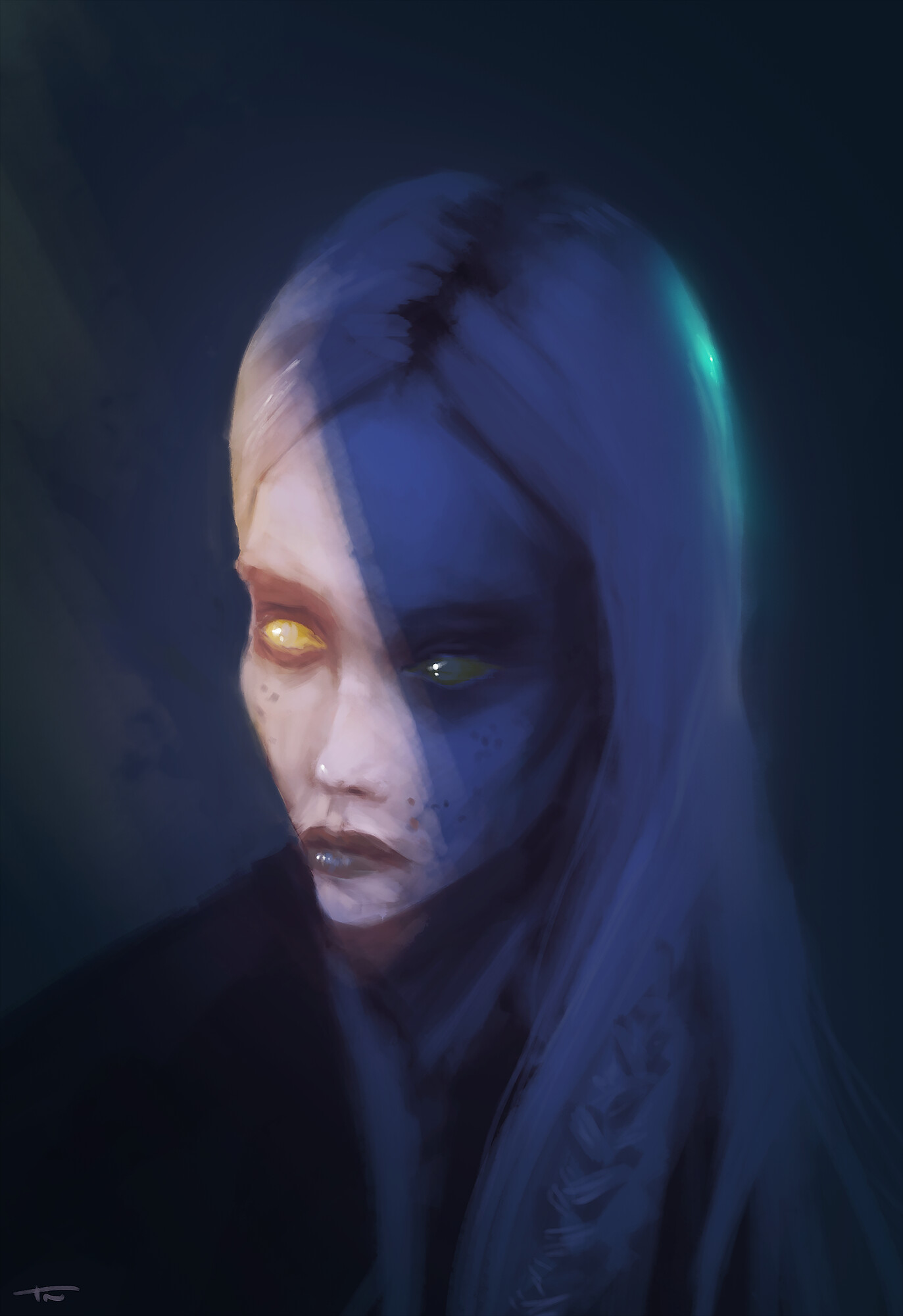

Even in life I looked fragile, like a stick figure given flesh, and death has added its tell-tale mark. My light green eyes are gone, replaced by dusty sockets. The skin on my bones, once simply pale, now has the ashen quality of undeath. Though most Forsaken let their dried hair grow wild, I have maintained the close-cropped style of my life, the dark brown color bleached out to dun. Like most of my brethren, my clothes consist of castoffs; faded black trousers and a tattered gray great coat that reaches to my knees.

“Did you rise here too?” she asked, in a hollow voice. “I can scarcely believe it at times. I feel like I’m trapped in a terrible dream. Do you think that sometimes?”

I was unsure of how to respond. Most Forsaken detested their undead state though a few relished it. I turned my bitterness to the outside world when I first arose. Others, like her, turned it inwards.

“It is a strange way of life,” I replied.

“It is not a way of life! I remember how wonderful everything once was. I wish I had forgotten.” She paused, as if unsure of herself. “My name is Velle.” She extended her hand. There was an odd sheen on her arm. Looking closer, I saw that part of it had rotted away. She had sown flesh-colored silk over the wound’s opening. I’d seen that sort of thing before, not uncommon among those that strove to maintain a semblance of their old selves.

|

| Velle, by Norbert Toth |

I asked her if she lived in Deathknell, the settlement around the Crypt. She shook her head, explaining that she resided in Brill as a servant to the Executor. She went to Deathknell on the rare times she was granted a holiday.

“Why not Undercity?” I asked.

“Lordaeron!” she contradicted, angrily.

“I’m sorry, Lordaeron.”

“I don’t wish to see it anymore. Did you see it? When King Terenas ruled?”

“Yes, though I can’t recall it very well.”

“Lordaeron was a kingdom of light back then. I... don’t want to see it now. Do you understand that?”

“I do.”

“Most don’t. But I suppose we’ve been cursed eternally.”

“Maybe. Still, we could make things better for ourselves. There’s no reason why we couldn’t—”

“No. The Light is gone from us.” With that she began crying in harsh dry sobs that sounded like coughs.

I apologized, though she insisted that there was no need. Together we went up the steps to the surface world, rotting under a magic-scarred sky. I had returned to Deathknell with curiosity, but meeting Velle reminded me of the old despair.

In the days when the living still ruled Tirisfal, Deathknell had been a provincial farming town called Seven Pines. Like most towns, it fell to the mindless undead armies of the Scourge. When our Dark Lady Sylvanas broke free from the Scourge, she used the ruins of Seven Pines as an area to bring more of the Forsaken into the world. I don’t know exactly when the name changed to Deathknell; everyone started calling it that in the early days of the Forsaken. It is a simple place, a huddle of buildings in various states of disrepair amidst a dying forest. Deathknell has faded from importance since then. Most of the dead and undead that could be made Forsaken have already undergone the process.

With its primary purpose gone, Deathknell has become a ghost town. Mindless zombies still roam the forest, the results of failed resurrections. The town lacks an inn, so I spent the night resting on the floor of what had once been a church. A priest stood there throughout the night, uttering obscenities to an unseen congregation.

The ramshackle and desecrated church is a grimly appropriate inversion of Lordaeron. More than any other human kingdom, Lordaeron defined itself in the faith of the Holy Light and the great strength of the church. White-garbed priests preached peace and unity in all corners of the kingdom. It was the church that defended the downtrodden peasantry against rapacious nobles and warlords of Lordaeron’s early history. In more recent times, the church acted as a beacon through the darkness of the Second War.

This is not to say the church was flawless; far from it. Corruption afflicted it just like any other organization. Yet in most respects, it lived as it preached. Even the Archbishops (with a few notable exceptions) led simple lives, tending to the faith’s ideals. Just as each Lordaeronian was born into the love and unity of the Light, each Forsaken is greeted with the hatred and isolation of shadow. That Lordaeron became so stricken with the plague of undeath was the cruelest of ironies.

For all the talk about undeath being a curse, it does have advantages. One is the ability to sleep almost anywhere at anytime. I found this refreshing after a life of insomnia. Sleep no longer brings the same restful feeling it did in life, but it is a brief respite from awareness.

Velle was still present the next morning. She explained that she was obliged to return to Brill, and I offered to accompany her. Velle accepted and we began the journey before noon.

The Tirisfal Glades were once famed for their natural beauty, a land of flowering meadows and verdant forests though not too wild or rough. The hand of man nurtured it into a garden realm. But that was long past. A spectral green haze now fills the sky, and newcomers cannot always tell the difference between night and day. The land is lost in eternal twilight. Sickly and blackened trees ooze sap from innumerable wounds, while the streams run foul with rot. Perhaps I have lost perspective but I cannot help thinking that the new state of Tirisfal Glades still possesses an eerie beauty. I know that I am not the only Forsaken who thinks this.

Velle could not disagree more. As we traveled in the shadowed half-light, she only spoke to recall the beautiful lands of her life. We passed the road leading to Agamand Mills, a ruined farm haunted by the vengeful ghosts of its former owners. She claimed she had known one of the Agamand family, though she could no longer remember which one. No one has yet figured out what determines the amount of memory a Forsaken holds of their lives. Some were raised with virtually no memory, even having to relearn speech though such extreme cases were rare. Others knew everything that had happened to them. Most fell in between, remembering the basics but not the details. Velle described the personality and traits of her Agamand friend at great length, yet the name eluded her. She said she could not even be sure of the Agamand’s gender, though she thought it had been a man.

We arrived at Brill sometime on the second night of travel. I gave my leave to Velle and told her that undeath did not have to be all misery. She only shrugged in response before waving farewell. Brill was a fitting town for her, most of the population being lost souls who think only of the past. Some even try to deny their undead state.

The Gallow’s End Inn is a perfect example of the town’s despair. The common room is brightly lit from the flames of a hundred candles. The tables are kept immaculately clean; far cleaner, in fact, than the tables used by the living. The attempts to make it seem like a place of life are ultimately futile. Nothing dispels the aura created by the mobs of living corpses that occupy the parlor at all hours of day and night. Unlike a normal tavern, the sound of conversation rarely rises above a dry whisper.

Sardius Astron was a whisper-thin Forsaken who spent every evening at Gallow’s End. In life, he explained, he had been a respected town burgher. In death, he administered the defenses of Brill. Even in Tirisfal Glades, the Scarlet Crusade and the Scourge threaten the safety of my people.

“I had a home and a family here once. Sometimes I can even remember what they looked like,” he wheezed. Sardius’ withered frame was only covered by scraps, revealing the terrible wounds splitting his belly and chest. “What brings you here from Undercity?” he asked me.

“Curiosity.” I briefly outlined my plans to see and learn more of the world.

“You wish to return to the living, I take it? To be alive?”

“Not as such.”

“Then why do you go among the living? You know that they will all hate you. They have nothing to offer us, Destron.”

“What makes you so certain?”

“The hatred they bear for our kind. The orcs are no different from the humans.”

“Is this true of every orc?”

“It is true for enough of them. Your goal of understanding is fruitless, for they will not understand us.”

“What is your definition of a worthy goal, if I may ask?”

“Death! It is the great leveler. Just as it ruined Lordaeron, it shall one day turn this great world to dust. Death is inevitable; it’s the only goal worth striving for.”

“And how are you working towards death?”

“I aid our Dark Lady, help her destroy the living. Not in the same direct way as do the Deathguard or the Apothecarium, but I help. You can help as well. We’re always in need of a mage.”

I wondered what I truly hoped to accomplish by traveling. Sardius was right, after all. Even the races of the Horde bear no particular love for the undead. But what was my alternative? I had already spent years in the catacombs of Undercity, stoking and nurturing my rage. Surely anything would be better than that.

As if hearing my thoughts, Sardius laughed hoarsely.

“You won’t accomplish a damn thing, Destron. They took everything from us, and you won’t get it back wandering around among the living. Face the truth. Coward.”

Brill was the first town in the region to fall to the Plague of Undeath. Kel’thuzad, the creator and bringer of the Plague, once resided in a small home on the western edge of town. Angry Forsaken have since burned it to the ground.

In the third Tuesday of each month is a celebration called the Remembrance, a festival exclusive to Brill. The townsfolk gather in the center of town, wearing startlingly life-like masks. The lampposts fill with searing magical light, creating a strange parody of the sun. The Forsaken spend the day talking of farms and gossiping of those long since dead or departed. The masks drop at nightfall, the multitudes weep.

Brill was a picturesque little town before the Plague, and served as a trademeet for local farmers. A new industry has taken hold within the ruined streets. Daring Forsaken plunder the Scourge-haunted ruins of abandoned villages and farms, looking to retrieve mementos of the past. These are then sold to the Forsaken of Brill who will buy nearly any item of cultural value.

Mindra Vanar was one such artifact merchant, operating out of a tattered and unspeakeably squalid wagon in the city limits. Heirlooms, religious icons, and rotted clothing surrounded her in messy heaps. Mindra’s physical condition was not much better than her wares. Her abdomen bloated grotesquely and veins ran visibly through wet green skin.

“Pretty much everything of value in Brill was destroyed or taken. To get anything of reasonable quality, you have to go out into the countryside. A lot of the villages there were so small that they became undead before anyone had time to evacuate. Thus, they left their possessions behind,” she explained.

“It must be hard to find things in good condition.”

“Quite true, quite true. When I first started, a mere year after our Dark Lady freed us, I could get things like paintings and fine dresses. Not any longer though. Now it’s all weapons and statues. Every now and then someone gets lucky and finds something delicate that escaped the elements, but I haven’t had a find like that in months.”

“Why are these artifacts so popular?”

“Mostly the buyers wish to be reminded of their lives. A lot of them deny it, but their protests aren’t very convincing.”

“You won’t be able to keep retrieving artifacts forever though. You’ll run out sooner or later.”

“Sooner. I have to go farther afield each time. Tirisfal’s more or less cleaned out, except for the parts that are too dangerous. I might start heading to Silverpine Forest. There’s a thousand abandoned homesteads out there. Inconvenient, but what else is there to do?”

“Are these relics sold in other places? I lived in Undercity for some time, but I never saw anything like this.”

“Just Brill. I knew a relic trader who went down to Tarren Mill to make a sale, and they laughed him out of town!”

“If I may ask, why do you take part in the relic trade?”

“It’s something to do. This way I don’t have to think about my son and husband. I do not want to end up like the people here in Brill. Maybe because I sell the relics, I can just view them as merchandise, without any sentimental value,” she cackled.

*********

A new arrival stands on the windswept hill south of town, and a spectacular one at that. The zeppelin tower stabs into the wounded sky, its top pointed like a witch’s hat. Zeppelins are another invention of the brilliant goblin merchants of the south (I also have to thank the goblins for creating the “Photo-recorder” that I used to take many of the pictures that fill this volume). The zeppelin connects Tirisfal with the orcish homeland of Durotar and the far-off jungles of Stranglethorn Vale. These remarkable aircraft are our great connection to the outside world, though many of the visitors arriving in Tirisfal leave for Undercity rather than Brill. Though the living were openly despised in many parts of Undercity, most still find it preferable Brill’s abject misery.

Though I was tempted to go to Undercity, I decided to travel to the east. The farther east one goes, the darker it becomes. I did not relish the idea of going into the cursed Plaguelands, yet I deemed it necessary. I wished to get the worst out of the way before going to more pleasant lands in the south.

After a day at Brill (though it felt longer), I left in the middle of the night, walking under the moon’s sickly glow. Following the weed-infested road east, I passed by the gates of Undercity, once known as Lordaeron’s Capital City. Lordaeron was the greatest of the human nations for a time, important enough to become synonymous with the entire continent. The kingdom stretched in a vast C-shape across the map, starting in Southshore and arcing through Silverpine and Tirisfal before terminating in city of Stratholme. The old ruins of the capital still stand under the ragged Forsaken banner of a broken mask.

The thickly-forested hills of eastern Tirisfal were always less cultivated than the rest of the region. The next morning, I passed a band of orcs, returning to Undercity after a long campaign against the Scourge. I spoke with them for a while but they were clearly uncomfortable with my presence. I cannot honestly say I felt easy towards them either. I left after saluting them for the courage against our common enemy to the east and north.

It’s strange to think that just a few decades ago, orcish war parties raided Tirisfal, leaving a trail of dead bodies and burning villages in their wake. After the Scourge, they (along with the Darkspear trolls and the tauren) were the only ones who accepted us as people. Of course they had changed as much as we in recent years.

Soon after that, I met a Forsaken standing by the side of the road. Even for one of our kind he was in terrible shape. A gaping wound yawned where his nose and eyes should have been. He pushed a cart full of metal scraps.

“Hey you!” he shouted in an rasping voice.

“Yes?”

“Did you pass a bunch of those Light-damned orcs? They came marching down here a little while ago. We’ve let this place fall to ruin while those greenskins march around like lords.” He let loose a string of invective.

“The orcs extended their hand to us when no one—”

“Wrong! They just want to finish what they started back in the Second War. To Hell with Thrall and all the other greenskins!”

I sighed inwardly at that point. Was I simply being close-minded? I came to learn, yet it seemed like no one had anything worth teaching. There was a snapping sound and he stumbled, his leg bone protruding through his tattered clothes. The cart, a rickety one-wheel model, fell to the side and the scraps clattered noisily on the road.

“Aw, damn,” he wheezed. “Could you help an old man out? Life was hard enough for me, I never asked for a second one.”

Those who died of the plague have undergone something so terrible that no living person can ever come close to comprehending it. Bigot or no, he was Forsaken. While he set his leg bone back into place with a rusting shackle, I put the scraps back in the cart and offered to push it for a while.

“That’s very kind of you. Maybe the Light isn’t entirely gone from this land. My name’s Orriv, what’s yours?”

He was headed back to his home in the east, but said he could reach it before nightfall if I helped him. Orriv scavenged odds and ends from ruined farms to the east. Then he would take them to Undercity to be sold. Unlike Mindra, Orriv only gathered utilitarian items. It might seem odd that the Forsaken would care about money or commerce, but such things still serve a purpose. We do need food and drink, though in vastly lesser amounts than the living. More important was the fact that, even if some would deny it, many Forsaken still have dreams and hopes (though these are often cruel or mad in nature) that require money to achieve.

“It just fetches a few coppers, but that’s all I need,” he explained.

Orriv was in his fifties when the plague struck, a crippled veteran of the Second War living a hand-to-mouth existence in Brill. He recalled the Second War with what sounded like joy, though I wondered how much of that was simply selective memory at work.

“I fought in the earliest campaigns of the war. As soon as those poor folk of Stormwind came up here to escape the orcs my sword was ready! What a sight it was when we marched out for the first time, right from the capitol, the will of King Terenas in flesh and steel! A lot of us died, but there’s no shame in dying to defend your land from monsters.”

“You must have traveled a great deal in your time.”

“I got all the way down to Khaz Modan. Heh, those dwarves brew some damn fine beer. I served under Uther the Lightbringer, did you know that?”

I shook my head.

“Aye, he had a presence like you wouldn’t believe. Like fighting alongside a god. That bastard Arthas will rot in Hell for what he did to Uther.” He gave an odd whimpering sound.

“Did you get that wound in the war?” I asked, trying to steer the conversation away from Uther, one of the greatest heroes of Lordaeron.

“Indeed. I was on patrol in the Wetlands when a bunch of orcs ambushed us. They had one of those ogres with them, and the beast damn near shattered my leg with his cudgel. I gave them hell though, took down two orcs before I was clubbed. I couldn’t really walk after that... funny thing really. I can walk now, do things with my bones that they couldn’t have when they still had their full set of flesh on them. Still life wasn’t all bad. We took care of our own.”

We arrived at his house, which was little more than a shack in the forest. Orriv insisted that I have something to drink though he apologetically explained that he had precious little worth drinking. The inside was a filthy mess, the rotten wood of the walls and ceiling hosting a forest of mold. A sword, still in decent condition, occupied a place of pride over the ash-choked hearth. It was the only thing that didn’t look neglected. Orriv reached into a broken stove with a skeletal hand and took out a clay bottle.

“This is some wine I got ages ago. Don’t know if it’s any good, but I reckon you can’t really taste much anyway.”

He was right. My sense of taste and smell had atrophied terribly, though not as badly as some others. As a Forsaken, most physical sensations are experienced as vague memories even as they happen. I felt vaguely guilty about accepting the bottle, seeing as he had so little. Nonetheless I took a draught, leaving a sour taste in my mouth. The wine had aged into vinegar.

“Not much, I know. Everything here’s rotten though. Hell, just look at us! Anyhow, I really thank you for the help you gave. Made death a bit easier for me.”

He walked outside with me, and I noticed a garden on the other side of the shack. It was small and modest, its roses in a state of perpetual wilt. By the looks of the short stone wall around it, the garden had probably been part of an older structure. A partially buried foundation next to it confirmed my suspicion.

“Do you keep this garden?”

“In my spare time. Which I have a lot of!”

“It’s beautiful.” In fact it was, possessed of entropy’s strange attraction.

“Eh, not really. It’s something to do when I’m not gathering scraps or thinking of better times. Things will get better. I may moan a lot, but I’ve got real loyalty to our Dark Lady. Once we set the Scourge straight I know she’ll get talking with Stormwind and Ironforge again. First we’ll take down the Lich King, and then we’ll kill every last damned orc and troll. Better times son, mark my words.”

Bidding him farewell, I continued on my way.

*********

“Can you fight?”

It was a little more than a day after I left Orriv. I pushed deeper into the dying and discolored forests of eastern Tirisfal, still searching for understanding. Then I ran into a war party of ten Forsaken. Seven of them were Deathguards, the rank and file of the Dark Lady’s armies, while the other three were simply irregulars. Clad in the tatterdemalion purple cloak and hood of his rank, the leader called out to me.

“Can you fight? Yes or no?”

“Yes, I’m a mage. And I will fight.”

“Good! In the name of Lady Sylvanas, I induct you into the Great Company of Death! Have you served before?”

“No,” I answered.

“Then just do as I tell you. My name is Deathguard Harrin, follow my orders.”

The old flame of hate in my heart was stoked when I heard that name again: the Great Company of Death. It was a term commonly used to refer to the Deathguards as a whole. Unlike the old army of Lordaeron, the Deathguards are a wildly heterogeneous bunch defined by skill and fury. The Deathguards have lately become more disciplined thanks to orcish influence. While the decentralized nature of our army gave commanders a good deal of freedom, it ultimately became more of a liability. I would soon find out why.

“What happened?” I asked. We were going at a steady run. Forsaken can run longer than any other race, who inevitably fall behind from exhaustion. Though we still have our physical limits, we possess incredible endurance.

“The Scarlet Crusade happened! There was a massacre, we got the report yesterday. You’ll see it soon enough.”

A shrill cry went up from the party at the mention of the hated Scarlet Crusade. The Scarlet Crusade is the bastard child of the now defunct Order of the Silver Hand. As Lordaeron fell, the lands around it turned into vast slaughterhouses, some of the human survivors became consumed with rage. It’s precise origins remain a mystery. What is known is that red-armored fanatics walked the dead lands soon after Sylvanas’ secession. They did not distinguish between Scourge and Forsaken; they killed all undead on sight. It did not stop there either. Even humans or dwarves who walked into their realm were murdered on suspicion of being afflicted with the plague or of having undead sympathies. They threatened all of the north from bases in Tyr’s Hand, Hearthglen, and the Scarlet Monastery. The Monastery is located in Tirisfal, serving as their headquarters for the region.

We soon reached the massacre site. Broken and mutilated bodies were scattered around a defiled Forsaken banner. Sharp stakes ringed the site, and each crowned with a burned skull. A howl went up from the Deathguards. In their cruelty the Scarlet Crusaders carved words into the headless Forsaken corpses:“PURIFICATION” and “THE FATE OF THE DAMNED”. They covered the bodies with icons of the Light, made of holyoak and silver. The Crusaders believe that the symbols prevent us from rising again, though once a Forsaken is truly dead he or she will be forever so.

“We should bury them,” said one of our group, an irregular named Alyna.

“Later. We’re going to attack the Monastery, kill at least two Crusaders for every Forsaken that has fallen here! We can bury them later if we wish, vengeance is our goal now!”

Moving at a quick pace we went to the high plateau that dominates northeast Tirisfal. It is here the Scarlet Monastery stands, not far from the desolate North Coast. In times past it was the greatest repository of learning in human lands, a place for the devout to focus on the Holy Light, which the wise say is a part of all thinking beings. A few of the holy men fled after the Plague; most died. The Crusade found it an ideal residence.

It was a hard journey even for us. The once proud roads of Lordaeron have fallen into disrepair, and the terrain was often uphill and difficult. We passed atrocity scenes two or three times a day, similar to the one we saw earlier. The victims were not always Forsaken; some were luckless humans, or deserving Scourge.

Looking back on it now, I have mixed feelings. I did the right thing in helping the Deathguards, of that I am sure. Yet going up the path to the Monastery I had returned to my old self, the way I was in the days after my resurrection. I anticipated the coming bloodshed with a cold satisfaction. That said, there is something particularly vile about the Crusade. Most of the Scourge are mindless, mere extensions of the Lich King’s will. They have no choice or interest in what they do. However the Scarlet Crusaders still possess the capacity for reason. They simply choose to ignore it, and twist the Light so that it becomes a faith of cruelty.

Our war party came within sight of the Scarlet Monastery after three days. We had been lucky in not encountering any Crusader patrols on the way. The jagged and barbed spires of the monastery jab skyward, and we all heard a faint chanting from within. I vaguely remembered hearing the same hymn it in the churches of my youth. We crept slowly in the darkness of the trees and wilted undergrowth. Guards stood all around the front of the monastery. I counted at least fourteen. Harrin motioned to me, and I inched forward.

“Fire,” he whispered, pointing to the guards. “We’ll show them purity.”

The stealthier Forsaken were already in place, ready to strike when my bombardment ended. Fire danced around my withered hands, coalescing into a burning sphere. I let it loose and it exploded with a resounding boom. Two guards were killed instantly in the conflagration and the Deathguards hidden around them struck quickly and ruthlessly.

I provided support as best I could, though Scarlet priests channeled the energy into spells of their own, healing the guards’ wounds as they opened. No Crusade arcanists were present. The Scarlet Crusade distrusts arcane magic, though they do not shun it entirely.

We could not afford a sustained strike on the Monastery. Our goal was simply vengeance. Quickly running to a hidden mountain pass that our scouts had found earlier we made our escape. Only two of our number fell in battle and we were flush with victory. Avoiding the trail leading to the main road, we kept to the woods.

I’ll confess that I never had a very good grasp of tactics or strategy. Since then, I have at least learned that it is a terrible idea to make an attack on a heavily fortified enemy stronghold in the heart of their territory when you have no backup and few soldiers. I know it probably seems obvious to any reader, and I can only blame my own ignorance and fanaticism.

When Harrin had judged us as safe from pursuit, we rested in a grove of rotting trees. My companions exulted in the memory of Crusader death cries, and relished the hollow triumph of revenge. Many Forsaken tend to have dampened emotions, but in some circumstances buried feelings can roar to life. Unfortunately, it usually comes as rage or melancholy. I was simply weary, and entered the strange half-sleep that Forsaken undergo, where one feels dimly conscious of the waking world but unable to affect or control it. That said, loud noises work just as well to wake the undead.

The noise came as a yell of alarm from Harrin, followed by the whoosh of arrows cutting through the air. Shouts bellowed from the trees and I saw a giant of a man emerge, decked in blood-red armor. Bald and hideously scarred he carried a burning torch in one hand and a book in the other. His armor was festooned with bones and pieces of his victims, the icon of the Crusade crudely stitched on his yellowed tabard. Staying low, I fired bolts of magic at him. He had to have been at least hurt yet he continued chanting and yelling without pause as howling crusaders swept out from the trees with wild eyes.

Man for man, the Forsaken have the advantage. We were surprised though, and outnumbered. At least one Deathguard fell in the first rounds and died his last death. It is difficult to recount the battle clearly. When one is in the midst of it, the only reality is the struggle to get through in one piece. It seemed like hours, but it could not have been more than a few minutes before we were forced to retreat.

I fired more spells and I think I killed their leader with a fireball. The sodden trees of Tirisfal do not burn well, yet luck was with me on that day as fire sprang up above the crusaders. One of them got close to me, swinging a vicious looking sword and I held him off with the fallen Deathguard’s iron rod for as long as I could.

Then it was over. The crusaders were gone, just like that. The fire in the trees sputtered and died. It was not much of a victory. Harrin, another Deathguard, and I were the only survivors. In fact, the crusaders had not outnumbered us by very much. They only numbered eight in the battle, while there were five of us. Harrin said some of the crusaders fled, though in my experience they rarely run from battle. Most prefer to die fighting their enemies.

Though we had won, we knew that there could easily be other crusaders still on our trail, so we made haste and reached the main road after four days in the wilderness. The other survivor, a man who had forgotten his real name and called himself the Cutter, spoke to me one night while Harrin rested.

“Harrin’s in big trouble you know,” he said.

I had begun to suspect that, so I nodded.

“Wasting troops on a foolish attack... maybe back in the old days, when all we wanted to do was to personally kill as many Scourge and crusaders as we could. Not now though.”

“Would we get in trouble for following him?”

“Us? No, we were just helping the war effort. No skin off our backs. Good thing too, since I don’t have any skin left over there,” he laughed.

“What will happen to Harrin?”

“He’ll probably be demoted and sent somewhere else that’s less important.”

The Forsaken are reluctant to execute their own. While it seems that we would have a limitless supply of new recruits by raising the troops we kill in battle, it is less simple than it seems. It is harder to raise a Forsaken than it is a mindless zombie or skeleton. Furthermore, most Forsaken hate necromancy with a fanatic intensity. Besides all that, a former crusader unwillingly raised as a Forsaken would almost inevitably rebel against whoever raised him. Free will is a key part of Forsaken identity.

We finally reached a small camp on the intersection of the trail to the Scarlet Monastery and the main road, where I spent two days recuperating. Harrin left for Undercity soon after we arrived and I don’t know what became of him. A strange sense of failure began to plague me. I had started traveling to learn about the world. So far, I had only discovered hate and rage. Again I want to stress that I do not consider the Crusade to be ethically equivalent to the Forsaken or the Horde. The Scarlet Crusade is an organization of evil. Yet I cannot deny that I felt joy when they died at my hands. Violence was inevitable, and I suspected I would see much more of it before I was through.

I recalled the history of the Scarlet Monastery with a twinge of guilt, even though its original purpose had been twisted beyond all recognition. The Scarlet Monastery was once called Terminon Monastery, in honor of a cruel and ruthless baron who renounced his dark ways at the very spot where it stands. The period after Lordaeron established its boundaries was a troubled one for the fledgling kingdom. While the Church of the Light took root in the east and in the royal court, many of the nobles held fast to the brutish gods of the old Arathi pantheon.

Lordaeron was lucky to escape the civil wars between king and nobility that tormented the southern kingdom of Stormwind. The Lordaeronian noble houses all stood together through wars against trolls and rival human groups, and this created a feeling of solidarity that lasted for generations. Disputes were settled with the ritualized combat of the tourney, which was still popular in my youth.

Of all the nobles, Baron Terminon was the most ambitious, wealthy, and powerful, and he finally sparked an insurrection against the king. He twice routed the royal army while marching through Tirisfal. The night before he prepared to sack a loyalist town, the priest Estellian came to him, accompanied by a pair of unarmed peasants. By dawn, Baron Terminon renounced his rebellion. He joined the church and gave all of his considerable holdings to the king.

The other nobles all held Terminon in great regard. When he joined the Light, many of his fellows did the same. This event, combined with gradual social and economic change, spelled an end to the power of the landed gentry. The king ruled from that day forward, his power shared by the church and civilian advisors.

I left the nameless camp, heading east on the main road. I arrived at the Bulwark in three-and-a-half-days. The Bulwark is exactly what it sounds like: a crude barrier between Tirisfal and the Western Plaguelands. In the early days of Sylvanas’ revolution it was a site of near constant battle, the tireless Scourge armies heedlessly charging through the narrow mountain pass. Now the situation is reversed, with Horde warriors (of which the Forsaken only consist a slim majority) preparing for excursions into the Plaguelands.

A noble group called the Argent Dawn also has a presence at the Bulwark. The Argent Dawn is perhaps what the Scarlet Crusade should have been. They are devoted to combating evil in the world, particularly the Scourge. The Dawn is not a band of angry zealots. All races, from human to troll and even Forsaken, are welcome within their ranks so long as they prove themselves. Given the danger present in the Plaguelands, I decided it would be wise to get traveling companions. Fortunately, there was a Horde scout party of twenty headed to the Isle of Caer Darrow that was happy to have me along.

Hiyas.

ReplyDeleteNew reader here; hopped over from the 'Spotlight' section of the main WoW page.

Speaking of the game...

WOW.

Sites like yours give a 'human' side to the game, as well as provide we RPers a view of the World which we play in to some who may view it as 'just another dumb game'.

There's a real story behind it; and writing such as yours is the perfect vehicle to get one in minddset with it.

Thanks. I'm DEFINITELY gonna have to subscribe. Travel on, good sir!

/salute

i kno ive been commenting alot lately but its becus i read ur work and made an account like 3 zones before i finish readin so i wanna ask u a question how did you really die??

ReplyDeleteThanks for the comments.

ReplyDeleteWhat exactly do you mean when you talk about subscribing? You don't have to subscribe to read this blog, and I'm certainly not charging for it.

Altray: Destron died of hunger and exposure in a refugee camp. I think it's mentioned somewhere in one of the Lordaeronian zones.

I like the idea of the Forsaken scavanging for trinkets, since it's similar to the way the living tend to behave in quite a few zombie filsm. Interested role reversal that shows a human side to the Forsaken.

ReplyDelete