((This section is dedicated to Niobrara.))

*********

I grabbed at the railing as another blast of icy wind crashed into the dirigible, the wooden hull swinging like a pendulum. The pilot spun the wheel in an effort to stay on course as crewmen scurried across the deck. The passengers could do little more than hang on to anything in reach: ropes, riggings, and chains.

“We’re almost through!” shouted the captain at the top of her reedy voice.

The deck dropped out from beneath my feet as the wind flung it to the side, and my chin hit the rail with a loud crack. Not sensing anything broken, I kept my grip firm, trying to get a glimpse of the Borean Tundra.

We were flying along the western coast in an airship called the Mighty Wind, going past the vast iceberg armadas, grander and loftier than even the greatest vessel. Pale curtains of variegated light shimmer in the sky above the icy ocean. The Borean Tundra offers some of the most spectacular views of the northern lights.

At last the winds died down as we began our flight over the Borean Tundra’s frigid desolation. It is a land beautiful in its harshness, a stony plain of lichen and stubby grasses spreading as far as the eye can see. Angular rock formations in gray and black dot the landscape like the monoliths of Arathi, the freezing winds molding them into the strange shapes of dreams.

Like many seemingly empty places, the Borean Tundra is rich in life. Herds of woolly rhinos and mammoths trundle along the steppes in search of grazing land, watched from afar by fearsome dire wolves. Heated springs bubble amidst the cold, giving refuge to an astounding variety of bacteria.

This too is threatened by the Scourge. The Lich King’s presence had weakened by the time of my arrival, his minions driven back by the courage of the Horde and the Alliance. But many of them hold fast, their festering contagions eating away at the land.

“There it is!” proclaimed Torgak, an enthusiastic orc warrior standing at the prow. “Warsong Hold! The might of the Horde made manifest!”

Looking ahead I could see it, looking like a giant spearhead thrust into the ground, wreathed in the black smoke of the forge. Warsong Hold is the nerve center of Horde operations in Northrend, and the Warchief spared no expense in its construction. He had hired a small army of goblin contractors to help make Warsong Hold the greatest fortress on Azeroth.

While perhaps not unequalled, it is certainly among the best. Goblin engineers built walls of enchanted steel and stone, able to shrug off shells from even the largest Alliance cannons. Machines rumble inside its metallic depths as tremendous smithies produce weapons for the Horde’s armies, using rare and powerful Northrend metals. Greater still are the brave souls defending Warsong Hold, warriors hand-picked for their skill.

Anyone who’s spent any time in Orgrimmar cannot help hearing about Warsong Hold. The fortress is hailed as a bold new development in Horde military science. Some question the accuracy of this statement, as goblin contractors played a major role in the design. However, more than a few of these goblins had fought alongside the orcs during the Second War, and it is fair to say that their motives for building Warsong Hold were not entirely mercenary.

Warsong Hold stands at the center of Mightstone Quarry, a bewildering network of mine shafts and excavation pits. Teams of peons toil at the stone faces all through the day, though large sections are empty and cordoned off by crude barricades. Smoke pours out from camps and field kitchens, joining the pall from the furnaces. There’s no doubt that Warsong Hold (and Valiance Keep, its Alliance equivalent) will also do its share of harm to the Borean Tundra. It is a necessary sacrifice, however, and I trust that the tauren will be able to ameliorate the damage when the Lich King is defeated.

I scanned the edge of Mightstone for signs of a zeppelin dock. Towering fortifications are embedded into the windswept mesas surrounding Warsong Hold, but I saw no place for The Mighty Wind to end its journey. Instead, the pilot began to move the airship around the citadel. Soon enough I saw her destination, a colossal zeppelin hangar on the Hold’s upper levels. Chains the size of wyrms hold steel blast doors at the hangar entrances, ready to drop them in event of attack.

The Mighty Wind slowed as it entered the dark hangar, the grand walls ringing with sounds of the forge. Side vents halfway up Warsong Hold expel most of the noxious smoke from the furnaces, but the upper levels cannot completely escape the foulness. Smoke and the smell of burning metal hang heavy in the air, made worse by the stifling heat.

“Welcome to Warsong Hold!” yelled the captain as we came to a stop at a metal platform. A heroic scale statue of an orc glared down at us from the other side of the hangar, its granite jaw set in a scowl.

“Not very welcoming is it?” remarked Izzig Nomzob, an esteemed goblin engineer. One of the designers of Warsong Hold, he’d gone back to Orgrimmar to report on the performance of the fortress. He’d told me a great deal about Warsong Hold on the way north. Conversation is the only entertainment option aboard the bare-bones northbound zeppelins.

“I should say not. Who is it supposed to represent?” I asked.

“That’s actually an interesting story,” he replied as he picked up a pair of steamer trunks. “I’ve met the sculptor, a passionate if somewhat thoughtless orc named Merkut. He wanted to make a big statue of Thrall, since he was so fond of the Warchief.”

“It does not look like Thrall.”

“Because it isn’t. The Warchief sent Merkut a really nice message saying that he didn’t think making an epic statue was a good use of resources. Merkut threw a tantrum for the ages. Then Garrosh told Merkut to go for it, so Merkut did, taking over a whole peon work crew.”

“But he didn’t make the statue to portray Thrall.”

“Right, Merkut was insulted. So he made a statue of some nameless orc who just happens to look like Garrosh. I’ve heard the man talk, and he thinks it raises morale. Of course, that’s not how he put it; he said it reminds the orcs of the fury that is their birthright, or something.”

“Didn’t Thrall object when he found out?”

“Probably. But a lot of the people here like it. You know orcs, a lot of them will ascribe some deep meaning to any object that catches their fancy.”

I took another look at the glowering statue, suddenly appreciating exactly what Thrall had to deal with on a daily basis.

Our footsteps clattered on the metal stairs leading into the bowels of Warsong Hold. Izzig and I passed a mind-boggling number of armories, barracks, and workshops on the way. Torches and the odd electric lamp only accentuate the Hold’s grimy and barren appearance, so that the usual dimness is almost a relief. Banners of black and blood red drape across the walls, furthering the grim aesthetic.

Something in the size and scale of Warsong Hold serves to brutalize the individual. It is impossible to go through its sweltering stone halls, so much like warrens, and not feel somehow oppressed. Warsong Hold is more like a machine than a city.

Its imposing nature definitely gives Warsong Hold a psychological edge against attackers, though one wonders what for; the Scourge cannot feel fear. The obvious answer is that it is intended to intimidate the Alliance. Perhaps though, I should not make too much of Warsong Hold’s visual qualities. A fortress should look menacing, though Warsong Hold’s builders took this concept to a bold new level.

“Might be hard to believe, but Warsong Hold was really touch and go in its early days,” remarked Izzig.

“How do you mean?”

“Ah, I forgot, they didn’t want to advertise this down in Kalimdor. But there’s no law against me stating the facts now that it’s safe. The Scourge almost wiped the place out. First the kvaldir—basically vrykul pirates—knocked out the maritime supply lines. The Scourge took over the surrounding farmland, and then attacked from underground with those undead spider monsters they love so much.”

“How did Warsong Hold avoid getting starved out?”

“Airlifts helped; that’s why there’s a zeppelin line to this place. Also we’d sometimes be able to secure the supply routes for a month or so, long enough for a new shipment to get in. The place only really became stable a few months before Wrathgate.”

“What about Valiance Keep?”

“They’ve had problems too. Those kvaldir really did a number on the supply ships. Not so much any longer, though; the Alliance reinforced their merchant flotillas, and the kvaldir can’t do much against those.”

“How big is the Scourge presence now?”

“Hard to say. There are still a lot of nerubians in the quarry, though we’ve reduced them by a lot. Kvaldir keep raiding the coastline, but less than they used to.”

“These kvaldir are vrykul, you say?”

“I’ve never seen one, but I hear that they’re green and covered in barnacles, and are savagery incarnate! You know how orcs love exaggerating things, though,” he laughed. “No one knows where they came from; they probably woke up with the rest of the vrykul.”

“How secure is Warsong Hold now?”

“Better than it was, but that could change. At least now the peons know what they’re doing. Let me tell you, the Horde practically sabotaged Warsong Hold with bad peons for political reasons.”

“I don’t follow.”

“Well, it’s kind of complicated, but I’ll explain it as best I can. You said you went to Thrallmar, in Outland, correct?”

“I did.”

“And you noticed how the peons there were a lot more dedicated than usual?”

“Yes, admirably so. They were like the peons on the Kalimdor frontier.”

“Right. Some elements in the Horde—I won’t name names—didn’t like the idea of peons becoming confident or putting on airs. So the orcs gathered up the sorriest work crews they could find, mostly from the streets of Orgrimmar, and sent them to work here. The poor saps had no idea what they were doing. Nerubians killed them in droves, and they ran at the first sign of trouble.”

I sighed in disgust.

“I mean, they could have gotten those Thrallmar work crews, who know how to build and can take care of themselves in a fight. I guarantee you that if they’d done that, Warsong Hold wouldn’t have had half the trouble it went through. But the peons who survived got pretty good at what they did, or so I hear. I don’t talk with peons all that much in my job.”

“So the Horde hired incompetents to avoid creating independent-minded peons, and ended up doing just that.”

“You got it. Nothing like orcish politics, am I right?” he snickered, flashing a yellow-toothed grin.

I bade farewell to Izzig at one of the lower level foundries, the smelters and gears churning out the Horde’s war effort. Goblin workers hurry through the smog and noise, clad in iron masks and kodohide aprons. The din and heat reminded me of the Great Anvil in Ironforge, though not quite as impressive.

Goblin contractors have played an increasingly vital role in Horde affairs in recent years. Thrall’s Horde continues to lag behind the Alliance when it comes to technology. I have heard that the Warchief has attempted to persuade these contractors to form their own cartel, which would in essence create a new Horde nation (some of them already work for the rapacious Bilgewater Cartel). So far he has not had much success, though there’s little doubt that the Horde would fall to a second-rate power without goblin help of some kind.

A cramped drinking hall near the forge called the Blood of Heroes acts as a recreational area for guests. Exposed as it is to the ear-splitting ring of metal on metal, it almost seems designed to discourage long visitation. Barrels of bloodmead and other drinks are piled up against chain link fences. Tired-looking new arrivals slump at the squat tables that are too small for any of the Horde races to sit at comfortably.

Izzig had told me that visitors usually slept in the leaking storage rooms of the bottom floor. Though I’ve slept in much worse places, the idea of going down there so soon after my arrival struck me as most unappealing. I ordered a mug of ginger beer and sat down next to a young Mag’har warrior, sharp tribal emblems tattooed on his broad chest. He looked at me as if in appraisal, before speaking.

“Stranger, have you ever set foot in Garadar?” he asked, his stormy voice easily heard over the noise.

“I have. Did we meet?”

“Not face to face; I was still a whelp in those days. I recall you, however. Uh, I am honored that fate has brought us together yet again,” he said in a cautious voice.

“Thank you. My name is Destron Allicant.”

“I am Rohg, son of Skral’don.”

“Did you recently arrive from Outland?”

“Such has been my honor. Azeroth is an interesting place.” An almost comical smile broke out on his brutish features. “I am still amazed by Orgrimmar. Never in my life had I imagined so many orcs living together like that! I knew that the draenei could do such things, but the orcs? Never! Or so I thought.”

“Do you like Orgrimmar?”

“It is a strange place, but I think I do like it. My brother warriors say it makes its inhabitants soft. Maybe this is so. But the orcs on Azeroth, on a whole, are mightier than the Mag’har. Only a fool would think otherwise. Also, I cannot help but love a place where, if you are hungry, you just go down to the shop and buy a hunk of kodo meat!”

“City life does offer convenience.”

“And women! The green skin is strange, but I find it to my liking. So many of them too!”

I smiled. Rohg’s story reassured me. There are some in Orgrimmar who fear the Mag’har’s cultural impact on the Horde, warning that it will supplant the values presented by Thrall. Nor is this by any means an unreasonable concern; we are only seeing the beginnings of the Mag’har influence on the highest levels of orcish society, and it hints at dark times to come. However, such affairs never go only one way. Just as the Horde is changed by the Mag’har, so too are the Mag’har changed by the orcs.

I spent the night sleeping on a threadbare mat, in a pitch black room where streams of frigid water flow down the stone walls. The other guests and I agreed that it is still far more comfortable than the cramped and freezing zeppelin passenger compartments.

Waking up early, I spent the next morning exploring the tunnels of Warsong Hold. One needs to spend some time going through the citadel’s interior to truly appreciate its size. Dozens of stairways and torch-lit halls coil through the structure, depositing travelers in armories and forges, barracks and observation posts, all stacked on top of each other.

Getting lost is almost a certainty for the first-time visitor. Few of the rooms stand out, and the constant darkness makes it all the more disorienting. I could scale a near-endless stairway, and still find myself in the icy dampness that characterizes the lower levels. The clang of hammers on anvils echoes down the narrow corridors on some levels, and I would follow the sounds only to find myself at an empty storage room or lonely turret.

After passing by a half-empty storage room for what seemed like the fifth time, I decided to get help. I introduced myself to an off-duty peon, his left leg in a crude brace. He bowed with a smile, and said his name was Krug.

“How might I get back to the Blood of Heroes?” I asked.

“Hmm, you’re nowhere near it. That place is, let’s see, six floors down.”

“Down? I thought I was in the lower floors already.”

“No, you’re towards the top. This section’s drafty like you wouldn’t believe though, and it’s not directly over any furnaces.”

“How do you find your way around here?”

“Heh, it’s an acquired skill.”

“I’m sure you pick up a good number of those in a place like this. What sort of work do you do?”

“Whatever needs to be done. I end up in the quarry more often than not, but I’ve labored at other tasks. I work, as a peon must.” He said this with firm pride.

“I heard that the peons have become much more effective in recent months.”

“We just needed to realize our own strength. Out in the quarry, five months ago, a bunch of us took down a crypt lord. Have you ever seen one of those things? All squirming legs and pincers, as big as two kodo.”

“I have not. You killed it?”

“Not alone! Many brave orcs died there, but at the end of the day we won. We didn’t bother a single warrior either, we did it on our own.”

“You’ve every right to be proud. I’m surprised you weren’t made a warrior as a reward.”

“Why should I be singled out for reward? All of us did our part. Besides, we’re satisfied with what we’re doing. The strength of our arms and the fires in our souls keep the war effort going.”

I returned to the Blood of Heroes, impressed with Krug’s courage and determination. These traits are not often encouraged among the peons, and when they do, it is usually as a means to making them warriors.

In truth, Krug had done even more than I thought. Krug’s name seemed to be on everyone’s lips. “We work, as peons must,” had grown into a mantra, echoing up from the quarries and forges. Used to quelling the odd examples of peon rebellion, the warriors could only encourage this new type of dedicated laborer.

“Krug? He does not like to admit it, but everyone knows he delivered the killing blow!” said one peon in a conspiratorial tone.

“Why does he not admit it?”

“I do not know, but he puts the warrior’s fury in our souls!”

New peons are regularly shipped up to Warsong Hold, and present themselves in the same cringing way that most have come to expect. Such behavior is no longer tolerated. I visited a peon barracks and watched as a burly foreman, with scar tissue for a scalp, shouted at a pack of whimpering newcomers.

“Are you humans? Did your human mothers teach you to whine and beg?” barked the foreman.

“We are orcs!” shouted back one peon, braver than most. The foreman’s head swiveled to face the rebel, his eyes wide.

“You say you’re an orc? What’s your name?”

“Sturk.”

“Sturk? Well why don’t you act like an orc?”

“I am an orc—”

“Not yet! No orc would snivel like I’ve seen you wretches doing. If you want to live, you will learn to be an orc and a peon. We will work! Whatever it takes, we will work! If our blood turns to ice, we will work! If the Scourge swarms through these walls, slaughtering orcs left and right, we will work! Orcs do not let anything stop them!

“The Warchief has chosen us to bring war to Northrend! Our sweat will be traded for the blood of our enemies. The warriors of this citadel will be our masters, and we will stop at nothing to serve them. If I see any of you weaklings lazing off I’ll have your hides! The war effort depends on us! Never forget this!”

I left the peon barracks with a smile on my face. It is high time that the peons realized their own strength. In the past, peons who went above their station would be shunned. No peon, most orcs believed, had any right to act like a warrior.

Krug has found a way around that, by stressing the peon’s role as separate from (though still subordinate to) that of the warrior. His example has added a heroic quality to the backbreaking labor of the peons. Now they pursue their work with a very orcish intensity. In so doing, the quality of the work is immeasurably improved, as each peon competes to show off his own skill and strength in a manner akin to the dwarves.

However, I cannot let myself be too optimistic. I have long believed that the orcs need to cultivate a greater sense of individualism. Doubt and personal independence may lessen the likelihood of another Gul’dan deceiving the majority of the race. While the intensity of these peons is laudable, they still see themselves only useful in the context of a war effort. This creates disturbing implications for the rising tide of orcish militarism.

*********

A fog of dust and grit pervades the jagged pits around Warsong Hold, the result of the near-constant labor. I watched as peon work crews assaulted a nearby cliff face with picks and hammers. A few overseers stood on a nearby platform, trying and failing to look important.

Mightstone Quarry is almost as imposing as Warsong Hold itself, a wound in the stony earth that stretches for miles around the keep. Goblin blasting powder shattered the ancient landscape, which was then further shaped by peon hammers and picks. Warsong Hold’s planners saw the mineral-rich earth as sufficient cause to sacrifice the convenience of a coastal location. The fact that the supply lines are firmly in orcish hands has justified their decision.

The nerubians had turned Mightstone Quarry into a bloodbath. Deathless arachnids broke out from the cold ground in swarms, cutting down peon and warrior alike. They attacked with impunity, melting tunnels through solid stone to attack behind Horde lines.

I heard the story from a stern tauren shaman named Kolhowakan Windmane.

“We knew that it was only a matter of time before the nerubians destroyed the very foundations of this grim place,” he explained, each word coming out a sigh. Already old, the gray dust made him appear even more aged.

“What did you do?”

“All the shamans in Warsong Hold gathered at the top of the citadel. We sprinkled the surface with stone and dust and began our song, a dirge for this once beautiful land. We knew the spirits had every right to hate us.”

“Pardon me, but what did the United Tauren Tribes have to say about Warsong Hold? The construction methods seem to go against your values.”

“We were not asked. I should add, however, that we are not heavily invested in Northrend. It would not be proper for us to demand significant oversight. Nonetheless, we thought our friends would proceed with more caution. Perhaps we have not provided as good an example as we should have.”

“I see. Please continue.”

“I heard the voice of the earth in the rumble of stone, asking us why she had been hurt. We all fell to the ground, coating ourselves with dirt and begging forgiveness. Mercy only came because the world hates the Scourge more than it hated our trespass. The spirits of the earth accepted totems that would strengthen the foundations around Warsong Hold, protecting it from the corrosive spit of the nerubians.”

“Did it ask for anything in return?”

“When the Lich King is no more, we must stop all work in the northern half of Mightstone Quarry. We shall fill the pits with earth watered by our tears, and give it back to the world. No one but druids may live on it. There, the students of Cheyowattuck, whom you call Cenarius, shall return life to the heath.”

“They’re allowing us to keep the southern portion?”

“Yes, but not for all time. When they tell us to, our descendents must fill it up and make it bloom. Warsong Hold itself may stand as long as there are brave souls to defend it.”

I could tell from first seeing Warsong Hold that it had not been built with the spirits in mind. Shamanism has long been a Horde mainstay, helping it survive the difficult early years. Yet dealing with the spirits means that one must reciprocate their favors. Exactly how this will affect Horde strategy remains to be seen.

Having explored Warsong Hold as thoroughly as possible, I had set my sights on Valiance Keep. To get there, I would have to cross the unearthly Bloodspore Plains that stretch to the east and north of Warsong Hold. My guide through the Bloodspore Plains was a Forsaken alchemist—unaffiliated with the Apothecarium—named Vilus Henelvy.

Some Forsaken come through death with only a few physical scars; Vilus seemed to be nothing else. Short and stocky, scar tissue had distorted his face into a frightening blank, marked only by a slit-thin mouth and pinprick sockets. Splayed and green hands hung at the ends of his stumpy arms, some of them bound in metal wire. His sense of aesthetics matched his wounds, a mishmash of furs and hides sometimes stitched onto his body.

“Good morning, Destron! Are you ready to explore the wonders of the north?” he greeted me. Wounds in his mouth made speech difficult, but there was no hiding his oddly compelling enthusiasm. Vilus was a man who loved his work.

“I’m more than ready. Thank you again for letting me tag along.”

“Of course! As much as I love the Bloodspore Plains, there’s no denying that it’s a very dangerous place. Most of the orcs here say they’re too busy to join me, and I wouldn’t be so foolish as to turn down help!”

“If you don’t mind my asking, how did you fare in Warsong Hold after the Wrathgate Massacre? I am not sure that everyone here would bother to distinguish a regular Forsaken alchemist from the apothecaries responsible for the crime.”

“Ah, yes, unfortunate incident, that. They threw me in a cell and rifled through all my notes—made a terrible mess, they did! I was let out once things cleared up.”

“Have you ever done any work with the Apothecarium?”

“I took advantage of their resources early on, but our interests did not coincide. They want to develop plagues, I just want to learn about the world itself. The compositions of herbs and chemicals fascinate me, and I find it helpful to ruminate on them in my newfound quasi-immortality.”

“That sounds reasonable. There are other branches of the Apothecarium that are more interested in such things.”

“Perhaps. I do not like having to work with others, however. It only slows me down.”

“They do offer resources,” I pointed out.

“True. For the moment, I have enough. My father was a very wealthy man. Though undead, I was still the legal recipient of his fortune, and was able to reclaim it from the ruins of his estate.”

Vilus soon launched into a lecture, perhaps better described as a barrage, of alchemical and environmental information. His knowledge on the subject was profound (if sometimes myopic), and I regret being unable to take notes as I walked.

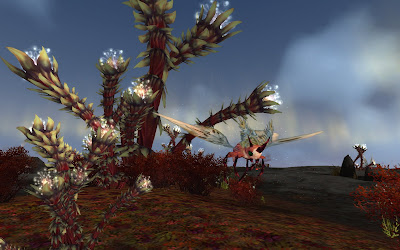

The blade-topped steel gates of Mightstone Quarry open up to vast domain of scarlet moss, forming a living carpet on the miles of jagged rock that extends to the horizon. Frail blossoms spread petals of translucent red and white, overshadowed by the eponymous bloodspore tendrils that grow in groups of two or three, reaching lengths of up to nine feet. Thick and fleshy blades the color of dried blood protect the bloodspore’s fragile stalk. When the bloodspores bloom, the plate-like petals turn white and tufts of silvery filaments, almost like dandelions, start growing from the tips.

These strange plants, unique to the Borean Tundra, grow in profusions along the mossy plains. Veritable forests of them stand around the limpid pools dotting the red land under the lights of the northern sky, creating a vista as alien and beautiful as anything one might find in Outland.

“An amazing place. Are you the only one to study it?” I was sure that the tauren, at the very least, would seek to learn about the spirits of the Bloodspore Plains.

“No, there were some blood elves doing research as well. Their research was more militaristic in nature, and as much as it irks me to do so, I must concede that they made more breakthroughs than did I. Fortunately, there’s still plenty more to study.”

“Militaristic?”

“Oh, you know, they wanted to find ways to defeat the magnataurs and the snobolds.”

One of the orcs in Warsong Hold had mentioned the magnataur and snobold presence, though he stated that their leader had recently been slain.

“What do you hope to find?”

“First, I’ll explain what we do know about the bloodspores. The pollen from their flowers is carried by giant moths native to this region. Now, when a pollinated bloodspore flower is ground up, it exudes chemicals that weaken and confuse most races, the magnataurs most of all. This is how the magnataur leader, Gammothra, was defeated. Snobolds, on the other hand, appear to be immune.”

“Then why would magnataurs live here?”

“A good question! It is entirely possible that they do not realize the effect; magnataurs are not known for intelligence, after all. Or, it may be for some other reason entirely. I want to find some pollinated bloodspore flowers to take back for study.”

“Seems like it would be easy enough.”

“I hope so. The snobolds protect the bloodspores and the moths, but they’ve been in disarray ever since Gammothra’s death. We should be able to take advantage of that, and avoid fighting anyone.”

I watched and listened as Vilus roamed around the Bloodspore Plains, stopping to harvest samples of plant life and place them in a tin kit. Life abounds throughout the plains, most notably in the giant moths that hover around flowering bloodspore tendrils. Most native fauna is small, consisting of rodents and tiny birds.

Vilus told me about his past, particularly of his days in Gnomeregan. The Royal Alchemical Society of Lordaeron had sent him to the fallen gnomish city as part of an exchange program, and he spoke of the place with real wistfulness.

“Granted, everything was a few sizes too small for me, but the resources they had there were incredible! I hope this doesn’t make me a bad Horde citizen, but I do want them to get their city back. A revitalized Gnomeregan would be of immeasurable value to progress. You know, the gnomes were the only Alliance nation that considered recognizing the Forsaken as the successors to Lordaeron.”

“I did not know that.”

“It’s true! Hiltrip Beakerflare himself told me, in the Alchemical Convention at Booty Bay two years ago. Gnomeregan’s government in exile still opposed us, but there were some who vouched in our favor. They thought we could give them more information about undeath. But our supporters were overruled, largely due to the Dark Lady’s murder of Garithos. Oh well.”

We found the snobolds early on the second day. Little was known about the snobolds, though they appear functionally identical to the rat-like kobolds found in southern lands. No one has conducted extensive observation of the snobolds. What has been seen of them suggests that they trap large game animals in the southern steppes, and guide their magnataur masters to the helpless prey.

“A bit like hunting dogs, though with opposable thumbs,” said Vilus, by way of explanation.

No one knows how long the snobolds have served the magnataurs. There was a time when all of Northrend suffered under magnataur brutality, lasting until the Northern Concord, a coalition of humans, taunka, tuskarr, and some wolvar, forever broke their power. As no snobolds were recorded during the Northern Concord’s campaign, it is believed that they only recently fell under magnataur domination.

There is no doubt that the magnataurs are a culture in steep decline. Already a shell of their former power before the Scourge, the rise of the Lich King has weakened them further. For all their size and ferocity, they rarely hunt, preferring to rely on the snobolds’ trapping expertise.

“A typical magnataur herd is a bit like a lion pride. It consists of a small retinue of males who spend their time eating and sleeping, interrupted by the occasional squabble over seniority. The females go out to collect the food that the snobolds trapped for them.”

“Are fewer males born than females?” I asked.

“Hard to say. No one’s done any serious studies on the magnataurs, except maybe the nerubians, and no one can access their writings. It could be that there’s a similar birth rate for both sexes, and the males just frequently kill each other.”

“The leader of the local herd has been killed, correct?”

“Yes, and now the magnataurs are scattered. But the snobolds still seem to thrive.”

The snobolds of the Bloodspore Plains congregate around natural monoliths. They decorate the stones with all manner of found objects: bones, hides, bloodspores, and discarded weapons among others. Coal, gathered from surface deposits, is placed in bowls and set alight around the monoliths, so that each one is surrounded by a cloud of black smoke. Some snobolds strap these bowls onto their own heads.

Hidden in a copse of bloodspores, we watched as the snobolds scurried around one of the monoliths, waving burning sticks and emitting hoarse shrieks and cries. The pale morning light gave the scene a decidedly dreamlike atmosphere, and I almost felt as if I were looking back in time. I could not determine any organization; no snobolds stood out as leaders. Their spindly bodies shivered and twitched, as if racked by convulsions.

Hours passed as we observed in silence. I wondered if we were observing a snobold shamanistic ritual, though I saw no visible signs of a spiritual presence. A pack of five snobolds ran up to the monolith at around noon, their claw-like hands gripping bloodspore flowers the size of their heads.

They passed the flowers on to the snobolds with bowls on their scalps, who put the flower in a crude mortar and pestle. From my vantage point, I could see them crushing the blossom into a fine red paste. Then, they emptied the mortars into the charcoal burners.

Vilus nudged me, holding his hands over his mouth and nose for emphasis. I did the same as the bloodspore smoke rose into the sky, the shrill cries reaching a crescendo. Snobolds ran in circles around the monolith, cavorting like men possessed.

A distant rumbling heralded the approach of something massive. I pressed myself deeper into the red moss as the shaking grew worse. Snobolds shrieked in fear or glee, clustering at the edge of a rugged slope. We saw the magnataur’s head first, a brutish parody of an ape’s. Two yellowed tusks hung from its lipless mouth, each twice the height of a man. The rest of the body soon quaked into sight, a mountain of muscle wrapped up in sagging blue skin and coarse white fur.

Looking at it, I could easily see why the magnataurs had ruled Northrend for so long. An armored knight would be crushed by a single blow from one of its loping arms. Black stains spotted its rough pelt, the remnants of meals long past.

Yet for all its strength, the magnataur could only drag its feet towards the chittering snobolds. Its head was bowed, and it swayed like a drunk. I wanted to ask Vilus if the flower’s smoke had addled the magnataur, but stayed silent for fear of detection.

One snobold, wearing a smoky bowl as his crown, screeched over the rest. In a rapid fusillade of squeaks and chirps it gestured to the plains below, while the other snobolds made wild genuflections before the magnataur. The exchange lasted no more than a few minutes. The lead snobold dropped his arms and went silent as the magnataur turned around, stomping back down the ridge.

The snobolds stayed at the monolith throughout the day, tending the flames. A cold northern dusk was falling upon the land when the magnataur returned, its massive arms cradling the bloody corpse of a woolly rhino. Ear-piercing cheers went up from the snobolds, who spread in a circle around the returned hunter. A few went to add more bloodspore to the fires. Exhaustion was evident on the magnataur’s frame, the wide chest heaving as it tried to get more air.

It dropped the corpse a moment later and the snobolds swarmed it like rabid dogs. A few of the bigger snobolds jumped into the fray and pushed their smaller brethren aside, imposing a crude order on the affair. Through this the magnataur watched without reaction, barely able to stand up under its own strength.

Finally, the lead snobold yelped something to the magnataur before leaping off of the rhino with its fellows. Grunting loudly enough to shake the stones beneath, the magnataur reached into its belt and took out a sharpened stone. Lowering itself over the dead rhino it began to cut at one of the hind legs, opening up a jagged tear along the side. Upon loosening it, the magnataur tore the leg off with a single terrible pull and instantly set about devouring it.

As the magnataur devoured its portion, the snobolds began to divide the prey amongst themselves, their greedy hands cutting out chunks of flesh that they held fast to their chests. A few of them used looted Horde weapons for the butchery, though most made do with stone tools.

Within an hour they’d stripped down most of the rhino carcass. Each took at least two servings of flesh, and many shoved a third into hide pouches for a future meal. The lead snobold barked again, and the magnataur lowered itself onto the remnants to gorge on whatever it could find. The last snobolds extinguished the fires before leaving, plunging the area into darkness. Vilus and I made our escape at this time.

“Amazing!” he exclaimed, once we’d reached a safe distance. “I only wish I knew more; this brings up a myriad other questions.”

“What was your interpretation?”

“From the looks of it, the snobolds are using the pollinated bloodspore flowers to control the magnataurs. What we really need now is a linguist to decipher their language, damn, don’t know where I’ll find that. Getting back to the topic, I am pretty sure that the snobolds are now ordering the magnataurs to fetch food.”

“But why would they need the magnataurs to do that? Don’t the snobolds trap their prey?”

“They do, but there are other predators on the steppes, like wolves, that will quickly eat the trapped animal. Traditionally, the magnataurs have been able to scare the wolves away from the prize.”

“They must work very quickly on that case.”

“We’ve seen snobolds using signal fires to spread word. I can’t imagine it’s foolproof, especially with the magnataur’s slowed reactions, but it probably works often enough. Think about it, Destron. This explains why the magnataurs live here. The snobolds figured out the secret of the bloodspores, and use it to exploit the magnataurs.”

“So the magnataurs were never in control.”

“Maybe. This might be a recent development. More research still needs to be done on the matter. Now, we observed that the snobolds let the magnataur take the first cut; this might be done out of respect, or simply out of habit if this was not always the norm. At any rate, the relationship is not entirely exploitative.”

“The magnataur hardly seemed to be in good health,” I argued.

“True. But she did get the first pick. Like I said, more research needs to be done. Anyway, this is groundbreaking. Everyone’s always assumed that the magnataurs controlled the snobolds. Now, we know that those clever snobolds can turn the tables, at least here.”

Though curious to learn more, I knew I could not stay and wait for more research. I bade farewell to Vilus early the next day, wishing him luck in his efforts.

*********

I crossed the beach at low tide, my feet sinking into the cold gray sand. Barricades and the burned husks of twice-killed nerubians are strewn across the rocky strand, slowly eroding under the tide and wind. Valiance Keep stands in precarious triumph over this lonely scene, its white parapets built on the briny islets beyond the shoreline. Cannons peek out like metal eyes between battlements and through windows, a testament to Alliance vigilance. A narrow channel of seawater cuts through the settlement, occupied at the time by an eagle-prowed icebreaker.

Fear mixed with my curiosity. I wondered if my disguise was really so effective. Would not security be higher after Wrathgate? Still, there was no reason they would think me anything other than a human. Valiance Keep sees a heavy traffic of individuals and material leaving or arriving at Northrend. One more face, I reasoned, would not make any difference.

Sure enough, the guards shooed me in without a fuss. The vast courtyard of Valiance Keep is a scene of endless commotion taking place in a forest of cranes and scaffolds. Dozens of laborers work at constructing new towers and barracks, supplied by porters who push heavy carts across the stone pavement, forever slippery with the sea spray. They even used the docked icebreaker (which was being repaired) as a makeshift thoroughfare. A solid keep watches over the proceedings.

“Make way!” bellowed a young Stormwinder as he pushed a wheelbarrow filled to the rim with wooden beams. Stone is the preferred building material in Valiance Keep, though some lumber is imported from Stormwind and southern Lordaeron.

Not sure where to go, I impulsively crossed the icebreaker to the other side of Valiance Keep. There, the humans have made some attempt to create a homely atmosphere. Stunted hedges grow in planters along the waterline, and small flowers bloom under the window sills. Peak-roofed houses, similar to the ones in Valgarde, offer shelter from the bitter cold.

The Old Mountain Home is Valiance Keep’s inn. As the name suggests, the interior is designed to look like a Stormwind mountain lodge. The bare wooden walls are covered by tapestries that are embroidered with trees and flowering vines, a contrast to the Borean Tundra’s stark beauty. Hunting trophies line the wall, and a grand stone fireplace fills the parlor with an intoxicating warmth.

I met a draenic Vindicator named Weleeda, who’d recently arrived from Exodar. It was her first time living with humans, and she was more than happy to talk about Valiance Keep, a smile gracing her luminous features.

“We have all been very impressed by how well Valiance Keep has stood up to the rigors of the north. Regrettably, I could not take part in the initial founding, but the inhabitants of this citadel demonstrated admirable bravery and cooperation.”

“What were some of the difficulties faced by the founders?”

“The Scourge, naturally. Unnaturally, perhaps! That entire stretch of beach was infested with nerubians. A few were even able to undermine portions of the walls, causing significant damage. The colony of Farshire was almost completely overrun.”

Very similar, I thought, to Warsong Hold’s situation.

“The nerubians are gone now?”

“There are still some pockets of resistance in Farshire, which we are working to eliminate. Sadly, there is no way to reason with the Scourge.”

“Please do not take offense, but I’ve seen very few draenei in Northrend. May I ask why?”

“Why would I be offended?” She looked genuinely curious.

“Well, some might interpret the question as implicating cowardice or apathy on the part of the draenei,” I answered, somewhat awkwardly.

“Really? How curious! That is a human reaction?”

“For some humans. I only asked to make sure.”

“I see. At any rate, my people are currently of limited means. So few of us survived the Burning Legion’s depredations. We did invest a significant number of troops in Outland, so as to stem the demonic tide in our old home. However, we came dangerously close to overextending ourselves.

“Thousands of draenei perished in the Outland campaign and in Quel’danas, forcing us to consolidate. Most of our involvement consists of sending support troops and various experts.”

“Such as yourself.”

“I am actually part of the limited military presence. High Vindicator Dolun was concerned that the faith of the draenic soldiers in Valiance Keep was weakening due to the isolation.”

“Do you think his concern was valid?”

“He would not send us here if it were not. The interaction with humans has been a significant interest. Initially, the draenei were sequestered from the main force. Our resemblance to the Eredar demons was very disturbing to the humans. Their caution was misguided, though it displayed a commendable wariness.”

“But you are now integrated?”

“Correct. Interaction in Outland tended to be limited, so this has been a fine learning experience. Most of the soldiers here are from a place called the Redridge Mountains.”

“Ah, I’ve been there! That explains the decor in this inn.”

“I do know that some of the humans here are unhappy; they believe that Stormwind has neglected the Redridge region. But the peril of our situation has forged a strong camaraderie.”

I immediately knew I had to learn more. As King Varian languished in Horde captivity (yet another mark of shame in my faction’s history), Stormwind fell into chaos. In Redridge, this took the form of a full-scale attack from the Dark Horde’s remnants.

I spent the night in a barracks-style structure adjoining the Old Mountain Home. The inn is almost always filled to capacity, forcing them to use an overflow room. I met some of the other visitors to Valiance Keep, a collection of treasure hunters and sell-swords. A substantial portion of them were veterans of the Outland campaign, ready to go wherever there was action.

“I already burned through most of the coin I earned in Outland, so Northrend seemed the next best place,” remarked Darresias, a Lordaeronian mercenary. He took on an oddly foppish demeanor, wearing a carefully maintained pencil-thin moustache of the type currently in vogue among Stormwind’s nobility. The left side of his head, with its livid scars and missing ear, proved he was no mere dandy.

“Where in Northrend do you intend to go?”

“Seems as if I’ve missed the fun here in the Borean Tundra. I’ll be headed north, to the thick of things. Lake Wintergrasp most likely, but who knows? Perhaps fortune has something else in store for me.”

A fierce storm lashed the keep that night, the crash of thunder punctuating the sounds of the wind and the waves. Sleet fell in torrents, covering the ground in half-melted ice. Despite this, the people of Valiance Keep roused themselves to another day of labor at first light, shivering in their thick great coats. Workers rubbed calloused hands together for warmth, sometimes heating them with foggy breaths.

Progress had paused on a half-built warehouse, the laborers waiting for the foreman to arrive. They clustered around a small cauldron of boiling tea, ladling it out into battered tin drinking cups. I talked to one of these workers, a man named Orlan.

“I’d like to claim some land up here, but they only allow you to do that if you volunteer for work in Farshire,” he said.

“Why is that?”

“Farshire turned into a spidery and cult-ridden hell on earth a few months back, and it’s still far from safe. They know it’s a miserable place, so that’s why they forced any would-be landowners to spend some time there. Personally, I think the nobles are hoping we’ll all get killed off so that they can claim the land!”

“Don’t you get compensation for being in Valiance Keep?”

“I do, and good compensation at that. But they told us there would be plenty of opportunities for land. Turns out, once we get here, all those opportunities involve Farshire.”

“Is Farshire still so dangerous?”

“Not as much, but I’d really rather not go there. I’ve heard the Cult of the Damned is still active. They found some cultists in Valiance Keep too, a few months back. The ones who were caught were killed, but who knows if we got them all?”

While Valiance Keep’s soldiers hail from Redridge, the colonists are drawn from the ranks of the poor or ambitious in Stormwind City and Elwynn. Most are more enthusiastic than Orlan, though some wonder why they couldn’t just colonize the still-undeveloped regions of eastern Redridge, or reclaim Westfall’s miles of abandoned farmland.

Stormwind’s colonization efforts seem to consistently run into unexpected barriers. In the Howling Fjord, the vrykul threat keeps the colonists in their base camps. The question of Stormwinder versus native human land rights poses another issue. Those in the Borean Tundra must first secure Farshire, a task even more difficult than it first seems.

“It’s different when the Cult of the Damned is involved,” said Tenny, a hollow-eyed woman with limp blonde hair. She worked listlessly as a seamstress, her bony hands looking too stiff for the job. “Scourge minions just kill you. Usually your neighbors can burn your body or something, so you don’t come back. But the cult? They’ll raise you on the spot. I was in Farshire, I know! I saw it happen to my husband... no land’s worth that.”

Tears spilled from her eyes in a flood, and she gritted her yellow teeth. I did my best to comfort her and she nodded in response before returning to her work, crying in silence.

Stormwind’s colonists are a brave and hardy breed. Yet even the bravest might have second thoughts of going up against the cult’s necromancers, who are experts at swiftly bringing the dead to a state of horrific unlife. As a necromancer’s victim, I can sympathize with the colonists’ fear.

Until recently, most authorities believed that the Cult of the Damned was all but defunct. The Scourge relied on the cult to attract followers during its early days. Since then, it was thought they had been mostly subsumed into the undead ranks. The invasion of Northrend revealed that thousands of living cultists are still active.

No one is entirely sure as to why the Scourge keeps them alive; a necromancer can still operate while undead. Some suspect that the Lich King intends to cultivate a captive human population so as to have a regular source of new troops. Given the cult’s relatively small size, however, it will be some time before this becomes feasible.

Orlan had spoken about cult infiltration in Valiance Keep as if it were common knowledge, but most simply gave me odd looks when I asked about it. More than a few scoffed at the idea, and told me that such foolish talk would get me in trouble. Given the general state of anxiety, and Orlan’s own resentment, it may well be nothing more than a rumor. No one, however, denied the cult presence in Farshire.

My past deeds caught up with me at around sundown when an off-duty soldier ran up to say hello, a broad smile on his rugged features. He remembered me from when I had stood alongside the Returners, the militia of the Redridge Mountains, as they battled and ultimately repelled a small army of orcish renegades. As one of the only magic users in the area, my contribution had not been insignificant.

The soldier introduced himself as Parnour, and insisted on getting me a drink at the mess hall. I followed him to low-lying wooden building next to the barracks. He entered first, and I heard him call out:

“You won’t believe who I found! It’s Talus!”

Parnour popped back out a second later, pulling me inside with a grin. Two dozen cheers resounded through the hall on my entry, soldiers’ faces beaming all around the grimy table.

“Is it really you? By the Light! We weren’t sure if you still lived!”

“Good to have you back, Talus!”

“Maybe you’ll stay around a bit longer this time!”

For a moment I stood open-mouthed, amazed at my reception. Though I knew Lakeshire still remembered me, I never thought the Returners would be so enthusiastic to see me again. As someone who prefers a degree of anonymity, I found the experience both thrilling and discomfiting. Did they expect anything from me? Or were they simply voicing appreciation?

The cook, also a Lakeshire native, sat me down at the table and put a mug of lager in front of me, clapping me on the back as he did.

“A hero’s welcome, courtesy of the Returners!” he said.

The desolate mess hall soon came alive with lively conversation. I answered their queries as best I could, not sure how to react. Some asked what I had done after Lakeshire, to which I gave selectively edited accounts of my travels. I became unreasonably fearful of revealing my true identity.

As soldiers, they only had so much time to spend talking with strangers. Many had to go for evening shifts on the battlements, shaking hands with me as they left. The crowd thinned, and I found myself talking to a man named Nerrin. I’d met him before, though he’d been little more than a child at the time. Raised on tales of his grandfather’s military exploits, Nerrin had gotten his first taste of combat in the Battle of Lakeshire.

“How did Lakeshire fare after that battle?” I asked him.

“The Blackrock Clan kept up the assault, but they never again made an attack of that magnitude. Still, times were hard. The Returners had their hand fulls with the constant orcish scouting parties and probe attacks.”

“I remember that you sent messengers to Stormwind City, asking for assistance. Did the army ever come to your aid?”

“No. They said that the orcs were not enough of a threat. Merely brigands, they said, easily handled with a competent militia. They were right on one account at least; we held the line. I killed six Blackrock warriors with my crossbow, and I was far from the best fighter.

“We could never spare enough troops to attack the Blackrock bases all around Lakeshire. Volunteers like yourself came to our aid, clearing the orcs from Stonewatch Keep and other spots. After a while, the region was almost free.”

“Judging from your tone of voice, I gather this was not the end.”

“Do you know of Morgan’s Vigil?”

“Yes, I’ve been there.” Morgan’s Vigil is an isolated Stormwinder base in the Burning Steppes, north of the Redridge Mountains.

“A messenger came from there one night. The soldiers at Morgan’s Vigil had captured a Blackrock warrior and interrogated him. The orc claimed that his master, Rend Blackhand, was training an army of dragons. First he would destroy the Dark Iron dwarves, then he would burn Lakeshire to the ground. The people at Morgan’s Vigil thought it a mere lie at first, but they saw the dragons flying around Blackrock Mountain a week later.”

“What happened?” I actually knew full well what happened, but I feigned ignorance.

“Rend was killed. Warriors of Thrall’s Horde infiltrated Blackrock Mountain and slew Rend in his keep. The dragon army fell apart afterwards, saving Lakeshire from certain destruction. We held a celebration that lasted a full week, and we all felt like we’d been given a chance to start anew.

“I was an adult by then, looking forward to a quiet life. I’d seen enough bloodshed. My grandfather had passed away, and I inherited his carpentry shop. I was ready to marry my sweetheart and raise the next generation of Lakeshiremen. Then our king returned from captivity, calling us to serve the crown.”

“You volunteered?”

“I never had to. Stormwind law states that local militias may be conscripted in time of need. Since our king needed us, every Returner under the age of 35 went north to defend Stormwind in this cold land. It’s been a bloody campaign. However, just as the throne protects its subjects, so too must we protect the throne.”

Nerrin said this with a confident smile, but his eyes spoke volumes.