I was a few days' worth of travel north of Menethil and I had no other option than to dutifully begin walking. Great armies fought fierce battles through northern Khaz Modan in the Second War. Unlike Lordaeron, the orcs occupied most of the ancient dwarven continent for the duration of the conflict. The bloody campaign in the Wetlands took countless lives, and remnants of entire armies sank beneath the muck. Shortly before I died, I heard a dwarven veteran of the Second War saying that if the Scourge necromancers ever made their way to the Wetlands, they’d be able to raise legions from the marsh.

I made reasonably good time staying to the beaches. A nearly constant drizzle fell from the gloomy skies and I could just sense the smell of rain combined with the briny air. On occasion I passed the crude villages of the murlocs, their guttural croaks a primitive orchestra in the coastal mist.

I was a few days' worth of travel north of Menethil and I had no other option than to dutifully begin walking. Great armies fought fierce battles through northern Khaz Modan in the Second War. Unlike Lordaeron, the orcs occupied most of the ancient dwarven continent for the duration of the conflict. The bloody campaign in the Wetlands took countless lives, and remnants of entire armies sank beneath the muck. Shortly before I died, I heard a dwarven veteran of the Second War saying that if the Scourge necromancers ever made their way to the Wetlands, they’d be able to raise legions from the marsh.

I made reasonably good time staying to the beaches. A nearly constant drizzle fell from the gloomy skies and I could just sense the smell of rain combined with the briny air. On occasion I passed the crude villages of the murlocs, their guttural croaks a primitive orchestra in the coastal mist.

The murlocs are perhaps the most hated monsters in the world. These bizarre fish-men first appeared a few years before the Third War and the ensuing chaos allowed them to spread with ease. They present a continuing problem to nearly all coastal regions. No communication with them has succeeded, and they attack all who dare to venture close.

Menethil Harbor is a recent creation, having been built shortly after the Second War.

The murlocs are perhaps the most hated monsters in the world. These bizarre fish-men first appeared a few years before the Third War and the ensuing chaos allowed them to spread with ease. They present a continuing problem to nearly all coastal regions. No communication with them has succeeded, and they attack all who dare to venture close.

Menethil Harbor is a recent creation, having been built shortly after the Second War. Though the vast coastline of the Wetlands is an excellent spot for a city, the dwarves scarcely touched the place. The only previous habitation lay in the dreary fishing villages inhabited by dwarven pariahs. Those settlements were all destroyed or abandoned in the Second War. The armies of Lordaeron, who sacrificed so much to purge Khaz Modan of the orcs, were granted permission to build a new city in the Wetlands on very favorable terms.

Menethil Harbor, named after the late king, became a bustling seaport, trading with Southshore, Moonbrook, and places even more distant. Though under the jurisdiction of Lordaeron, a good number of dwarves lived in the city, their craftsmanship and work ethic being welcome additions to the burgeoning town.

Today, the walls of Menethil Harbor scarcely contain the city within, its gabled roofs and turrets tumbling over the edges like an overflowing cup. A briny wind swept over the coastal plain around the city as I approached. I saw the tall masts of ships on the horizon, going to and from destinations unknown.

I got into the city without trouble, the traffic too heavy for the guards to take notice of what they thought was a particularly sickly human. Seagulls wheeled in the gray sky above, their lonesome cries only occasionally rising above the noise of the crowd. The streets are narrow and winding, filled with fearful townspeople and swaggering mariners.

“A pretty bauble for the missus, perhaps?” came a cracked voice.

I looked down to see that what I mistook for a pile of grimy rags was actually an old woman, her left eye milky white and her exposed right hand covered in horrific burns. She smiled with a mouthful of gray and rotting teeth and held a globe of dusty glass in her good hand.

“Would a charm be more to her liking? Or some other trinket? I’ve got plenty, nothing more expensive than five coppers.”

I hesitated as she turned her remaining eye on me, possessed of the too-focused glare of the slightly mad.

“I’ll take that bauble.” I paid her a silver piece.

“Thank you, good sir! It’s good to know that some people have not forgotten their neighbors. The wicked people of this town treat me like they would an orc, though I’m from Lordaeron, just the same as they!” she hissed.

“You are a refugee?”

“Yes. I was once the loveliest creature that ever walked Brill and all the men there told me so! I married a handsome young soldier, strapping and brave, and had two wonderful sons. Then my husband, Willim, fell to the dead and came back, and my two sons did not long survive him. Now I am left alone, a pitiful old woman with scarcely a friend in this dark world!”

“I’m from Lordaeron as well.”

“You talk like one who is. What’s your name?”

“Talus.”

“I’m Weldana. Everyone came here trying to get to Stormwind, and people did at first. Then it stopped, and we have to make our way on these streets. I find these trinkets in the forgotten alleys of Menethil, abandoned by those who have no use for them,” she snarled.

For the first time I noticed beggars lining the streets, many sporting gruesome wounds. Foul-smelling tents filled the alleys and gutters, the homes of desperate rag-pickers and junkmen.

“I’ve made quite a lot today, thanks to you good sir. Light bless you Talus, you’re a better man than this entire town. Do you hear my words you city of the damned! Scourge take you all!”

Getting up, she conjured a walking stick from the folds of her rags and took a few tottering steps.

“I’m going to get myself a drink, I’m an old woman and I’m tired,” she sighed.

“Your generosity will always be remembered, sir Talus.”

“It was the least I could do,” I said, feeling horribly inadequate.

Weldana stopped, taking note of an emaciated beggar who lay in the gutter muttering to himself. He protectively clutched a bowl in his almost skeletal hand, a few miserable coppers lying inside. Weldana smiled and struck the man’s hand with her stick. He dropped the bowl, whimpering and talking incoherently. With a suddenness that belied her age she grabbed the bowl and seized the coppers. The bowl she then placed in her pack.

“What was that?” I demanded.

“He’s dead anyway, I need it more than he did.”

“I gave you a silver piece, and you repay my generosity by robbing him?”

“Give him some silver then, if you’re so damn generous! Don’t you judge me, you haven’t seen the horrors I have!” she screeched, her aged face contorted with rage.

She stalked off. I went to the beggar, who had crawled into an alley behind a pile of rubbish, a weird sing-song chant the only sign of his presence. He shrank back as I approached, his face more animal than human. He was completely mad and there was nothing I could do. Not expecting it to do any good, I gave him three silver pieces and a hunk of bread that I was carrying. The beggar scooped up the silver but left the bread, staring at it like it was some strange animal.

I encountered fewer beggars once I got past the gate area. I wondered if this was what happened to peasants who had fled through Southshore. Weldana mentioned being unable to reach Stormwind, not the first time I’d heard of such a problem.

There are occasional patches of greenery in Menethil Harbor, a particularly sizable one located near the docks. The city was meant as a showcase of Alliance wealth and ingenuity. The trees and grass are remnants of that failed and noble plan.

I was surprised to see a group of violet-skinned night elves walking down the piers, having just disembarked from a large freighter. It was the first time I had ever actually seen night elves. In addition to the difference in skin color they generally appear more robust than their high elven cousins. They kept close together, speaking in the fluid Darnassian tongue.

“I just got here from the north, do ships from Kalimdor come here often?” I asked a dock worker.

“I wouldn’t say often, but they come regular,” he answered.

“Odd bunch, though I have to say they’re easier than the high elves. I’m not saying the high elves didn’t do a lot for us back in the war, just that they aren’t the most agreeable sort.”

His is a common sentiment among the humans. The elves did not lend their soldiers to the Alliance until the enchanted forests of Quel’thalas came under attack by the orcs and trolls. They then had the gall to complain about the damage done to their forests, which could have probably been prevented if they’d helped out earlier. They seceded from the Alliance soon after the Second War. High elves were not well regarded after that, and some of the more callous humans regard the annihilation of Quel’thalas as a sort of poetic justice. The night elves are perhaps still too much of a novelty for any serious prejudice to arise.

Smoke and raucous laughter clogged the interior of the Deepwater Inn. A large fire blazed away in the hearth, casting flickering shadows in the parlor room. Straining to be heard above the din, a pair of musicians sang a shanty about a bloody fight on the high seas, playing on a concertina and a fiddle.

The Deepwater Inn is a rambling establishment known for its shady clientele and powerful grog.

I sat down at a filth-blackened table, the wood unpleasantly damp. The table was slightly askew, the result of it resting on water-warped floorboards. Exhausted serving maids walked in the narrow passes between tables, enduring insults and cat calls. A drunken wretch at the table next to mine held out his leg, tripping a hapless server. The mugs of grog she carried fell to the ground and a chorus of whistles rose from the inebriated mob. She slowly got to her feet and returned to the kitchen, not saying a word. Moments later she returned with another bunch of drinks. She passed by me and I saw the glint of blood on her lip.

I went up to my room as soon as I could only to find the bed already occupied by a ragged old man deep in drunken slumber. I didn’t have the heart to throw him out. Standing in the suffocating darkness of the bedchamber, the only sound being the drunk's wet snores, I felt a vague disappointment. Perhaps part of me expected more in lands where humans and dwarves still held sway.

*********

The next morning dawned gray and gloomy, a thick seaborne fog blanketing the streets of Menethil Harbor. The parlor was practically empty when I ventured down from my room. One must expect a certain degree of crudity in a busy seaport, yet Menethil is worse than most. Perhaps it is the fear that infects the place, visible on the anxious faces of the residents. After all, the Scourge (and the Forsaken) are not really that far from the city. I would soon discover that they had more immediate worries at hand.

I took a simple breakfast of salted fish and went out into the town, already filling up with people going about their daily business. I went again to the docks where I spotted a young woman in a simple blue dress, looking out to the sea. I recognized her as the waitress who had been hurt the previous night.

She looked at me, her expression startled. “Oh! It was nothing, though I thank you for your concern. What’s your name?”

“I’m Talus.”

“My name is Livia. Are you from Lordaeron?”

“Yes.”

“I guessed as much, you have that look about you. I’m from Andorhal myself. My husband and I fled here once we heard about the fall of the capital.”

“Many refugees seem to have gone here. Many of them have become beggars.”

She shook her head sadly.

“Most of the refugees who got here early on were able to find jobs. There’s no shortage of them in this place. The ones who came later though... most of them were out of their heads. Andorhal was bad enough when I left, yet I can’t imagine what terrible things those poor souls have seen. How is Lordaeron now?”

“It’s an embattled realm. Southshore still stands.”

“Is it still full of people trying to escape?”

“Yes.”

“Just the same as when Farson and I were there. Farson is my husband.”

“He lives here with you?”

“No. He fights with the remnants of the human armies in the north, against the dead.” Livia’s lips curled at the mention of the undead. “Every morning I come out here, wondering if his ship will be on the horizon.”

“Do you keep in touch with other refugees? The sane ones?”

“You ask many questions. But yes, I do. I scarcely have any time, and neither do they. Every now and then we can meet.”

I sensed that Livia wished to be alone, so I thanked her for her time and left. I spent the rest of the day going around the city. I found a caravan intending to set off for the mountain town of Thelsamar in a few days, and they happily accepted my services as an extra guard. We agreed that I would accompany them to Algaz Station, after which I would go off on my own.

I spent another uncomfortable night in the Deepwater Inn. The next day was a celebration I had completely forgotten about: the Bounty Festival. This holiday is celebrated throughout coastal towns in the human world, it’s roots set in the ancient rites of Dakon, the God of the Sea. Dakon, like all the Arathi gods, is mostly forgotten. The worship of these lost gods subtly persists in certain holidays. The Light never persecuted the Arathi faith. The Arathi pantheon simply died out, as the brutal and capricious deities within offered little for the human race.

Vendors enjoyed a field day as excited revelers filled the streets. Entire families came out in their best clothes, giving a dash of color to the grim port city. An elderly priestess of the Light walked the streets at noon to preside over a feast of seafood given to the unfortunate refugees. Merriment persisted throughout the afternoon with dancing, singing, drinking, and all the other things living humans do when wanting to celebrate. Mostly I observed, though at one point a rosy dwarven girl grabbed my arm and pulled me into a dance, where I did the best I could. It was very generous of her, though I was never much for dancing even while alive.

Vendors enjoyed a field day as excited revelers filled the streets. Entire families came out in their best clothes, giving a dash of color to the grim port city. An elderly priestess of the Light walked the streets at noon to preside over a feast of seafood given to the unfortunate refugees. Merriment persisted throughout the afternoon with dancing, singing, drinking, and all the other things living humans do when wanting to celebrate. Mostly I observed, though at one point a rosy dwarven girl grabbed my arm and pulled me into a dance, where I did the best I could. It was very generous of her, though I was never much for dancing even while alive. The Bounty Festival reached its apex at sunset. A large boat, garishly painted in green, gold, and turquoise, rowed into the harbor. Top-heavy and awkward, there was no mistaking its ceremonial purpose. Menethil citizens, made to look like fantastic sea creatures, manned the oars that propelled the boat towards the docks. At the prow of the ship stood a giant of a man, his skin painted blue and his beard dyed green. Resplendent in a green, scale-patterned robe and a golden crown with three fluting spires, he raised a conch shell to his lips and let out a thunderous blast.

The crowds on the docks parted and a procession came through, led by a ruddy-faced man who looked to be immensely enjoying himself. Behind him, four burly men carried a canopied wooden litter painted to look gold. A beautiful woman in a glittering yellow gown sat on the litter. Strange gold jewelry, similar to the man on the boat, adorned her hands and head. She smiled, and couldn’t resist a bit of grandstanding, waving to the crowd who cheered her as she went by.

The bearers set the litter down at the docks. Standing up to a regal height, she slowly stepped forward to the painted ship, which had moored at one of the piers.

Once on board, the man dressed as a sea-god took her by his side and again blew his conch shell. The crew pushed the boat off from the pier just as the red sun disappeared behind the horizon. The moment it sank from sight, a thousand colors of flame burst in the sky as dwarven fireworks made a day out of night. The crowd shrieked in delight and the celebrations began anew.

The next day was my final one in Menethil Harbor. The streets were only sparsely peopled, as many chose to sleep in after the festival's exertions. Only the docks remained busy, the insatiable demands of commerce keeping the workers occupied.

I traveled to the large, squarish keep in the center of the town, a fortress that doubles as an administrative post. I managed to get an audience with an official named Hagen Silvereye, one of the many dwarves living in Menethil Harbor.

“How do you like our city? Hope you haven’t had any trouble. Menethil has many a footpad about,” he lamented.

“Port cities are usually a bit rough around the edges.”

“Aye, but Menethil wasn’t always like this, lad. It’s that... see, here’s how it is. First, King Terenas is killed by his own son, rest his soul, and the north falls to the Scourge. Then you have all these poor folk trying to escape. Everyone goes here to get to Stormwind, Theramore, or even Auberdine. A lot of them can’t go, so they stay here. Some of them went mad from what they’ve suffered.”

“Does Ironforge rule the city now?”

“Sort of. Menethil’s more or less independent which is fine by me. Our only obligation to Ironforge is to supply troops when needed, and they haven’t asked for many. Problem is, they haven’t been so good about defending us.”

“Who has been attacking?”

“Orcs of the Dragonmaw Clan. You remember them from the Second War, I’m sure.”

“I do.”

The Dragonmaw Clan became infamous in the annals of the Second War by capturing Alexstrasza, the queen of the red dragons. This coerced the entire Red Dragonflight into fighting for the Horde. Despite their control of dragons, the constant fighting decimated the clan's numbers. They made another bid at power a few years after the Second War ended. Again they failed.

“I am surprised that they would still be a threat. I was under the impression that they were nearly annihilated after the Grim Batol incident,” I said.

“Aye, nearly but not totally. They ran up to the mountains; I heard there's a city full of the bastards over in the Twilight Highlands. At first it wasn’t so bad, but with all our boys over in Kalimdor or Lordaeron the Dragonmaw have been making themselves known. A month ago they wiped out an entire caravan. I’ll bet you anything they’re friends with the gnolls and murlocs out in the wild.”

“How much of a threat are they?”

“The orcs? Hard to say. They can’t hurt the city yet, but if they get siege engines we’ll be in trouble. Some people here think that they can’t build catapults or cannon without goblin help, which is nonsense. Even if they couldn’t build them they’d still be able to buy them somewhere. Light help us if they do get catapults.”

“It seems you have a lot of guards here.”

“We’ll put up a good fight, but a lot of the sentries in Menethil are just militiamen. We trained them pretty well but they aren’t a match for orcish warriors. Mind you, I’m not saying the Dragonmaw would win. They’d probably lose; it’s no easy deal laying siege to a city. Hell, I was at the Battle of Blackrock Mountain, I’d know. Still, there’s a chance the orcs would win.”

“How much of a presence do the orcs have here?”

“Blackrock Mountain is still crawling with the bastards. If you ask me, they should recall all the soldiers from overseas and have them flush out the Blackrock orcs once and for all. Thrall can keep Kalimdor, for all I care.”

“I had a few more questions-”

“Go for it,” he interrupted.

“This isn’t the first time I’ve heard about there being problems in Stormwind. Do you know what’s going on there? Up in what remains of Lordaeron we’re too worried about our own problems to think much about the south.”

“Officially there’s a bandit problem in Stormwind. But...,” he whispered, putting his bearded face towards mine, “I hear it’s more like a full out civil war. Stormwind’s a big place, and they haven’t gotten all their population back from the wars, so they certainly aren’t turning away the refugees from lack of space.”

“Has anyone from Stormwind come up?”

“Aye, quite a few in fact. Some of them, the ones from the city, say everything’s dandy. Others say the place is on the verge of collapse.”

“What about Kalimdor? You said that some of the refugees tried to get to Theramore or Auberdine.”

“Not so many want to go to Auberdine. Living on Kalimdor’s scary enough as is and most people don’t feel ready to live in a night elf city. Theramore wants people to come over there, the refugees are just too timid is all. Also there’s all those rumors about Jaina being a Horde sympathizer; I don’t put much stock in them myself, and I think she did the right thing in regards to her father.”

Hagen then said that he needed to get back to work. I thanked him for his time and took my leave.

*********

I left early the next day, accompanying a caravan taking silk to Loch Modan. They had little need for me, as the caravan was already well guarded. Yet a rumor of war hovered in the air, coming not only from the Dragonmaw orcs but also from the Dark Iron dwarves who continued their endless campaign against Ironforge.

The leader of the caravan was a grandfatherly dwarf named Ingni, who looked as if he would much rather be sitting next to a roaring fireplace with a mug of good ale. He was an experienced silk merchant but said that the Dragonmaw wiped out his previous caravan, and that he’d survived purely by luck.

“I thought we were done with the greenskin bastards back in the Second War,” he said. “I fought them back then, even though I was already getting on in years.”

Easily the most interesting traveler in our group was Elsidus, a night elf druid from distant Astranaar. The druids previously existed only among the night elves (though the tauren have recently revived the practice among their own people) and were still something of an enigma to the Eastern Kingdoms. Though Elsidus was aloof, I managed to gain enough of his trust to engage him in some conversation. By relating my own appreciation for nature (which was and still is genuine, even if I am a city-dweller at heart) he began to open up.

“The druids are priests of nature, correct?” I asked.

Elsidus shook his head.

“We are not priests, Talus. We do not worship nature,” he explained.

“The druids are the protectors of nature. Our goal is to seek the preservation of this world.”

“From my understanding that would be somewhat similar to a Horde shaman.”

“Not even remotely. A shaman asks the spirits of the world for help. A druid ensures that a world still exists for those same spirits. Ancient Cenarius empowered the druid orders in ages past. I remember a time when the druids nearly ruled night elf society. I’m sure you know that we eventually forsook this world for the Emerald Dream, at least until recent years.”

Night elves had been immortal until the Battle of Mt. Hyjal. Though they are still long-lived, they too will know the sting of natural death.

“What is the Emerald Dream?”

“Something more beautiful than I could describe. It is nature unsullied by the touch of sentients.”

“How have you adapted to the new mortality?”

“It is difficult, to say the least. I have learned to accept it, unlike many of my brethren who commit abominations in order to regain it. Perhaps it is for the best. As children of nature, we must all remember that nature is eternal. Having immortality may distance us from appreciating that. After all, look at the arrogance it spawned in our leaders, who defied nature’s will in their failed quest for immortality.”

He spoke, of course, of Teldrassil, the great world tree grown as a replacement for the one that fell at Mt. Hyjal. The old world tree was the source of night elven immortality. I knew little of Teldrassil, besides the fact that the night elves are still mortal with the new version.

“So what is your goal here in the east?” I asked.

“Nature in these lands cry out. In the north, the dead taint the earth with their very presence. Here, the dwarves delve deep and build without concern. Make no mistake, Talus. These Wetlands are in danger. It may be generations before it becomes apparent, but they are.”

“Then you’re here to protect the Wetlands in some way? In all honesty, there isn’t very much here besides nature.”

“Oh? What of this road?”

“It’s only a road. The Wetlands are huge!” I protested.

Elsidus sneered.

“Such things begin small. Eventually this entire land may become like Ironforge. I actually seek a guardian of nature native to this land. The ignorant fools in Menethil fear it, though it is of no danger to them. Quite the opposite, in fact. Some call it the Greenwarden or the Bog Beast.”

“You hope it can tell you about the real state of the Wetlands?”

“I already know the real state. I merely seek confirmation. I am of the Order of the Talon, the eyes and ears of the Cenarion Circle.”

The Druids of the Talon are known to be able to transform themselves into stormcrows. I was sorely tempted to ask Elsidus to do it, but I got the feeling that such a request would only irritate him.

“One of the humans gave me this picture which he took with some goblin device. It is yours, if you want it.”

“Thank you. I’m guessing you won’t be with the caravan much longer then?”

“I have already informed Ingni and he has no objections to my departure. I won’t need to leave until we are past orcish territory anyway.”

“One more question, if I may ask?”

“You may ask.”

“Wouldn’t it be easier to simply fly there?”

“It would. However traveling through the air can sometimes distance one from the earth. I may fly back, but I shall walk to the Greenwarden.”

“Fair enough.”

It is something of a chore to go through the Wetlands even with the craftsmanship of the dwarven roads. Dense fog rises from the marsh in the mornings and evenings. Our eyes always strained to see if any orcs hid behind the mist. Rain began pummeling the land after six days of clear weather, and did not stop for another week. Dark talk and moods dominated in the caravan, worsened by the damp chill that permeated their clothes. I wasn’t really bothered by the weather, and Elsidus seemed to positively enjoy it.

We finally reached a fork in the road. The northern path leads to the dwarven town of Dun Modr and eventually to Stromgarde. The other road goes up into the mountains and Loch Modan. Elsidus left us there with barely a goodbye, striding into the embrace of the marshes while rain poured all around him. No one was really sorry to see him go. Despite the rain, the general mood improved since we had passed orcish territory without incident.

We came across a small army of dwarves a few days after Elsidus’ departure, marching at a fast pace in the other direction. Their faces were uniformly grim and they took care to keep their rifles as dry as the weather permitted.

“Has something happened?” asked Ingni.

“You bet it has! The Dark Irons have seized Dun Modr!” yelled a fierce looking sergeant.

“When?”

“A few weeks ago. We just came up from Dun Algaz. It’s a bloodbath in the north.”

“Good luck,” said Ingni, as the army marched by.

The rain slackened into a thin drizzle that night. Frogs and crickets sang from behind the screen of reeds. After setting up an already waterlogged tent, Ingni sat down inside, looking very tired. I noticed that his pale yellow beard was actually white in some areas.

“Oh, this is terrible. Dark Irons in Dun Modr,” he moaned.

“I’m surprised the Dark Irons would come so far up north.”

“It wouldn’t be the first time. Grim Batol isn’t that far from here you know. The Dark Irons took that place, back in the War of the Three Hammers.”

“Are the Bronzebeards and Dark Irons officially at war?”

He looked at me askance.

“Well, they’re killing each other. It doesn’t get much more official than that.”

“Right, but I mean in the government.”

“I don’t know. We had a few scuffles with the Dark Irons before the orcs came. These things come and go. They’d never been able to take Dun Modr though. Truth be told, we thought the orcs had wiped out the Dark Irons. I hate the orcs, but I was ready to dedicate a few alehouse toasts to them for destroying the Dark Irons. Then it turns out the Dark Irons are still around.”

He yawned, and looked up at the dark sky.

“I’m an old dwarf. I’ve seen a bit more than two centuries go by. I thought after the Second War I could finally enjoy what I’d earned. Then my daughter died in a smithy accident, and my son disappeared. I should have stayed in Ironforge, my clan would have kept me funded, but I wanted nothing further to do with that place. Now it seems like even my race’s homeland will be taken from me.”

“I’m sure the Dark Irons will be driven out of Dun Modr.”

“I hope you’re right. Some of my countrymen think it’s a new age, that the Titans will return and set things right. I’ve never seen a Titan though. I’m not quite sure what the fuss is about, the Light was always enough for me.”

The dwarves had begun to venerate the Titans, a fabled race of metallic giants who supposedly ordered the world and created the dwarves. Since the Light advertises no specific deity, interest in the Titans did not preclude the traditional faith. Still, a number of older dwarves distrust the Titans.

Tensions again ran high as we turned south. Some feared running into Dark Iron reinforcements, though that was actually rather unlikely. Others dreaded going by the ruins of Grim Batol. The abandoned Wildhammer stronghold was actually rather distant, yet the fear stayed strong. Many treasure hunters came to the ruins to make their fortune after the Wildhammers left. Few returned and those that did rarely found anything worthwhile. The place fell into ill-repute. The southeastern Wetlands once supported a thriving fishing community, but the anglers abandoned the place, wanting nothing to do with Grim Batol's gloomy remains. Its presence tainted the entire region.

This was not the end of the story. In the Second War, the Horde found Grim Batol to be a perfect base of operations. As it was a city buried into the mountain, it proved nearly impervious to conventional attack. It was there that Zuluhed, the Dragonmaw shaman, ensorcelled the Red Dragon Queen. Surprisingly, the Dragonmaw left the fortress as Alliance forces drew near, choosing to disperse into the marshes.

They returned to Grim Batol after the war, seeking to reunite the Horde. They still controlled Alexstrasza, and by extension the rest of the Red Dragonflight. Their hopes came to naught. Alliance operatives freed Alexstrasza and she turned against her captors with a rage that is now legendary.

As I noted earlier, I had thought the Dragonmaw Clan completely wiped out.

For whatever reason the Red Dragons never left Grim Batol. Alexstrasza herself allegedly remains in the dead city. Only the insane or feeble-minded approach the place. Dragons have never been the friendliest of beings, and the Red Dragonflight is famed for its paranoia.

Everyone breathed a sigh of relief when we reached the tunnel complex of Dun Algaz. Dun Algaz is a marvel of engineering. Great hallways are carved into the living rock of the Khaz Mountains, rising diagonally from the mire of the Wetlands into the high plateau of Loch Modan. It should have been impossible to build. A particular marvel is that Dun Algaz was not built for defense, or to satiate the ego of a king. Instead it was made for the pragmatic purpose of trade. With its completion merchants could reach the lucrative markets of Dun Modr and Lordaeron without navigating the treacherous mountain paths, which used to claim scores of lives every year.

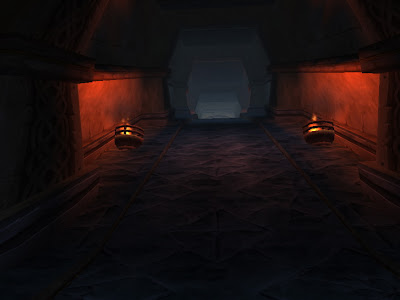

This did not mean that it is an easy journey. The tunnels rise steeply and I understood why the dwarves rely on sure-footed mountain rams to pull their caravans. It takes around a day to traverse each tunnel. Subterranean existence is second nature to most Bronzebeards however, and few seemed bothered by it. Fiery braziers, eternally lit with the power of gnomish artifice, give a ruddy glow to the long tunnels.

We stopped for a night in one of the open spaces between tunnels. The damp, heavy air of the Wetlands was gone, replaced by the rarefied mountain atmosphere. From our vantage point we could see the broad river valley of the Wetlands spread before us, colored red with the setting sun.

A patrol of soldiers came by and talked a bit with Ingni, mostly at the latter’s insistence.

“I’m sorry tradesman, we don’t know what’s happening in Dun Modr yet. Light knows I’d like to be there to throttle those damned Dark Irons though,” commented one soldier with a bushy black beard.

“How were they able to get through here?” demanded Ingni.

“Are you daft?” interjected the other. “They never came through here, and we’d not have let them if they tried. The Dark Irons went the hard way, clambering each and every mountain until they got to Dun Modr. The bastards are persistent, I’ll give them that much.”

“Don’t yell at the man Adgus,” scolded the first soldier. “It’s only natural for him to be worried, I’m worried myself.”

“Are the Bronzebeards holding their territory though? Dark Irons in Dun Modr, orcs all through these mountains... it seems like the Second War all over again,” said Ingni.

“Ah, well I hate to tell you this, but we wanted to warn you that we’ve heard that there are some orcs about. Not many of them mind you, nothing your guards couldn’t handle.”

“What? What if they tell the other orcs about us—”

“Relax, relax. By the time they got back to the other orcs you’ll already be in the Loch. I’m sure some of our lads have already shot them down.”

“I pray you’re right.”

We continued climbing up. The air became thinner, something that would have made me light-headed if had still been alive. Despite the warnings we still did not encounter any Dragonmaw, though one of the guards swore he saw an orc in the distance. With no other option, we simply trudged upwards.

No comments:

Post a Comment