Only a naturalist can truly do justice to the steam-laden wilds of Un’goro Crater. Traversing the rocky path down to the crater is akin to entering a different world. The scorching desert sun vanished behind the deep green of the forest's canopy and its masses of water vapor.

Ja’gahn laughed as we stepped into the warm mist, sounding immensely pleased.

“I never much cared for the desert,” he said. “The jungles are much more to my liking.”

Un’goro Crater is nearly an axiomatic jungle. Around the great trees whose limbs block out the sky are tangled thickets of smaller trees. Drooping cypresses and mangroves grow from the murky waters of the Marshlands, the sodden region in the southeast crater. Dense ferns cover the muddy ground, and the constant chatter of birds and amphibians drowns all other sounds.

The Marshlands are a treacherous area. We spent three-and-a-half days going through the swamp, a good portion of that time spent waist-deep in water. Before going in, Ja’gahn covered himself with an oily substance that would repel leeches. I had bought some at his insistence, but (as I had suspected) a short experiment proved that the leeches had no interest in my dead flesh.

Raptors of alarming size stalk through the reeds of the Marshlands. They hunt at night, and we were kept awake by their fierce bellows echoing in the jungle dark.

“Raptors are clever beasts. They are speaking to each other,” Ja’gahn said.

“Pack predators sometimes do have forms of vocal communication,” I agreed.

I doubt I would have been able to navigate through Un’goro Crater without Ja’gahn’s help. Years of experience had given him the uncanny ability to spot quicksand and avoid the raptor hunting grounds. His mood improved visibly as we put Tanaris behind us. Ja’gahn told me stories of his years as a fisherman on the Isle of Kezan, and of his time as an explorer in the Steamwheedle Cartel’s service. That was how he had first come to Un’goro.

“Are you still employed as an explorer?”

“My contract expired. I might renew it someday, but for now I want to do things on my own. Life isn’t much fun when you always have to report your doings to some goblin manager.”

I told Ja’gahn of my own travels. He took special interest in my stories about the Hinterlands.

A defining aspect of Un’goro Crater are the tremendous lizards that crash through the jungles. While raptors can be found all over Azeroth (and, according to some records, even in Draenor) Un’goro also plays host to beasts like the diemetradon, stegadon, pterrordactyl, and devilsaur. Ja’gahn was emphatic about the danger posed by the devilsaur, a great bi-pedal carnivore that has the uncanny ability to sneak up on travelers despite its tremendous size.

Diematradons are a common sight outside of the Marshlands. The beast's general build is similar to the basilisk’s or crocolisk’s, though the most notable feature is the single great fin that rises from each diemetradon’s back. They are carnivorous but Ja’gahn said that they would leave us alone provided we not get too close to them.

Stranger still are the lashers, ambulatory flowers that reach up to six feet in height. They slither through the jungle on fleshy roots, seemingly oblivious to their surroundings. As far as I could tell, they gain sustenance the same way as any other plant.

Un’goro has barely been touched by the hands of any intelligent race. Kaldorei histories for the War of the Shifting Sands mention that the Qiraji were unwilling or unable to field their insect armies in the area. The elves never found out why this was so, though they had many theories.

“Did you know the dwarves even sent an expedition here, three years ago? They stayed in the Marshlands, collecting bones and dirt. A goblin told me they were looking for cities of metal giants," said Ja'gahn, one morning.

“Ah yes, the Titans.”

“That’s what he called them. Have you ever seen a Titan?”

“No. I don’t think anyone has.”

“The goblin said that the dwarves thought Un’goro Crater was where the Titans tested life. That’s why there are so many strange creatures here; leftovers from the giants’ magic.”

Torrential rains lash the forest canopy of Un’goro on a daily basis. No one is entirely sure how Un’goro is able to get so much rain, since it is surrounded by deserts. Dwarven scholars have theorized that the Titans had somehow sealed off Un'goro from the surrounding climate.

Neither of us were prepared when the forest floor suddenly gave way, causing us to tumble head over heels into the earth. I only caught flurried glimpses of strangely lit caverns before crashing into a warm and spongy surface. Ichor coated my skin, but astonishment soon surpassed my disgust.

Walls of hardened resin flushed in dark and mottled colors surrounded us, coiling in tumorous masses. Globules of slime clustered on the ceiling, dripping ooze onto the ground. I heard Ja’gahn gagging in revulsion behind me, probably sickened by the alien stench inundating the caves.

The two of us had landed in some kind of fleshy tunnel that stretched a great distance in both directions. An immense insect clung to a nearby wall. In appearance it resembled a grotesquely enlarged firefly, its bloated body alight with orange phosphorescence. Streams of viscous yellow liquid dripped from its belly.

Ja’gahn and I had stumbled into a silithid hive.

“Destron! Do you have any magic that can lift us out of here?” demanded Ja’gahn.

“I do not.”

“Damn, this is not good. I’ll get the rope; keep an eye out for bugs.”

“Understood.”

I heard them before I saw them, a sharp clicking echoing down the oozing caverns. A quintet of silithids, looking like freakish crosses between beetles and spiders, scurried into the chamber where we had fallen. I readied spells, though the insects made no hostile motions. They hurried around the room in a state of confusion.

“Destron, kill them!”

“They aren’t attacking us—”

“They will! Go, you fool!”

Ja’gahn grabbed a rope and grappling hook out from his backpack while I fired off an arcane explosion amidst three of the silithids, killing one and immobilizing another. The third had lost two legs in the burst, and tottered in to attack on the remainder. It was far enough away for me to slow it with a frost bolt, and finish it off with arcane missiles.

Ja’gahn flung the rope upwards. The grapple landed on solid ground but failed to hitch on to it, falling back into the pit with a thud. Ja’gahn cursed and I heard a note of panic in his voice. The two remaining silithids fled the scene, but the clicking sound grew louder, accompanied by hoarse and rattling bellows.

The bladed legs of the silithid warriors enable them to run at fantastic speeds. I barely had time to react to the first warrior that charged into view. Claws, razor mandibles, and a vivid yellow carapace created the impression of a dreadful war machine.

The warrior lashed out at my head, missing it by inches. Rolling to the side, I saw a field of moving yellow bodies farther down the tunnel. Getting to my feet I saw Ja’gahn gripping his spear, jammed deep into a crevice of the warrior’s shell. The insect hissed and shrieked, spraying pale green blood from the wound.

Ja’gahn jumped off and grabbed the rope, which he must have thrown up a second time when I dodged the silithid. Clambering up, he yelled at me to follow. The legs of the wounded silithid slashed reflexively and I barely jumped over the jerking blades. Enraged silithids filled the tunnel, claws clicking in frustration as we escaped the nest.

We ran as soon as we climbed to the top, and continued to do so until we’d reached a considerable distance from the hive. Ja’gahn fell to the ground, breathing heavily.

“How did you know where to strike the warrior?” I asked.

“I didn’t know. Dumb luck, that’s all it was.”

After a brief rest, we moved on at a slower pace. We saw no signs of pursuit, but we remained on guard just the same. Ja’gahn apologized for blundering into the trap.

“Did you know the hive was there?” I questioned.

“No.”

“Then you need not apologize. You did a remarkable job getting us out of there.”

“Like I said, that was luck, not skill. You thank the Elawi spirits or the Loa for getting us out of there. I did not guide that spear. I will not accept the rest of the payment for this job. I don’t deserve it.”

“It is not an issue. I have little need for money—”

“No, this discussion is finished. I am not like other trolls, for there is no tribe that will call me honorable. Zandalari and Sandfury alike consider me a stranger. I must make my own honor in this strange world of ours.”

I tried a while longer to convince him to take the rest of the payment, but he steadfastly refused. Ja’gahn was quite serious about his role as a guide.

*********

I suspected that Ja’gahn had been exaggerating when he warned me of the devilsaur’s uncanny stealth.

He was only being accurate.

The jungle thins out a little bit in southwestern Un’goro. Great boulders are strewn across the soggy landscape, and the tall grasses conceal bogs and pools of mosquito-infested water. The dinosaurs are completely dominant in this part of the region, and terrible roars sound across the humid plains day and night. Ja’gahn said that they came from great lizards called stegadons. I never saw any, though they allegedly look like reptilian kodo beasts. Raptors are mostly (and mercifully) absent, yet diemetradons are ubiquitous. We twice ducked under the ferns for cover when screaming pterrordactyls soared overhead. The winged reptilians (supposedly) do not hunt humanoids for food, but they are extremely territorial and aggressive.

Ja’gahn’s almost supernatural calm served as a testament to his abilities. Even I began to feel anxious and frazzled in that lizard-haunted wilderness. There is no avoiding the ominous signs of massive predators: flooded claw-prints in the muddy ground, and gargantuan bite marks on the trees.

“I do not wish to hurt you, but you should know that I have a rifle trained on the Forsaken’s head,” announced a reedy voice, speaking in heavily accented Orcish. Ja’gahn grabbed a spear, his sharp eyes seeking the source of the voice.

“As I said, I do not want to kill anybody. But you have to tell me what you are doing here.”

I motioned for Ja’gahn to stand down.

“We are traveling to Silithus,” I announced.

“Ah, a lot of people are going that way. For the war effort?”

“I go to learn about Silithus, though I will probably aid the Horde forces stationed there. What about you?”

“My name is Zilbir Sparklarm. I’m a researcher and adventurer with the Marshal Expedition, which I am badly hoping is not destroyed.”

Judging from the voice and name, I deduced that we were dealing with a gnome. The voice came from a clump of reeds about fifteen feet away.

“I’ve not heard of the Marshal Expedition.”

“A research team that went to Un’goro. We had some, ah, trouble with the native fauna. It’s a combined Horde and Alliance effort; that’s why I’m making some attempt to be diplomatic here.”

“A prudent decision. We do not mean you any harm. From you words, I judge that you do not wish to hurt us either.”

“I would prefer that did not become necessary. I am going to reveal myself; however, my weapon will be trained on you. Please make no sudden movements.”

A bedraggled gnome rose up from the reeds. His clothes hung in tatters, but his rifle was in remarkable condition. Zilbir’s face suddenly came alive with terror.

“Get down on the ground and stay very still!” he yelled, before disappearing back in to the foliage.

Not knowing what else to do, Ja’gahn and I followed his lead. I felt faint tremors as I pressed my body into the earth.

A clawed and colossal foot stamped into the ground in front of me. The foot (easily six feet long) came at the end of a white-scaled leg, itself a pillar of muscle and sinew. The devilsaur stood so tall that I could not even see the top of its head. My vision ended at the impossible jaws that looked able to crush stone.

The devilsaur paused, making a kind of snuffling noise. It roared, an unbelievable sound that shook the very earth. A few more minutes (though they felt more like hours) passed in dreadful silence. The devilsaur let out another cry before lumbering off to the west. I did not get to my feet until I was quite certain that the beast had passed.

“Are you still alive? Or undead, as the case may be?” inquired Zilbir.

“Yes, we are. Thank you for the warning. I don’t know how it managed to sneak up on us like that.”

“The stealth of the devilsaur is both uncanny and biologically improbable. I doubt that the explanation is supernatural, though I cannot rule it out,” commented Zilbir, who was remarkably nonplussed.

Ja’gahn was reluctant to have Zilbir as a traveling companion, but I convinced him that we had nothing to lose. Perhaps his perceived failure with the silithids made him reluctant to take a stand against me. Zilbir deemed us trustworthy, and offered to take us to the Marshal Expedition, assuming he could find it.

“There’s a ridge in the mountains to the north that we decided would act as a safe spot, if the animals became too much of a problem. I have a lot of tracking experience, so I will probably be able to find it,” he explained.

Zilbir was an interesting man, somehow managing to be both a sheltered academic and tough adventurer in equal degrees. His mannerisms were almost stereotypical for a gnomish researcher, yet the fact that he had survived on his own proved his strength. Zilbir knew the dangers about as well as Ja’gahn.

“Why did the Marshal Expedition set up camp in the Terror Run?” I asked one night, as we sat around a flickering camp fire. Terror Run was the name Zilbir had given to the dinosaur-infested southeast.

“Because it’s a wealth of biological information, of course. The varieties of flora are distributed fairly evenly around Un’goro. This is not the case with the fauna. Furthermore, our position enabled us to examine the silithids.”

“Ja’gahn and I had an encounter with them.”

“They are exceedingly dangerous. One of the major sponsors of the expedition was the Cenarion Circle. We could only receive the funding if we investigated the silithid problem. I was at the silithid hive, the Slithering Scar, when the camp was destroyed.”

“Why didn’t you have defenses against the beasts? Seems foolish, I think,” grumbled Ja’gahn.

“A lack of defenses would have been quite foolish, but we had an arcane field that repelled the dinosaurs. It was gone when I came back; whether something broke it, or it simply failed, I do not yet know. The field was never as reliable as we hoped, so I suspect the latter.”

Ja’gahn grunted.

“What did you learn about the silithids?”

“I made two expeditions to the Slithering Scar; one successful, with Hol’yanee Marshal, and another that was less successful. I went with a Cenarion warrior who did not escape alive. I was able to learn about silithid life in both cases.”

“What do the silithids eat?” I asked. The question had been bothering me for some time.

“Did you see the big glow-bugs that were clinging to the walls of the hive?”

“I did.”

“You might have noticed that they were oozing a sort of yellowish sap. It’s a mix of sugar and various essential proteins that I’ve called ‘silicose.’ Silithids eat that. The luminescence of the bug is a by-product of the silicose creation process.”

“They’re almost like cows then?”

“In a matter of speaking.”

“And what to the glow-bugs eat?”

“I do not know yet. It must be something that’s very common and easy to obtain, however.”

“How many different kinds of silithid exist?”

“At least five: workers, flyers, tunnelers, reavers, and larva. I think larva can turn into any of the other forms, depending on the needs of the hive. This is just a theory though, I have not yet been able to prove it,” he cautioned.

“I saw one form that looked like a cross between a beetle and a spider. They made no move to attack, and came when we fell through the ceiling of the hive.”

“Those would have been workers. Workers can fight, but not very well. Reavers and flyers are the warrior castes.”

“And tunnelers?”

“They act as a midway point between workers and warriors. They use their claws and a corrosive spray to create the tunnels. After they make a tunnel, workers will coat it with a fleshy substance that they excrete after eating silicose. This strengthens the tunnel.”

Ja’gahn made a disgusted sound.

“The tunnelers are capable of fighting?”

“Quite. Some tunnelers also carry larva with them; I do not know why.”

“Is there anything like a silithid queen?”

“We did not find one, but I suspect there is one.”

“Would you say the silithids present a threat?”

“A major one; potentially worse than the Scourge. Potentially. There is also some evidence of extra-normal powers spurring the silithids to war.”

“That would be the Qiraji,” noted Ja’gahn.

“Yes! The Qiraji, several of my colleagues have been trying to get information on them. The records are pretty scant. The night elves fought them back in the War of the Shifting Sands, but they did not seem to actually bother learning about them,” complained Zilbir. “Battle tactics and a few remarks on their cyclopean cities; that’s about it. What could you tell me about them?” asked Zilbir.

“I know little; I’m not a keeper of lore. I know they were monsters that were old before the elves were born.”

“I see. I don’t suppose there’s a specific record of their first appearance? We have read some of the codices, but even the Zandalari histories are fragmented about these Qiraji.”

“The Qiraji worship the Old Masters. Dark things come from them.”

“Such as?”

“Not for me to know,” muttered Ja’gahn, clearly uncomfortable.

“Could you refer me to someone who does know? It would be helpful if I manage to escape the Crater.”

“Perhaps on Zandalar, but they do not take kindly to non-trolls.”

“Hmm, well I might be able to contact a few trolls through my associates in the Cenarion Circle. Thank you for your time.”

The next day brought us to the outskirts of Fire Plume Ridge, a mass of great igneous blocks thrown carelessly together in the midst of the jungle. As implied by the name, the mountain is volcanic. It simmers in a state of constant readiness. Rivulets of lava ooze out between citadels of dark rock, while plumes of smoke bleed up from the ground.

“I’m not a geologist, so I do not know too much about Fire Plume Ridge. But it’s been in a constant state of low-level activity since we arrived. We almost considered abandoning the crater because of it,” explained Zilbir.

“You were worried that it might be a prelude to a massive eruption?”

“That was the concern, yes. The other thing is that the level of smoke that constantly leaks out into the air should have had a very deleterious effect on the region. I mean, the skies should be black by now. Somehow, everything beyond the reach of the volcano is fine.”

“Do you have any idea why?”

“Given how little is actually known about volcanoes, there’s probably just something we’re missing. On the other hand, it is entirely feasible that there is a supernatural explanation. I’m not going to hazard any theories right now. Ringo, our geologist, said the place was infested with fire elementals, so that might have something to do with it.”

We passed Fire Plume Ridge in a few days, returning again to the trackless jungle. The dense undergrowth proved a severe impediment to our progress. Ja’gahn took the lead, cutting a path with his machete. This task restored some of his confidence. After a day in the thicket, the trees cleared and we stepped into a vast plain. Ferns and tall grasses covered the ground and the entire place reminded me unpleasantly of Terror Run. I commented on this to Zilbir.

“We’re near the Lakkari Tar Pits. The dinosaurs are not so common in this place. If they get stuck in tar, they’ll get sucked down. This applies to us too, by the way, so be careful.”

We soon came across the first of many tar pools. Some of the tar pits are quite large, ranging up to a hundred feet across. Slick, oily bubbles slowly form on the surface before popping. A sulfurous stench pervades the hot, tropical air of Lakkari. Zilbir and Ja’gahn both gagged at the smell, and I found it unpleasantly distracting. Bleached dinosaur bones rest mired in the tar, serving as a grim reminder of Un’goro’s ubiquitous danger. Not even the great devilsaurs are completely safe in that place.

Un’goro is as full of surprises in Lakkari as it is anywhere else. The tar pits have spawned shambling creatures made from muck and oil. Zilbir warned us to keep our distance.

“It’s only a matter of time before a mage casts a fireball at one of these tar pits and causes a disaster,” muttered Zilbir. “Then again, maybe it’ll be like Fire Plume Ridge and not have any effect.

Four days of travel through the sweltering tar pits brought us to the northern edge of the Crater. We walked east for a little while before Zilbir stopped at a great boulder.

“Here it is!” he exclaimed.

Pointing ahead, we saw a crude path running up into the mountains. We had arrived at Marshal’s Refuge.

*********

“We’re lucky to be alive.”

Night had fallen, and the ragged survivors of the Marshal Expedition gathered around a large campfire. The 21 surviving researchers maintained reasonably good spirits despite their many setbacks. Food sources in Un’goro are plentiful enough for those who know where to look, as is water. They greeted Zilbir’s return with enthusiasm. Ja’gahn and I were accepted more reluctantly, until I assured the researchers I would provide food for the two of us.

Expedition leader Williden Marshal explained the events that had forced them to flee the Terror Run camp. Zilbir had already told me that an arcane field protected the camp from the dangerous beasts. Unfortunately this field was difficult to maintain and consumed a great deal of mana. Finally, it just died one morning. The resultant dinosaur attack killed eleven researchers, and three more perished on the way to the Refuge. There was also the Cenarion warrior who had been killed by silithids during Zilbir’s exploration. Four people were still missing.

“Frankly, we would have had to abandon the camp anyway. We all knew that the field was going to die on us eventually,” sighed Williden.

Everyone in the Marshal Expedition came with extensive knowledge of how to survive in the tropics, which perhaps accounted for their strong morale. The Expedition mostly consisted of humans, dwarves, goblins, and gnomes. Three orcs and two tauren stood in for the Horde.

“The shamans had heard strange things of this land. They wished to learn, so they sent us,” said Kocham Runetotem, one of the tauren.

“Who among you are shamans?”

“Myself, and Varm Redmoon,” he replied, pointing to a fierce orc who was sitting near the campfire.

“How have you gotten along with the Alliance?”

“Well enough. I had concerns, but I am happy to say that they are groundless.”

“I know that the expedition is being sponsored by the Cenarion Circle and the shamans. Who else?”

“The Earthen Ring is another supporter.” The Earthen Ring is a loose affiliation of orc, troll, and tauren shamans. It wields a great deal of influence in Horde policy, but very little in the way of direct control. “To answer your question, the Royal Archaeologist’s Society and the Explorer’s League of the dwarves are sponsors, as is the Gnomeregan University-in-Exile, and the Stormwind Exploration Corps.”

“I’m surprised the Apothecarium did not send anyone,” I remarked.

“I believe that there may have been some disagreement or misunderstanding between the Apothecarium and the other organizations involved,” described Kocham. He spoke in a very diplomatic manner.

“I despise the Apothecarium, and I commend your sponsors for not inviting those poisoners.”

“I see. Yes, the dwarves and humans both protested the inclusion of the Apothecarium.”

Politics are an understandably dicey subject in Marshal’s Refuge. Williden had explicitly forbade political discussion in the Refuge. I only spoke a little to Williden, but I was impressed with his leadership ability. Some of his success could probably be credited to the outside threat of the dinosaurs. Aside from occasional pterrordactyl flights, dinosaurs usually avoid the mountains, but the researchers cannot afford to let up their guard.

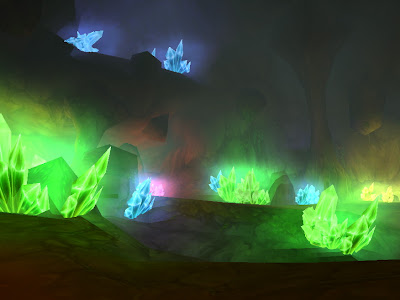

The importance of Marshal’s Refuge lies in more than the accessible sources of food and water. There is also an unusual cave that winds some way into the mountains. Within its earthen confines are clusters of softly glowing crystals that grow from the rock, colored in yellow, green, blue, and red. The light is soft, but still strong enough to make torches unnecessary.

Because the Refuge had been so recently established, the researchers never found the time to really investigate the crystals. This was not the their first encounter with the curious stones; several reported seeing identical crystals set in the jungle's loamy soil. The Crystal Cave (as it had been imaginatively named) is refreshingly cool compared to the sticky and torrid air of Un'goro. The researchers nonetheless set up their camps outside, so as not to disturb the crystals more than necessary.

An intense gnomish woman named Jindra ‘Collie’ Coilyoilspringer was the only researcher to have devoted much time to studying the crystals. When not helping to set up the Refuge, she spent her time in the innermost chamber of the cavern, which the Researchers call the Chapel. She permitted me to walk through the Crystal Cave, though she warned me not to touch the crystals.

Jindra sat down on the stone floor, looking simultaneously tired and fascinated. After some small talk, she began to describe the crystals.

“They are actually all over this crater. Somehow, a lot of people have a hard time noticing them. Except for dwarves and gnomes.”

“Any idea as to what they notice it?”

“Probably because we’re shorter. I’d like to test some crystals, but I’d rather not damage the ones in this place. Later on, once we’re settled in, I might try to get some from the jungle.”

“You are not worried about damaging those?”

“I have to find out one way or another, don’t I?” she protested with mild indignation. I nodded.

“Anyway,” she continued, “I think they might have something to do with the Titans. Have you heard the theory about the Titans in Un’goro?”

“That this was where they experimented with life?”

“Correct. There are some very strange aspects to the climate here in Un’goro. As you probably know, it’s usually raining here. If it isn’t raining, it’s getting ready to rain. At the same time, it’s pretty deep inland and surrounded by mountains and desert. Odd, wouldn’t you say?”

“Quite,” I agreed.

“Here’s the—actually, let me show you. Follow me, please.”

I followed Jindra outside, where the muggy air carried the scent of ozone. Dark clouds brewed overhead, and thick drops of rain had already begun to fall.

“Oh, do I ever miss the snow of Dun Morogh. Anyway, take a look up there. Where are the clouds going?”

“They appear to be going south. Curving south, in fact.”

“Indeed they are! If we were standing in the western part of the crater, the clouds would be moving east. In the east, they’d be moving west.”

“So clouds and rain are drawn to this place?”

“It is. Plenty of researchers have already remarked how unusual it is for a coastal desert like Tanaris to be so big. Or how Tanaris and Silithus are on the same latitude as Stranglethorn, but are as dry as bones. Un’goro sucks in all the rain.”

“How?”

“Right now, the working theory is that the Titans did it. We do not really know. Some of the dwarves are very keen on this idea, but I want to find out a little bit more. The dwarves have a hard time staying objective about anything involving Titans.”

“What happens after the rain falls?”

“The clouds dissipate. Presumably there is also a mechanism that lets some of the vapor escape.”

“All storms are drawn down here?”

“You know, it might be selective. Like I said, we don’t know much. All that we do know is that clouds seem to move here.”

A fierce downpour struck that night and lasted into the next day. Morning revealed a sea of mud around Marshal’s Refuge. No lasting damage had been done. Towards the evening, the researchers discussed their next course of action. They decided to send four of their number (including Zilbir) to Gadgetzan. Their goal was to try and get regular supply shipments from the goblin metropolis. The only problem with that idea was the expense.

“Here’s the thing Williden; whether we try to get supplies via overland, or by air, it’s going to cost a lot,” said Spark Nilminer, a goblin.

“I know, I know,” mused Williden.

“We need to figure out something besides money that we can offer the goblins,” suggested Spark.

“Money is all they ever want,” grumbled Varm, the orc shaman.

“Varm...” warned Williden.

“Hey, it’s almost accurate,” interjected Spark. “Anyway, there’s war brewing in Silithus. Most of the troops are coming over the northern mountains via zeppelin, but there might be a few soldiers of fortune or adventurers who come in through Un’goro. The mountains north of Silithus are nearly impassable, and it’s not like most of them can afford zeppelins of their own. We can make this camp a resupply point.”

“No, no. Armies tramping through here could do irreparable damage to the Crater’s ecology,” disagreed Williden.

“There won’t be that many of them. Anyway, I think the ecology is more likely to do damage to the travelers. Hell, we’ve all seen what those devilsaurs are like.”

There were some murmurs of assent.

“I just think if we provide a rest point for travelers through Un’goro—and I’m pretty sure there’s going to be a lot of them in the near future—Gadgetzan will be more inclined to help us. We may have to split some of the profits, but since profit isn’t the goal of this Expedition, I can’t see how it would be a problem.”

The shamans both made fierce protests to the idea, and Williden adjourned the council until the next day. I would not be there to see it. I departed Marshal’s Refuge with Ja’gahn as the sun rose over the unspoiled greenery of Un’goro. Ahead of us waited the insect realm of Silithus.

Good evening Destron!

ReplyDeleteI never had imagined that Un'goro Crater would be a haven for prehistoric forests and jungles as well as dinosaurs! I must admit I had never really paid much attention to it in the past but your entries provide anyone who read them, a sense of excitement and desire for knowledge, at least it does for me.

The part of in which they fell into the silthid hive was definitely an interesting way of talking about the Slithering Scar itself and had that whole Indiana Jones feel to it which was incredible!

It is no doubt that these insects will stir a lot of trouble in the future and are a major threat that must be dealt with sooner than later, hopefully both horde and alliance will soon realize this.

Thank you for another great entry!

Hehehe loved the part about the devilsaurs :)

ReplyDeleteStill re-reading and loving it, though weird question, didn't Ja’gahn used to reference the Titans specifically as the Travellers?

ReplyDeleteHey, good to hear from you?

DeleteHm, it's possible that I changed it. When I originally wrote this section, I don't think the Titan influence on Un'goro was as clear, and I may have updated it as more lore became available.