The tunnel descended steeply over the next several miles. Sneed led the way in silence, his lantern guiding us forward. Long hours passed in the subterranean passage and we made camp so that Sneed and Milg (the surviving guard) could rest.

“Damn, I’ve never had that much trouble there. Everything’s gone, just like that,” mourned Sneed.

Milg made a whimpering sound. He’d been badly shaken by the attack.

“How much longer is the tunnel?” I asked.

“We’re pretty close to the exit. I’m going to have to find a new way to get money. Even if the tunnel were still passable I don’t want to go anywhere near Darkwhisper Gorge again.”

We all felt relief when the tunnel ended at a lonely windswept ledge, lit by the ruddy glow of the setting sun. Below us spread the red forests of Azshara, trapped in an eternal autumn.

It took us the rest of that day and all of the next to get down from the mountains. The path is narrow and treacherous, and I’d have surely gotten lost without Sneed’s guidance. He explained that he had learned survival skills by working as a prospector for the Venture Company.

Azshara is a land of extraordinary beauty and decay. Leaves of red, gold, and orange adorn the trees. Mighty stags walk between the trees, grazing on the yellowing grass growing underfoot. The land is rugged, abounding with rocky hills and forbidding drops. The only sign that sapient beings had ever lived in Azshara are the crumbling elven ruins tucked away in the mountains and forests. Even they seem more a part of the landscape than a deviation from it. Shrubs and saplings grow from broken flagstones, and the remnants of tumbled pillars have eroded to the point of looking like natural rocks.

I had learned a little bit about the region from the Kaldorei. In the time before the Sundering the elves named it Azshara in honor of their queen. After the Sundering, the land kept its name to forever remind the world of the sins she committed.

Histories report that the land of Azshara once looked similar to Ashenvale: a boundless, evergreen forest. Queen Azshara’s refined tastes demanded more. She loved the transformation undergone by the southern forests during autumn, and decreed that her namesake land should be the same way. Using powerful magic, Azshara and a cadre of Highborne arcanists changed the forests, turning green into crimson.

The elves adored their queen and many praised the land’s transformation as a great work of arcane skill. Yet wiser elves felt only horror. The evergreen forests of Azshara were never meant to undergo such a change. The druids implored the Queen to reverse her action, knowing that her magic meant a slow torment for the forest. She refused, mocking them for their short-sightedness. What did nature matter, she said, when the glories of arcane could so easily reshape it? Thus begun the social rift that would one day lead to the catastrophic War of the Ancients. After the Sundering, many druids attempted to undo Azshara’s enchantment, but none even came close. Azshara remains in an unnatural autumn, never dead but always dying.

Azshara is considered a land of ill omen to the elves, though a few hardy souls did settle there in the millennia after the Sundering. The coastal town of Salunthris provided a haven for those attracted by Azshara’s haunting beauty. Sadly, Salunthris is no more. It was only a few years since the Battle of Mt. Hyjal when Illidan stormed his way ashore with an army of naga, destroying much of Salunthris. The survivors abandoned their homes, fleeing westwards to Astranaar. The peace treaty with the Horde still held at that time, and the orcs at Splintertree aided the elves on their flight.

The third day of travel in Azshara brought us to the lonely orcish outpost of Valormok. Valormok is little more than a collection of rude huts, tents, and wagons collected in an autumnal valley. If the orcs were greatly disappointed at Sneed’s lack of cargo, they did not show it.

Valormok’s main purpose is two-fold. The most pressing concern is security. To the south is the Alliance base of Talrendis Point, itself no larger than Valormok. Talrendis Point may conceivably act as a staging area for attacks on the Warsong Lumber Mill, and Valormok exists to ensure that it never becomes such a threat. The second objective of Valormok’s existence is to search the elven ruins for artifacts of immense power.

There has not yet been any conflict between Valormok and Talrendis Point. The two sites are both more interested in survival than in warfare. While Azshara is not a very hostile land, it is quite remote. Shipments from Splintertree Post in Ashenvale cannot be relied upon due to interference from Kaldorei scouts and demonic satyrs. Likewise, the foreboding antiquity of the land puts something of a damper on martial spirit. The orcs of Valormok once even provided shelter to a group of humans and dwarves fleeing from a pack of satyr marauders.

Of note is the fact that Valormok serves as something of a hardship post for the orcs. While many of the warriors there are of the Ebonflint War-pack, which was started by reformed grunts of the Blackrock and Black Tooth Grin clans, others are there as punishment. In some cases, they are sent to do penance for poor choices on the battlefield. In others, it is because they somehow displeased a superior.

“Honor is a tricky thing. Sometimes you do what you think is honorable, but it turns out you really haven’t,” said a young orc warrior named Mrok. Mrok was (and technically still was, albeit on a probationary status) a warrior of the Bloodgaze War-pack. He continued his tale.

“The officer of my band was Scron Sharpspear, a fierce and brave warrior. At first I was honored to serve with him. He is famous for his battles against the centaur, having once managed to kill five in one day! Yet I, in my inexperience, thought him headstrong. There were five of us on patrol in Durotar, not too far from the Razor Hill. We found an encampment of 30 quilboars—they are a vicious race of swine-men, if you haven’t heard of them—and he ordered us to attack. I protested, thinking that it was foolhardy. In the end, Scron and I were the only survivors, though we felled eight quilboars.”

“What happened then?”

“I rankled, thinking he wasted the lives of my comrades. Indeed, Orgnil Soulscar, the warlord of Razor Hill was outraged. He and a number of others questioned Scron, and made me a witness to his deadly bravado. In the end, they stripped him of his rank and forced the Bloodgaze authorities to send Scron to Brackenwall Village in Dustwallow. They thanked me for my testimonial, though in truth I felt conflicted. After all, he was a great warrior.”

“True, but those who died on his headstrong charge might have become even greater warriors later on, if they had lived,” I pointed out.

“I’m not so sure. They did get killed, after all. Anyway, the Packlord of the Bloodgaze found out, and he told me of a warrior’s duty to stand by his brothers at all times. His wrath was terrifying, even to me. As punishment for testifying against Scron, he sent me here.”

“I think you did the right thing,” I said.

“I do not know any longer. I was like a sniveling goblin, going back against a great warrior because I thought his tactics were foolish, even though I myself was young and inexperienced! I betrayed a fellow Bloodgaze member. Orgnil was right in punishing Scron, but I should not have helped her. The War-pack is among the greatest of all bonds.”

“Did Orgnil defend you when the Packlord sent you here?”

“He never knew about it. The Packlord resides in Orgrimmar, so I was sent back to the city first. Orgnil probably thinks I am still there.”

Mrok’s position was not a unique one. The orcish emphasis on honor, particularly among warriors, is so strong as to largely trump other concerns. While shamans and leaders work to make a Horde a cohesive new entity, the warriors still tend to insularity. This is not to say that the shamans disregard honor; after all, they were the only ones to remember it during the First and Second Wars. Rather, they follow a slightly different concept of honor from the hidebound warriors. They consider loyalty to the Horde, or more specifically the ideals of the new Horde, more important than loyalty to the War-pack.

*********

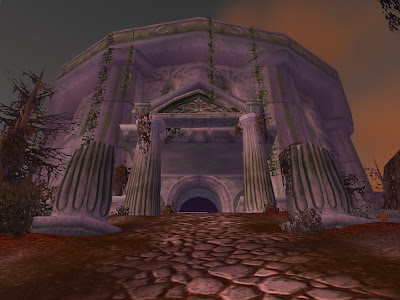

In elder times, Eldarath stood as the jewel of the elven nation. While the capital of Zin-Azshari was larger, Eldarath was unmatched in grace and beauty. Elven arcanists wove magic into art in the city’s age-old gardens and academies. Records tell of intricate and beautiful images hovering in the air, sending lovely thoughts to those who saw them. The elves of Eldarath painted, sang, wore, and wrote magic, and were honored for such.

Almost nothing of that glory remains. The Sundering nearly shattered Eldarath. The land wrenched itself into a new shape, breaking a series of plateaus and staggering drops just above the churning ocean. Temples and palaces split asunder as the ground rose or sank beneath them. Nearly all of the citizenry perished.

Very soon after the Sundering, a band of magic-starved Highborne found the ruins and used the intact enchantments as a source of arcane energy. Their leader was Salferrel Goldenbrow, a dissident noble who took arms against the queen, but found himself in desperate need of magic after the war. Salferrel’s fledgeling kingdom soon collapsed. When the Kaldorei came to stop him he struck back and killed several. His followers were mostly insane at that point, and the Kaldorei had no choice but to slay them all. They arose as magic-suffused specters and have haunted the ruins ever since.

“It’s hard to hear the spirits in this place,” muttered San’drim, a troll shaman.

I was with San’drim and Vald, the latter being an orc warrior. We made up one of the small patrols that Valormok occasionally sent out to Eldarath. Our task was to look for any sign of unusual activity, as well as retrieve any ancient artifacts of significance. Nearly everything worth having was long gone. Salferrel’s elves disenchanted all the magic items they found, so that they could tap into the raw magic within.

For two days we wandered down the deserted avenues of Eldarath, past broken temples and houses. The autumn forest dominates the empty streets, and the colored leaves accentuate the feeling of decay. It is strange to think that such a wondrous city would end up all but forgotten. Of course, Kalimdor is full of such ruins. The remains of Eldarath are larger and, somewhat inexplicably, better preserved than many of the others I saw in Kaldorei lands. The overpowering sense of antiquity stifles any attempt at conversation, the silence almost an active force. Eldarath is one of the most melancholy places I have ever seen. The only remaining magic lies in inscrutable black obelisks that emanate a cold, violet light.

“I think the three of us could easily destroy those ghosts,” said Vald. It was nearing nightfall and we were before the ruins of the main temple. Translucent ghosts hovered in the gateway like an azure fog.

“Best not to deal with the restless dead, Vald. They bring bad luck to everything,” warned San’drim. The shaman then gave me a dark look.

I was starting to regret going on the patrol. San’drim’s attitude towards me could charitably be described as hostile, and I certainly did not trust him to help me in a potentially dangerous situation. Vald, on the other hand, was mostly indifferent to my presence.

“What interest does a Forsaken like you have in this place?” asked Vald, as we made camp one night. San’drim had gone off a ways to speak with the spirits of nature.

“Curiosity.”

“For a dull place like this? It irks me to be here.”

“Why are you here?”

“The elders of Razor Hill vouched for my initiation into the Warsong Outriders, truly an honorable position. I became a brother warrior to them, but one of the shamans said I needed to learn patience, so he sent me up here, far from the field of battle. I feel like I have been dishonored, though I know he had my best interests at heart.”

“You wish to be with your comrades at the front?”

“Of course! Now I fear that they mock me over at the Gulch. I’ve proven my skill with the ax, but no one can know honor unless they have actually fought in battle. At least, that is what my father always said.”

“So your honor has been delayed?”

“My personal honor, maybe. Though going here at the decree of the shamans fulfills pack honor. You wouldn’t know the difference between pack and personal honor, probably.”

“I do not, though I’d be curious to hear it.”

“Pack honor is how a warrior behaves. He brings honor to the war-pack if he fights well. If a warrior does not follow orders, than he dishonors his war-pack. This is also true with how a warrior’s actions reflect on the Horde as a whole. But my honor, that which resides in my heart, are my own victories! One cannot become an Elder unless they have both pack and personal honor.”

“Pack and personal honor can overlap though?”

“Yes. They usually do. But not always. The greatest honor has always been, and will always be, for the fighters! Here, I am a warrior in name only. Some of the great orcish heroes are those who were known more for their personal honor. Even Thrall, in a way, since he was not raised by his clan and forged his own in the form of the Horde. My heart is torn between the two. At times I am sorely tempted to destroy the local satyrs or ghosts, but I restrain myself for the sake of the pack.”

“How long do you have to stay in Azshara?”

“For a few more seasons yet.”

San’drim came ambling back, examining us with a cold look.

“Explaining honor to a dead human, Vald? I don’t know whether to salute your stubbornness or condemn your foolishness,” he chuckled.

“Enough with this, shaman! He cannot help having been a human! And at least he tries to learn of honor.”

“You should be careful, speaking to a shaman that way.”

“San’drim, you are not part of my war-pack. We have our own shamans, who are mighty indeed—”

“And they are not here right now!”

“The spirits are everywhere, and they speak with the shamans of my people! We revere the spirits; you think only of the Loa!”

There was an uncomfortable silence, and I half-feared that the two would come to blows. Then San’drim laughed.

“Finally getting some of that anger out are we? Good, Vald, good! Ha ha ha!”

San’drim sat down at the fire and started gnawing on some dried pork. Vald scowled briefly at him, and then turned to me.

“Would what you just did be personal honor or pack honor?” I asked.

“Personal.”

“You’ve earned it then.”

Vald smiled at that.

The next morning we went farther east, to the cliffs that lead down to the beach called the Shattered Strand. Seagulls wheel endlessly in the air above the ruins, calling out in their hoarse voices. We stood in what had once been a broad thoroughfare that ends abruptly at a precipice. A fierce, briny wind blew in from the Bay of Storms, where dark clouds gathered.

“We may as well turn back after today,” suggested San’drim.

“I agree,” said Vald. “There is nothing here. We’ll inspect any ruins here, and then depart.”

I followed Vald as he went to a ruin near the edge that might have been a gallery of some sort. Then I heard San’drim gasp. Turning around, I saw that he had collapsed to the ground, his head and neck a mass of boiling red welts.

“Vald!” I called. I then turned to the shaman. “What happened?” I demanded.

San’drim could only choke and wheeze. Then a naga slithered out from behind a collapsed wall. Metallic blue scales covered his serpentine form and mottled fins lined his back and arms. A mass of semi-transparent flesh surrounded his right hand, from which hung a mass of tentacles. I realized it was a jellyfish.

Two more naga emerged, carrying more conventional weaponry. Behind me, Vald roared and charged his ax raised high. The blade fell into one of the naga, cleaving through its natural armor. I cast a flame burst on the attacker wielding the jellyfish.

The naga I had burned careened out of the fire, hissing in rage. He lashed out with his arm and the filaments struck me. I felt a slight pain, followed by total numbness. I collapsed helplessly on the ground.

I cannot recall exactly what happened next. My senses became blurred and indistinct. When they returned, I found myself carried between two naga warriors, their scaly hands gripping my feet and arms. They had taken me down to the beach and I dreaded their reasons for doing so. I saw no sign of Vald or San’drim. Around me were the hulking remnants of great temples and palaces, sticking out of the sand and encrusted with barnacles and kelp.

The naga porters stopped and I tried to lift my head. A female naga approached me. Unlike most other sentient races, there is considerable sexual dimorphism among the naga. One can almost mistake them as being two different species. The men are the soldiers and workers of the naga race, and look very much like sea serpents. The women bear a closer resemblance to the Kaldorei they were, though only in the remotest sense. Acting as the priests and sorcerers of the race, the four-armed naga women are clearly the dominant sex.

I heard a symphony of hisses as the naga spoke with each other. The woman then joined the procession. In the distance I could make out a strange pavilion at the water’s edge. A large, elaborate shell was set on the top, indicating naga construction.

They carried me to the ramp leading up to the pavilion. I noticed that shallow waves already flowed over the sands; high tide was coming. Once inside, the naga pushed me down on my knees and placed my arms in green manacles dangling on rusty chains from the roof. I found I could no longer reach the arcane energies of the Twisting Nether.

The naga sorceress slid in front of me. A leash in her scaled hand, she pulled an orc wearing a golden collar around his neck. At first I thought it was Vald, but soon realized he was a different man. Marine parasites covered the orc’s emaciated form. Someone had severed his arms at just below the shoulders, and when he turned to me he revealed wounds in the place of eyes and a nose. His body dressed only in scars, growths of pink coral studded his brow. The sorceress extended her delicate, clawed fingers and inserted the points into the corals. The orc shuddered, and then spoke.

“I am Lady Tsravash, Esteemed Third Daughter of the Fifteenth Family of the Spitelash. I speak through this surface vessel, for I shall not sully my tongue with the orcish speech. Who are you?”

I looked at the orc in horror, and it took me some time to respond.

“I am Destron Allicant. Where are the others I was—”

“I shall tell you only what I deem necessary. But suffice to say that both are dead. You proved surprisingly resilient to the poisons of the sea-sting. Why are you here?”

“I am a scholar.”

“Here? You cannot comprehend our glories, undead, but it is fitting that you would try. You revere the divine even as we revere She Who Will Not Die. Our intent was to kill you, but because you still exist, we shall exact tribute instead. Know you that our sentence is entirely just in light of the crimes your Forsaken have committed against our race.”

“What have we done?”

“They did not tell you of Princess Ezsgajal, First Daughter of the First Family of the Daggerspine? Monstrous! She fell into the uncouth hands of your kin, and they wrought atrocities on her form, destroying the beauty to which countless naga once pledged themselves. The undead ruined her perfection, scarring the flesh and mind of a goddess. Ezsgajal escaped her captors and returned to the deep. We destroyed her in our mercy. That which was glorious should not be remembered through that which is base.”

The tide crashed over the dais of the pavilion. I wondered if I was meant to drown there. The Forsaken can get by with very little air, but they do need some. Death would be a prolonged and painful affair in such an event.

“It comes,” cried the orc, his ruined face twisted in dread as he spoke Tsravash’s words. “The Leviathan comes, bringing the warriors of the deep. The Abyss grants the surface her own children, to destroy its corruption.”

No sooner had the orc gone silent when the pavilion began to shake. Tsravash raised her two left arms and turned away from me, letting out a haunting wail. The shaking grew worse, and then the seas split as a great worm burst forth from the brine. Ripples of iridescent blue flesh veiled the organs beneath, and its cavernous maw opened wide. The worm let out a long and terrible roar that shook the heavens before beaching itself with a thunderous crash, sending huge waves across the shore.

I was knee deep in water while Tsravash sung her eerie call and the orc wept. A strange seaweed covered much of the worm, the stems ending in leaves or pods. The weed colonies slowly fanned out from the body. Naga warriors emerged from the pods, as if hatching from eggs, two in each. A terrible chorus of hissing filled the salty air as the naga beheld the ruins of the city they once adored. Tsravash’s voice fell into silence, and she turned back to me.

“This is but one army of our empire. Count yourself blessed to have witnessed this event. You will be taken to Nazjatar, the Idyll of the Deep. There you shall suffer the agonies of Ezsgajal rendered ten-fold upon you. Your deadened senses will not preserve you there. We have had millennia to perfect the arts of cruelty. Before you go, there is something I must do. Your surface-dweller’s gaze would corrupt Nazjatar. As we cannot remove your sight, we shall prevent you from seeing.”

A naga warrior approached me and slapped a wet kelp leaf over my eye sockets. Then I felt a pricking sensation on my brow, and I realized the leaf was being sown into my face. Blinded, my guards opened the shackles and dragged me from the pavilion. All around me I heard the endless hissing of the naga, punctuated by guttural croaks. The feeling of the sun on my back vanished as they pushed me into frigid darkness, a chamber partially filled with seawater. My captors encased my hands within some kind of sponge-like material before they released me. I sank until only my head and neck remained above water. The hissing ceased, and I heard only the slosh of water. I was still unable to cast spells, and with no other option I stoically resigned myself to oblivion. I could only hope that Tsravash had exaggerated the skill of the naga torturers.

*********

I awoke into darkness; lying on cold, damp sand. I heard the call of seabirds somewhere above me. I realized that my hands were free, and I quickly undid the stitching of my blindfold.

I sat on a desolate beach stretching below the wind-scoured cliffs. A bitter wind blew in from the east, carrying a salty tang. I conjured up some food and water and wolfed them both down. After finishing, I looked up and found myself staring into the eyes of a murloc.

I almost attacked it with a spell before I realized it had not made any hostile action. I slowly got to my feet. Looking around, I saw a large number of murlocs on the beach. The one in front of me gave a weird little cry, and then pointed to the ruins of a great temple rising from the choppy waters. The murloc again raised its pale, elongated hands in the direction of the temple. Feeling uncertain but finding no other option, I crossed the rocky beach towards the temple. My backpack was gone, presumably taken by the naga. However, my most vital gear (the photo-recorder and the disguise) had been on my person, and were untouched. Clearly, I had much reason to be thankful.

Three giant lobster-creatures stood on the great ramp leading to the entrance. They examined me with eyes placed at the end of stalks, and stood aside to let me pass. I recalled hearing mariner’s stories about arthropod creatures living on the coasts of Kalimdor. The sailors called them either makrura or lobstrok. I wondered if the entity before me was one of their number. Most stories portray the makrura as territorial and vicious, though the ones before me made no attempt to attack. Then again, considering that the murlocs had behaved with similar courtesy, I was not necessarily dealing with normal representatives of the race.

An impossible twilight jungle thrives in the temple’s interior. Vines cover the walls, and thick trees grow from the floor. Greenery also fills the Temple of the Moon in Darnassus, but there it is carefully tended. The garden in Azshara is wild, and has been for a long time. Murlocs and makrura wander the interior, the two races usually keeping their distance. A pool of murky water lies in the center, presumably the remnants of a moonwell.

At the other end is a spiraling ramp that leads to the temple mezzanine. I ascended it, not without trepidation. Though no move had been made against me, I suspected I was in the presence of something strange and powerful.

The mezzanine is similarly overgrown. Through the vines I saw a towering giant standing on the balcony, his skin turquoise and his face partly hidden by a sea-green beard. Even in the distance I could see his eyes (which were huge sapphires) as they fixed upon me.

“Come to me,” he said. The words were complex and utterly foreign, yet the meaning resounded clearly in my mind. Though his voice was calm, there was no mistaking the authority in his statement.

Getting closer, I saw his massive form garbed in the refuse of the sea. Barnacles and anemones grew on his arms and legs, and he wore a tunic of kelp. Incredibly, I saw tiny fish darting to and fro between the strands of vegetation that he wore, though he was not in the water.

“I am Arkkoroc, the Keeper of the Tides. Do you know me?” he inquired, in a slow and rumbling voice.

“I regret to say that I do not.”

Arkkoroc gave a deep sigh.

“It is as I feared. Who are you?”

“I am Destron Allicant. Did you save me from the naga?”

“My children did. It has been many centuries since I have last seen one of the surface races, and my children know that I have interest in them. They slew the leviathan, found you, and brought you to this forgotten place.”

“You have my thanks.”

“You, Destron, are certain that you have never heard the name Arkkoroc?”

“I am. Please, tell me who you are.”

“I am the Keeper of the Tides. A long time ago, thousands of years ago, the shapers formed me from the earth and charged me with watching the tides. I did this for eons, and was happy. The trolls and elves both acknowledged me. Though I was neither an Ancient nor a Loa, they respected my power. Supplications were delivered unto me by those who traveled the ocean.”

“This temple was dedicated to you?”

“No. This land was not always by the sea. After the Sundering, I moved here. I thought the surface races might have need of me. Few ever asked for aid. In time, none did. I have not heard my name spoken in so long...” he trailed off.

“Who are the shapers of which you speak?”

“They are the Titans, who ordered this world. Destron, you must remember me. Tell the mortal races that I still live. Promise me this, and I shall aid you.”

“Very well. It is the least I could do as repayment. I should tell you though, that the mortal races all have their own beliefs. I cannot guarantee they will embrace a new god.”

“I no longer care if I am worshipped. My only care is that I not be forgotten. Tell others that I exist. Tell others that their fathers worshipped me.”

“Of course. What of the murlocs here? Are they not worshippers?”

“They know I have power, and they are drawn to me as a result. Normally they are quite savage, but I have calmed them for the time being. But do not stay for long, as I can only control them for a short while.”

“Were they the children of which you spoke?”

“My children are the lesser giants who dwell beneath the waves. They bear great hatred for the naga, and for most surface-dwellers as well.”

“Of course. I do not mean to be impudent, but may I ask a favor of you?”

“You may ask.”

“I have friends in a place called Valormok, a ways inland. I must inform them of the naga presence.”

“The naga are unlikely to attack them, but I shall grant your request.”

“Also tell them that San’drim and Vald both died in an ambush, and that Vald fought with valor and honor. Do you know where Valormok is located?”

“I shall bind together the spirits of sea and sky; the sea does not know, but the sky knows almost all.”

Arkkoroc raised his mighty hands. A liquid sphere manifested between them and gradually took the shape of an albatross made of water. Arkkoroc said something to it in a strange language, and the bird flew out of the temple.

“That will relay my message?”

“It shall. You will also require transport to leave this place. We are quite far from all things.”

Arkkoroc again raised his hands. At first there was nothing. Then I saw that a great tendril of water slowly raise itself from the pool on the temple floor. Soon it reached the mezzanine and hovered before me.

“This is the Path. It will take you to a marsh, far to the south. I do not know what the mortals call this land.”

I reasoned that he probably meant Dustwallow Marsh.

“I think I know the place of which you speak. May I request that I be sent to a red desert, just to the south?”

I was referring to Durotar. Arkkoroc shook his massive head, the movement of his beard startling the fish in his tunic.

“There are strange spirits there. Though not wicked, they are alien to me. The coast of the swamp has many mortals, and I recognize the spiritual presence there, if only vaguely.”

“Very well. Give me a moment.”

As I would be landing on or near Theramore Isle, I deemed it prudent to put on my disguise. The powder that masked the smell of death was soaked but still usable. With that done, I faced the floating pillar of water next to the balcony.

“How long will it take?”

“Less than a day.”

“What about breathing?”

“There will be air for you. Destron, even if you do not tell others that I live, please at least remember me.”

“Lord Arkkoroc, I do not think I would be able to forget you even if I wished to do so. You have helped me a great deal, and I thank you for it.”

I swam into the water. The interior of the liquid drained, until I floated in a free-floating tunnel of water. Then came the mighty force of a thousand tides at my back, propelling me forward into the unknown.

In the paragraph

ReplyDelete"As I got closer I saw that he the refuse of the sea covering his body. Barnacles and anemones grew on his arms and legs, and he wore a tunic of kelp",

the first sentence is missing "had":

"As I got closer I saw that he had the refuse of the sea covering his body. Barnacles and anemones grew on his arms and legs, and he wore a tunic of kelp"

Thanks. I actually ended up changing the entire sentence, since the original sounded a bit awkward. It now reads:

ReplyDelete"Getting closer, I saw his massive form garbed in the refuse of the sea."

This one was really cool.

ReplyDelete