I descended the mountain pass into a land of otherworldly splendor where the air wraps around the traveler like a hot sponge. Thousands of spectral lantern lights gleam within fungal bodies, lighting the dense fog. Vapor clouds churn endlessly in the murky skies.

Azeroth’s Eastern Plaguelands has a mushroom forest of its own, but it’s nothing more than a foul parody of this alien swamp. Zangarmarsh is a place of overflowing life, a primordial land that exists beyond imagination. Great mushrooms, some reaching as high as Feralas’ giant trees, grow from the swampy floor. Soft lichens and glowing caps cover the ground in a blanket of dark colors. Clouds of glittering spores lazily float through the air like fairy dust.

While much of Outland still reels from the scars of demonic invasion, Zangarmarsh remains vibrant. It was a perfect sanctuary for the draenei. Few orcs were familiar with Zangarmarsh, and the Horde’s impatience made a thorough search of the region an impossibility. Demon armies did march through the swamps after the Breaking, but they moved directly to Shadowmoon Valley. The relentless marsh quickly reclaimed the land they tainted.

I stood in the drizzle for what must have been hours, the water an indescribable deliverance from the parched air of Hellfire Peninsula. I detested humidity while alive, but it’s nothing more than a mild irritant in undeath.

I entered Cenarion Refuge in an ebullient mood. Built on the Zangarmarsh’s eastern edge, the town acts as a base for the Cenarion Circle in Outland. The Circle was one of the first groups to cross over, the druids eager to repair Draenor’s ecology. Some in Nighthaven and Darnassus criticized the Outland druids, arguing that Azeroth’s very real problems should get first priority. Archdruid Fandral Staghelm steadfastly refused to lend any aid to the Outland efforts. Because only a slim majority of the Circle promotes the Outland reclamation campaign, the Outland druids are considered a distinct but subordinate division called the Cenarion Expedition.

The Cenarion Refuge is basically a night elf town transplanted to Outland. The gleaming waters of a Moonwell spread their light at the camp’s perimeter and a leafy ancient keeps a watchful eye for intruders. I saw elven and tauren druids arguing around a cluster of azure-capped mushroom growing on the Moonwell’s rim.

I went to a large wooden hall built on a massive stone foundation. Three Kaldorei worked on the roof, scraping off fungal blooms growing on the eave. A tauren brave, wearing the armor of a Cenarion Warden, leaned against a rail by the entrance. He flinched when he saw me, but quickly regained his composure.

“My apologies, Forsaken ally. My mind was wandering.” His voice sounded quite tired, probably because of the heat.

“You needn’t apologize. Are visitors welcome in Cenarion Refuge?”

“As long as they do not hold the Expedition as an enemy.”

Sensing he wasn’t in the mood for conversation, I thanked him and went inside. The interior was almost painfully bright, as if overcompensating for the dimness outside. Travelers from various races rested on soft mats laid out on the floor.

“Say, by any chance do you have a mushroom problem in Undercity?” asked a night elf, speaking in awkward Orcish.

“There’s a great deal of mold but no one seems to care about it. Why do you ask?”

“The swamp keeps trying to take over Cenarion Refuge. The druids are having a bit of trouble working with it. They say it’s because they’re dealing with an alien world with a very strange ecology. Did you notice the workers up on the roof?”

“I did.”

“They go up there every few days. The wood in Kaldorei buildings is still alive, so it heals itself, but only as long as we scrape off the mushrooms first!”

The elf introduced himself as Marin Moonroot. His stories suggested that the living races weren’t enjoying Zangarmarsh as much as I.

“There’s been much confusion. I hate to sound petulant, but the expedition can’t seem to decide on a role in Zangarmarsh. Tauren and elf alike are driven half-mad by the humidity. The tauren also thought we should build Cenarion Refuge out of indigenous materials. The elves figured it’d be fine to bring in a foreign seed, so long as the druids made sure it couldn’t reproduce, which they did. Unfortunately, the mushrooms seem determined to grow on every wooden surface.”

“You said the tauren wanted to build using local materials. How do you build structures out of fungus?”

“Oh, I’m not really sure. You should probably ask one of the druids.”

Taking his advice, I met with a druidess named Heyemah Windtotem. Though exhausted by the heat, she bore it with good grace. We spoke next to the moonwell, where fungal tendrils gripped the stony rim.

“Ah, Zangarmarsh is still a great mystery. The spirits here do not give up their secrets easily. Still, we are learning. To answer your question: the great big mushrooms, called zangarstalks, have all kinds of uses. They start off small but quickly grow. At first, a zangarstalk is encapsulated in a white ball called the universal veil.”

“I’ve seen these in Azerothian mushrooms.”

“The principle’s the same, just on a bigger scale. Zangarstalk veils are like leather or hide, and can be used for canvas. Anyway, the mushroom eventually breaks the veil. As it grows, it develops a very hard sheath that encircles the stalk and the underside of the cap. This sheath is as strong as wood. The Alliance Expeditionary Force made buildings out of it!”

“Wouldn’t the mushrooms become extremely heavy?”

“The flesh of the fungus is full of air sacs, which keep it light. Sometimes the zangarstalks fill up with water, which causes them to collapse. In these cases, the bottom of the mushroom bursts and the rest topples. That’s why we periodically drain the zangarstalks around the refuge. If they collapse here, people could die.”

“Where do the zangarstalks get their sustenance?”

“Orcish legends say that a terrible and wicked giant lived here until he was slain by one of their heroes. The mushrooms sprouted from his rotting corpse.”

“You think this is true?”

“It is not for me to question the wisdom of the orcish ancestors,” she shrugged. I was not quite satisfied by her answer, but no one else could offer a more concrete explanation. One answer is that the zangarstalks grow on the rotting bodies of older, dying mushrooms. Even the druids acknowledged that these alone could not account for the zangarstalk’s gargantuan size.

Cenarion Refuge seems incongruously busy for an elven-tauren settlement devoted to the preservation of nature. This is because of the very real difficulties faced by the expedition. The fruit trees usually grown by the Kaldorei simply can’t survive in Zangarmarsh. This is not to say that food is hard to find; there are scores of edible mushroom species. The elven druids merely dislike the hassle of having to gather these mushrooms, as they cannot yet grow them with their powers.

“In truth, I am a bit troubled. I am not sure that all the Kaldorei here really understand that we are in an alien world. Cenarius never walked these swamps. I’m not sure if his powers really apply here.” I was speaking with a venerable elven druid named Delendius Nightwhisper. Less bothered by the humidity than most, he spent his free time in a mushroom copse at the town’s edge.

“I’ve seen druids here shapechange and use other abilities. They don’t seem to be having any trouble.”

“Our individual powers remain unaffected. Yet interacting with the local environment is very difficult. Were this Azeroth, we’d have established a much larger colony of living buildings by now. The marsh fights us every step of the way.”

“Do you think the problem lies in using Azerothian seeds to grow the buildings?”

“I believe so, yes. The druids must earn the trust of nature in Outland. This ecology does not yet know us as protectors.”

Cenarion Refuge does provide an interesting perspective on the different attitudes towards nature held by the night elves and tauren. The elves, who have long served as nature’s special guardians, have a paternalistic view of the ecology. No reasonable person would doubt the sincerity of their devotion, but they clearly expect nature to conform to their standards.

In contrast, this first generation of tauren druids grew up as hunters in a vast and often fearsome wilderness. They see nature as the master and believe it will ultimately survive with or without druidism. Obviously, this ties into preexisting tauren religious beliefs. I believe this is why the tauren seem less bothered by the fungal incursions. It’s more or less how they expect nature to behave. Even so, not all of the advantages go to the tauren. The Shu’halo are much more adversely affected by the humidity than are the elves.

The druids arguing over the fungal presence in the moonwell decided to let it stay. I think it was a wise choice on their part, an opinion shared by the majority of the Cenarion Expedition. A cluster of glass-cup mushrooms now thrives in the sacred pool. Egg-shaped with open tops, the texture resembles veined glass. Glass-cups are large, each about the size of a gnome. Rain falls into their open bodies and quickly spills over the brim, making them look like overfull wine glasses. They are common enough in the swamp, growing together to create natural fountainheads.

Delendius acted as my guide in Cenarion Refuge. He had been a druid since before the Sundering and was greatly respected for his wisdom. A preference for animal form and a lack of ambition kept him from rising high in the Cenarion Circle. Delendius joined the Cenarion Expedition to get away from the Azerothian politics he detested. Unlike many druids, he was not bothered by my undeath.

“In my time, I’ve seen our great queen consort with demons, survived the Sundering, waged war with insect monstrosities, and watched as Nordrassil died. Forgive me if I sound jaded, but an ambulatory corpse doesn’t strike me as all that remarkable,” he joked.

Delendius’ passion lay in observing the bizarre animals of Zangarmarsh. Many of these creatures are actually mobile fungi. Such a find is rather incredible, even by Outland’s standards.

One species is called the sporebat. These fungal beasts swim through the air with an almost languorous insouciance, supported by lines of subcutaneous ventral air bladders. The form vaguely resembles that of a manta ray. The most notable feature are the eerie lights that radiate from within the sporebat’s body. The brightest lights lie at the tips of the posterior tendrils.

“Why do they glow like that?” I asked.

“Phosphorescence seems to be a common trait in Zangarmarsh. The sporebats come out at night, which is why we named them after bats.”

“They’re beautiful creatures. What do they eat?”

“Mushrooms. There’s not much else to eat here.”

At that moment, one of the glowing bats drifted towards us. Slowly swishing around in the air, it studied us with glowing eyes (assuming that those lights really were eyes). The creature’s seeming curiosity worked to anthropomorphize it. The interplay of spectral lights in its body was nearly hypnotic. Delendius smiled at the creature, which stayed for a few minutes longer before flying away into the marsh.

*********

Black eyes lit up when I spoke. Sull’s skin, pitted and wrinkled from years of hardship, stretched tightly over his skull. He examined me for almost a minute before responding.

“Forgive my rudeness,” he wheezed. “I sometimes forget where I am. What is your name?”

“Destron Allicant. Delendius told me that you acted as an unofficial liaison with the Lost Ones. I’m trying to learn as much about this world as possible. Do you think you could take me to one of their villages?”

“Hmm, Umbrafen Village is safe enough I suppose. The madness is not as deeply rooted there as it is elsewhere in the swamps. It’s a hard journey; are you sure you would be up for it? Many from your world are not.”

“I’ll manage.”

“Very well. Tomorrow morning then?”

“That would be fine.”

I thanked Sull and returned to the inn. Sull was of that tragic breed called the Lost Ones. These unfortunates are draenei who degraded even further than the Broken. Remembering nothing of their past lives, they congregate in remote parts of Outland. Their erratic behavior furthered their isolation; while often peaceable, Lost One militias occasionally go on the warpath and kill all that they see. It was not my first encounter with the Lost Ones. I’d run across a few back in the Swamp of Sorrows.

Delendius said that only the Umbrafen tribe seemed at all interested in coexistence. Sull had guided a few druids to Umbrafen Village in the past, though the Cenarion Expedition could make no headway in healing the Lost Ones. Even the draenei, who strived to redeem their Broken kindred, largely avoided them. Only those few Lost Ones who actively seek help, such as Sull, ever receive it.

We left early the next morning. Waxy orange light glowed dimly on the fungal bodies encompassing us, obscured by sheets of warm rain. Sull stood next to his tent, stick-thin legs barely supporting his hunched figure. Appearances can be deceiving. In spite of his distorted physique, Sull moved quickly and agilely through the marsh and I struggled to keep up with him.

Days passed in the mist and rain, our way lit by the soft fungal lambency. We rested during the night, usually eating local mushrooms. Since we were only a Lost One and a Forsaken, we did not bother with tents. On the way, he told me of Zangarmarsh’s recent history, and of the Lost Ones.

“The Pure Ones, whom you call the draenei, say I was once like them. In truth, I do not remember. None of us do. All I can remember is the marsh.”

“Was Sull the name you bore as a draenei?” I asked. We were camped by the waters of Umbrafen Lake, the rain drumming its surface.

“Perhaps. As far as I can remember, Sull has always been my name. Sometimes I like to think my name was Vuunos. That is a good name. There is a draenei priest named Vuunos in Telredor, who visits Cenarion Refuge. He is very kind to me.”

I wasn’t entirely sure what to make of this.

“But your name was not Vuunos?”

“Everything behind me is blank. I can fill it with whatever I please. Many Lost Ones do, and some entirely believe it. But I know that my name was probably not Vuunos.”

“Do your people have any contact with other Outland races?”

“Only the ones that Vuunos calls the Broken. They made contact with us, though we did not wish it. Many Broken lived here in Zangarmarsh. The Wrekt Tribe, they called themselves.”

Sull’s face distorted into a scowl.

“The Wrekt! Their warriors came to our village, swamp spirits at their beck and call. They said that the spirits demanded blood. Nothing but blood would appease them. So of course, these Wrekt, they say that the blood of Lost Ones will nurture the spirits.”

“They sacrificed Lost Ones?”

“The Wrekt gutted us in our villages, tore us to pieces. But what could we Umbrafen do? They were too great for us to resist. The Wrekt took some of us prisoner and put us to work. The elevated roads we walk right now, how do you think they got there? My people bled for them. The Wrekt wanted to make their little empire. The Mistfen and Hungerfen, two tribes of Lost Ones—completely wiped out!’

“Did you fight back?”

“We could not gather our senses together. At times, great rages seize the entire tribe, but we have no control over it. Lost Ones are poor fighters. Poor in everything!” he spat.

“What happened to the Wrekt?”

“I do not know. Their warriors used to appear every month. One month, they simply stopped.”

“Did the Wrekt have any enemies? Or allies, for that matter?”

“I do not know much of the world beyond the swamp. There was a tribe of Broken to the east, the Dreghood, and they were friends with the Wrekt. Yet I only saw a few Dreghood here. The Pure Ones did nothing to help us. They said they were too busy hiding from the orcs. No orc ever hurt me, as far as I remember. Only the Broken hurt me.”

Days of travel in rain and fog at last brought us to the moldering hovels of Umbrafen Village. These huts are made from sheets of universal veil, supported by rickety frameworks of zangarstalk bark planks. Each is placed on stilts as a precaution against flooding. Sagging under the perpetual drizzle, they hardly inspire confidence.

Umbrafen Village is the perfect image of neglect. I mentally compared the place to the Harborage, that tiny hamlet of exiled draenei back on Azeroth. The Harborage’s populace had been devastated by the experiences of genocide and exile. Yet even they managed to sustain some level of cleanliness in their village. Though they sang hymns whose true meaning was lost to them, such rituals at least brought them together.

In contrast, heaps of decaying rubbish threaten to overwhelm the village. The huts lead out into shallow pools of filthy water. Only the barest effort is made to make the place livable. The draenei describe Magtoor’s folk as stuck in a transitory point between Broken and Lost One. The Umbrafen were my first experience with those who had gone all the way.

“We made the village in the early days of our curse. Since then, it has decayed. It is hard to build things. Our minds cannot stay on task,” explained Sull.

I soon spotted the Umbrafen villagers. Most sat in the mud surrounded by sodden junk. Scraps of universal veil hang loose on their wrinkled bodies. They said nothing as we passed by. I remembered my time in the Exodar, where I had been graciously welcomed even though I was a total stranger. The Lost Ones didn’t even seem to look after their own.

Sull splashed down into a muddy pond filled with floating debris. Three sagging huts loomed over the pond. Sull pointed to one, saying it was his home. I cautiously followed him up the water-logged ramp to a small and dark room completely lacking in furnishings. It was not devoid of life; countless tiny white mushrooms grow from the floor.

“How long has it been since you were last here?” I asked. While I was no stranger to poor accommodations, the village’s miserable state was more indicative of madness than of poverty. Granted, Sull had the excuse of a lengthy absence, but my walk through the village suggested that the other homes were no better.

“I am not sure. A long time.”

“Why did no one welcome you back?”

“They did not care.”

“There’s no tribal community?”

“We are the Lost. Isolation is our fate. We think only of half-formed memories, delusions, and hatreds. The Umbrafen stay together for protection, not for comfort. There are no friends in the tribe.”

Doubtless tired from his long journey, Sull lay down on the blackened floor and instantly fell asleep. I sat by the entrance through the night. Sull’s neighbors never came to visit. Even my alien presence failed to spark their curiosity. I could not fathom how such a society might survive.

I accompanied Sull when he went outside for breakfast the next morning. Ambling over to a nearby zangarstalk, he tore off a brown polypore growing on its side. He plopped down in the mud and began to eat it.

“Do the Umbrafen eat anything other than mushrooms?”

Sull made a strange sound, which I realized was a laugh.

“Not really. The Lost Ones cannot hunt or make farms. A few of us fish, but they only do so to feed themselves. Plenty of mushrooms though. Zangarmarsh indulges our madness. Food is never an issue here. If it were, we’d have all died.”

In the distance I noticed a curious structure in the middle of a stream. A wooden dome sat in the water, supporting an apparatus of veil sheets. The sluggish current turned the sheets, like a crude water mill. I did not know why they would need a mill if they lacked agriculture.

“What is that then? It looks like it took a great deal of effort to build,” I said.

“The spirit taps? Those were not of our making. The Wrekt built them. Their hope was that the spirit taps would capture the entities of water and air, letting the shamans control them.”

“Did it work?”

“No, it failed. Vuunos tells me that the Pure shamans speak with the spirits and bargain with them. The Broken want domination, to use the spirits as tools.”

I recalled the Dreghood Broken in Telhamat, who said that the spirits had turned against his people for that reason. The Dreghood had learned from their mistake, but the lesson was lost on the Wrekt.

“Clearly you hate the Wrekt. Is this sentiment shared by other Umbrafen?”

“All of us hate the Broken. Not just the Wrekt, all Broken. Vuunos says hatred destroys the spirit. But hate is the only spirit I have!”

“Are the Umbrafen united by hate?”

“Perhaps we are. The Lost Ones lie in filth, and care not for the outside world. Only when the outside comes to us, bearing iron and flame, are we roused. Should I not hate? I do not know. We Lost Ones ask for nothing yet the Broken kill us just the same.”

Sull’s mannerisms became wilder and more animated. I tried to calm him down, while thinking over what he said. The draenei said that fel exposure tainted the souls of many Broken, leading them to favor wickedness. The Lost Ones had taken it even further. Largely empty of any real desire beyond bare survival, only negative emotions animated them.

Sull fell silent after venting his rage. Finishing his meal, he took dejected steps back to his hut.

“How could we have ever felt otherwise? This Vuunos does not understand. Maybe he lies when he says that Lost One and Pure One are related?”

“Vuunos speaks the truth, Sull.”

“So you say.”

Communication with the other Lost Ones proved nearly impossible. The Lost Ones speak an altered form of Eredun, filled with Orcish loan words. Their accents are thick, and they slur each letter. I had to content myself with observation, but there was little to see.

A family of Lost Ones lived in the hut opposite of Sull’s. Perhaps family is not the right word, for they seemed indifferent to each other. A pair of Lost One children sat on the ramp. They never played or even spoke. I couldn’t really tell how old they were, though judging from the size I figured that they were probably around ten years of age. An adult with a missing leg lay sprawled in the hut’s interior. Male and female Lost Ones look quite similar, so I could not tell whether the adult was the mother or father.

Sull left his hut and joined me in the evening, as a heavy mist obscured all but the brightest mushroom lights. I felt quite depressed, and was about ready to go back to Cenarion Refuge. Sull apologized for his earlier outburst.

“That is Vin over there, and his two children,” he said, pointing to the family I’d been observing. The children had gone back inside.

“Who is the mother?”

“Vin’s mate was Seda. She is with another.”

“Marriages are not permanent?”

“There are no marriages. We do not love.”

“Doesn’t the mother take care of the infant?”

“At first. I think, in a child’s first year, love may exist between it and the mother, but only then. After that it fades, and both go their own ways. Survival here is easy. A Lost One reaches adulthood in three years; much faster than the Pure Ones.”

“That’s the only interpersonal bond?”

“I think so. Those children will leave Vin in another year, at most. Do you see why I spend my time in Cenarion Refuge? I do not know the things they do there, but something in their souls is stronger. I feel less empty when I am with them.”

“Sull, I am very sorry for asking you to take me here. You should have told me. I don’t want you to suffer like this.”

He looked puzzled.

“Are you suffering?”

“Some. I think the suffering around me is causing that.”

“Hmm, just like the Pure Ones say. It is hard for me to imagine that you care. Perhaps you are only pretending.”

“I assure you that I am sincere.”

“Maybe. We will leave tomorrow.”

The Lost Ones were like draenei that had abandoned everything, keeping only that which was necessary for basic physical survival. The Umbrafen mental state proves that sapient beings need more than food and water. Community of some sort is equally necessary. The Lost Ones have no love, no ambitions, no hope, and no morals. I doubt they can survive for very long, even in the plenitude of Zangarmarsh. Apathy will eventually consume them.

Enraged shouts from outside Sull's hut broke my slumber. A lone voice yelled at first, though others soon joined it. I suddenly noticed Sull roaring, his mouth a black and bloody pit. He scrambled outside on his knees and I followed, readying a spell.

A pair of Lost Ones stood in the central pond. Bright motes of lightning orbited their bloated figures. I recognized the phenomenon as the lightning shield used by shamans. The electric glare revealed the net bundles on their backs, packed with bones and fungal husks. The two shamans flailed their arms. One of them held a wooden pole topped with a burning skull.

Umbrafen villagers stood all around, raising their spindly arms and crying in tones of fury. Then it stopped. The fire in the skull died, and the shamans wandered away. The Lost Ones returned to their homes. Sull’s body relaxed and I turned to him.

“What happened?” I demanded.

“The shamans did their rituals.”

“I didn’t know the Umbrafen had shamans.”

“We learned from the Wrekt. The Lost Ones could always hear the voices of the swamp, but we could not understand them. Our shamans are mad. Vuunos believes that they actually taint the spirits with their minds.”

“The Wrekt taught this to the Umbrafen?”

“I think they wanted to use Lost One shamans as weapons. They had many uses for us. I am sorry if that disturbed you. The madness of the shamans is spread to us when they are near.”

“You needn’t apologize.”

I was almost desperate to leave Umbrafen Village. Zangarmarsh, which once seemed so beautiful, became menacing and ineffably alien. The mentality of the Lost One is not really so different from the psyches of some Forsaken. I feared that spending too much time with the Umbrafen would make me like those I'd sought to escape.

We left in the early morning, the swamp mists lit by an unseen sun. I walked as quickly as the treacherous marsh would allow, badly wanting to be away from the rotting village. I suspected that Sull was also eager to depart, and I regretted asking him to return. I noticed movement in the distance as we traveled. Distorted Lost One silhouettes marched alongside us in the fog. Worried, I asked Sull if he noticed it.

“I see them. I do not know what could rouse them like this.”

“Are they following us?”

“No. Some have already passed us by. I think they are headed in the same direction as us though.”

Perturbed, I continued following Sull. A pack of five shabby Lost Ones fell into step besides us. Sull began speaking with the Lost One in front. They talked for a while before Sull turned to me with an explanation.

“The Wrekt and the Dreghood! They are slaves now! Just as they turned we Lost Ones into slaves, a greater power has made them into slaves!” exulted Sull.

“What is this greater power?”

“They killed many of the Wrekt and enslaved the survivors. Truly this is glorious! A race of serpent warriors conquered them.”

I realized, in grim certainty, that the serpent warriors were none other than the naga. The naga had allied with Illidan, and sent many of their kind to Outland. Zangarmarsh is really the only region in Outland compatible with naga physiology.

“Sull, you must listen to me. The naga are wicked. They are the enemies of your friends in Cenarion Refuge!”

My words were lost on him. A hideous glee spread through the Umbrafen gestalt and the ragged figures around me cavorted and cheered. Spore-encrusted faces broke into terrible smiles. Sull was completely beyond caring what I said, and I knew that my only choice was to flee.

I tried to force my way out of the mob, even as the multitudes pushed me forward. They arrived at the Broken prisoners before I escaped. The shouts of the Lost Ones drowned out all other sound. Bound hand and foot, the Broken were completely helpless.

Sull broke to the front of the crowd, howling as he went. Reaching one of the slaves he flailed at the Broken’s face. The slave cried out in pain, trying to dodge the blows. More Lost Ones joined the fray.

I finally forced my way out of the mob. I had seen what the naga did to their prisoners, and I was determined to escape. Bright flashes punctuated the mist and the crowd abruptly fell silent, the shouts melting into gibberish chants from a trio of shamans. The shamans raised their totems above their heads, their bodies jerking and contorting in pain. The Umbrafen laypeople retreated as the shamans approached the Broken. The fog hissed, heralding the arrival of the naga.

I did not look back as I fled to the north.

*********

It was with a heavy heart that I described my sojourn in Umbrafen Village to Ysiel Windsinger. Ysiel was the leader of the Cenarion Expedition, and she took a keen interest in news from around Outland. As one of the most articulate proponents of healing Outland, she was a natural choice for leading the Expedition.

“We received reports of naga activity just a few days after you left. I do not know what they want from Zangarmarsh, but it cannot be anything good.”

“I am sorry that Sull did not return. I have no idea what happened to him.”

“You are not at fault, Destron. Sull made his own choice. You say that the naga use the Broken as slaves?”

“That’s what Sull told me. I do not think he knew of the alliance between naga and Lost One prior to our arrival.”

“Why didn’t the naga enslave the Lost Ones?” mused Ysiel.

“The Broken are in better physical and mental condition than the Lost Ones. I suspect that the Wrekt only used the Lost Ones as slaves for a lack of alternatives.”

“That makes sense.”

Cenarion Refuge had been busy in my absence. A quintet of volunteers had journeyed east to investigate the impact I witnessed in Hellfire Peninsula. More controversial were the actions of one Terserion Shadeleaf. Terserion was an old druid known for erratic behavior. Somehow, he’d gotten the idea that the Lost Ones would benefit from learning druidism. Ignoring Ysiel’s orders, he marched off to teach the reclusive Feralfen Tribe. None knew what had become of him since then.

The Feralfen Tribe itself is something of a curiosity. Though generally hostile to outsiders, draenic reports suggested a much stronger community than what I saw in Umbrafen. Lost One shamans seem to have great psychic influence on the rest of their tribe. Thus, if the Feralfen shamans are more rational than the Umbrafen, it may result in a stronger tribe.

My next stop would be the draenic sanctuary of Telredor. I’d heard of the place while in the Exodar. I first thought the draenei were joking when they said that Telredor was built on top of a giant mushroom, though I soon learned that such things are far from impossible in Outland. I also hoped that the draenei could give me a more objective viewpoint of the conflict between the Broken and the Lost Ones.

I felt my spirits rise as I traveled. The wretched squalor of Umbrafen Village receded into memory, and I again appreciated the swamp’s surreal elegance. The elevated roads leading to Telredor had been recently built by the draenei (as opposed to Lost One slaves), and remained in good condition. As such, it took only three days to reach Telredor. Needless to say, I prepared my human disguise.

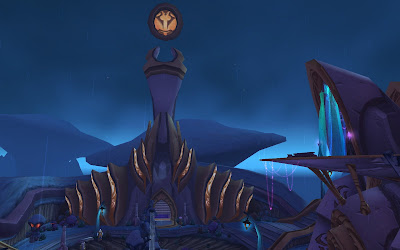

The Telredor zangarstalk rises high above the surrounding murk. As I got closer I saw lamp-lit walkways and structures clinging to the stem. Large though it was, I knew it wasn’t big enough to have sheltered the entirety of the unmutated draenic population.

The road ended at a raised sanaum platform facing away from Telredor. Next to it was an engraved metal plaque with two messages, one written in Eredun and the other in Common. It read:

“The people of Telredor are glad to welcome you, fellow traveler in the Most Holy Light. To gain access, simply stand on the platform to your right. It is enchanted, and shall lift you to Telredor proper.”

Shrugging, I did as the message suggested. Sure enough, the platform disengaged, moved back a few feet, and ascended into the air. The platform ascended above the rim of the mushroom cap, and I glimpsed the polished towers of Telredor. The ascent stopped and moved forward to a ledge built into the cap’s side. Two draenic guards stood at the ledge, and waved when they saw me.

“Welcome to Telredor, Brother Human!” beamed one. “I am Lorus and my companion here is Nataar,” he said, pointing to the other guard. Nataar nodded in acknowledgement.

“Thank you, Lorus. My name is Talus Corestiam; I’m an itinerant mage and scholar. I’m hoping to learn more about draenic history here.”

“Telredor is a good place for learning! We stored our records here while we recovered from the orcish attacks. Many of those records went to Shattrath, but some remain. Please, follow me. Our guests typically stay in the temple though I will happily set you up elsewhere if you would prefer.”

“The temple will be fine, thank you.”

I followed Lorus through a pointed archway embedded into the cap. On the other side is a wide, circular plaza, ringed with flawless buildings. Clean and delicate, Telredor is a sharp departure from the murky wilderness. The houses and communal structures (efficiently and seamlessly built into the zangarstalk) look almost like sea creatures, their walls curved and segmented. Telredor bears scarcely any resemblance to the Temple of Telhamat. The architecture in Telhamat is imposing and monolithic, like a fortress. In contrast, the structures in Telredor possess an airy and ephemeral quality.

The plaza’s center is graced by a towering statue erected on a fountain. Carved with exquisite detail, the statue shows two children and a woman, all of them draenei. The woman is pouring water from a jar. All three figures bear radiant and hopeful smiles. Though the draenei typically favor abstract art, they can do remarkable work in more representational styles.

“I see you’ve noticed Gracious Renewal,” remarked Lorus, pointing to the fountain.

“It’s a beautiful piece of work. When was it built?”

“Quite recently, around the time that Velen reclaimed the Exodar and our anchorites returned to Shattrath. Before then, we lacked the resources for such a project. Gracious Renewal shows how, through community and faith (faith being a prerequisite for a strong community), we were able to rebuild from even the worst disaster. Look close; do you see how little the children in the fountain resemble the woman?”

I studied the fountain for a bit. In truth, I could not really tell the difference, though it was undoubtedly clear to draenic eyes.

“The designers did that to indicate that the woman is not the mother of the children. However, all three are part of the Most Holy Light, something that transcends family. Most likely their biological mother is dead, as are her biological children. Yet they stand together, boldly facing the future.”

I walked down a ramp into the plaza, townsfolk waving and calling out to me as I walked. I’ll admit that I always feel a bit guilty entering draenic towns in disguise. I wonder if I really deserve their unparalleled hospitality. Even so, circumstances gave me no other option. Lorus took me to the temple and then returned to his post. The temple was clearly older than the rest of the city, and looked more like the constructions I’d seen in Telhamat.

A young anchorite welcomed me to the temple and showed me to the guest quarters. The sanctuary is dim and plainly furnished though quite clean. A row of bunk beds fill one wing of the temple. I idled there for a bit before exploring Telredor.

Telredor began as a small monastic community on the fringe of draenic society. Established shortly after the Ogre War, the draenei built Telredor in order to supply missionary expeditions headed to the east and north. Telredor was instrumental in the foundation of the Temple of Telhamat. Sadly, Telredor never really lived up to its promise. Telhamat soon became self-sufficient and the draenei never got around to sending missions to the north. As such, only pilgrims on their way to Telhamat ever stopped in Telredor.

The Prophet Velen ensured that Telredor was maintained; he saw it as being one of two potential sanctuaries for the draenei in the event of disaster. For the curious, the other choice was a town called Sanaa which was probably annihilated during the Breaking. The Prophet chose wisely, and Telredor ended up harboring draenic refugees from the Horde War.

Just as I’d thought, Telredor was not nearly big enough to shelter all of them. Several refugee camps existed throughout Zangarmarsh, the biggest located below and around Telredor. The city proper was largely uninhabited during this time, as the draenei sought to avoid social stratification within the unmutated population. The monastery did act as a sort of nerve center for the refugee network.

Many draenei perished. Others mutated and were relocated to special camps, eventually turning into the Broken and Lost One tribes that populate Outland. When the draenei reclaimed Shattrath a few years ago, many of the normal ones left Zangarmarsh in order to salvage their old capital. Not long after, some departed to take the Exodar.

Telredor today has a much bigger population than it did before the war. The draenei who remained built the town that I saw. The buildings use zangarstalk planks to support thin plates of sanaum, explaining Telredor’s distinct architecture. Sanaum is difficult to make, and the mushroom isn't strong enough to support an entire town made of the stuff.

Homes and public structures are crammed together in the mushroom cap. The draenei utilize coiling passages to save space. Telredor really cannot get any bigger, though its confusing layout makes it seem larger than its actual size.

“I thank the Infinitely Holy Light every day that I live here. There is much camaraderie here in Telredor, the result of having survived so much suffering.”

I was speaking with a young draenei woman named Nyxa. Nyxa served Telredor in a bureaucratic capacity. Having learned fluent Common from Alliance Expeditionary Force survivors, she helped to manage Telredor’s dealings with other Alliance factions. We met inside a small, bright office. A kettle of tea steamed on a hot plate at her desk. Pouring two cups, she offered one to me.

“Were you born on Draenor?” I asked.

“In Shattrath City, yes. Most of my Collective was killed in the orcish attack. I barely escaped with my life.”

“I’m sorry for your loss.”

“All draenei experienced loss during that time. There was nothing special about me. Besides, I feel joyous living here! Telredor is a spiritual sanctuary as well as a physical one. Here I can wait until I grow stronger, and am able to better serve the Most Holy Light.”

“A noble goal. Have you ever returned to Shattrath City?”

“No. I am reluctant to leave the community here. Do you know of the ashem?”

“Yes,” I said, thinking of the emotionally distraught draenei cut off from the religious community.

“I am not ashem. Nor are the other permanent residents here. However, the Horde War shook our faith. This is an unforeseen generational problem. A few of us who were born and raised on Draenor could not adapt to the trials of warfare and persecution. Older draenei are used to hopping from world to world. Here, we had settled in and felt comfortable.” Nyxa sighed.

“This is a common issue among your generation?”

“Far from common, but my generation does have difficulty. Those affected are called kodei, or Confused Ones. The sages believe that we kodei became too attached to material things like cities and comfort. We reacted badly when deprived of them.”

“I’d hardly consider the draenei a materialistic people.”

“I fear that the kodei were. Still, there is good news. Weak though I am, my faith grows stronger every day.”

“I’m glad to hear that. Do you intend to leave eventually?”

“Yes. I have already visited Telhamat and the Cenarion Refuge. One day, when I know I can look upon an orc without feeling hatred in my heart, I shall go back to Shattrath City.”

It must be remembered that the kodei are only materialistic by draenic standards. The fact that they had grown too used to physical comfort was simply the result of establishing a permanent home. By human standards, the kodei would still be counted among the most spiritual people.

As I learned more about it, I began to suspect that the draenei overemphasized the significance of the kodei phenomenon. Many of the young draenei traumatized by the Horde War still went on to Shattrath or the Exodar. Only a very few were encouraged to stay behind in Telredor. Nor is such behavior exclusive to the young; a small number of older draenei were similarly affected.

At the same time, it must be noted that most of those who turned Broken or Lost came from the Draenor-born generation. These mutations occurred before the kodei phenomenon was documented. Many believe that, had the transformations not occurred, the Broken and Lost would have ended up like Nyxa. While this evidence is hardly conclusive, it is worth pondering.

This generation is also unique in being the first (and hopefully last) to witness the near-extermination of the draenei race. Demons have always hunted the draenei, but only the orcs defeated them. Even so, most of those labeled kodei quickly overcome their inner turmoil.

I spent the next few days learning about Zangarmarsh’s recent history. Sull’s account was basically accurate. The Wrekt came to power at some point after the Breaking and built their kingdom by enslaving the Lost One tribes. The draenei knew of this, but did nothing. This was not because of apathy. The draenei simply lacked the resources to effectively fight the Wrekt. For their part, the Wrekt avoided Telredor. When Illidan came he initially attempted to convince the Wrekt to join his fledgling empire. The Wrekt refused and were soon conquered by the naga. The nearby Dreghood Tribe met a similar fate at the hands of other Illidari.

I managed to get a firsthand account of the Wrekt Tribe’s rise and fall on my third day at Telredor. A handful of Wrekt refugees had returned to Telredor after their conquest, asking for sanctuary. Since the Broken had been accepted back into the fold, the draenei gave these Wrekt a cautious welcome. These refugees (six of them in total) dwell in a small but cozy chamber that looks out onto the marsh.

These Broken were watched over by none other than Vuunos, the priest mentioned by Sull. Vuunos cut an impressive figure and spoke in a voice like rumbling stone. Equal parts fierce general, stern preacher, and kindly father, I could easily see why the Broken looked up to him. Though I badly wanted to tell him about Sull, I decided against it for fear it would expose the Talus persona.

Vuunos insisted on moderating the interview.

“You must understand that my duty is to bring the Broken back into the joy of the Infinitely Holy Light. However, speaking of the Wrekt Nation is quite painful for them. I cannot allow them to slide back into misery. That is why I must be present to help if needed.”

Vuunos introduced me to Makon. Makon hardly looked like he was once the terror of Zangarmarsh. Though powerfully built, his solemn and humble demeanor reminded me more of a penitent than a warrior. Yet he had been the greatest warrior of his tribe.

“We Broken left Telredor into a world of fear and confusion. None of us could find the Light. We were once draenei, but no longer,” reminisced Makon.

“You are still a brother in the Light, dear Makon,” reminded Vuunos.

“I know. We did not know then.”

I wondered if Makon ever resented the draenei for expelling the Broken. If so, was he ever allowed to voice the resentment?

“Among us was a Broken who had once been a vindicator; Koshen was his name. He said that we had to make things right, to punish those who persecuted us. Koshen led us to Orebor Harborage.”

“Orebor Harborage is an old fort built by our people during the Ogre War,” interjected Vuunos.

“I swore fealty to Koshen. To establish ourselves we fought the ogres to the north. Yet we knew that the true enemy, the orcs, resided in the south. Koshen said that we had to strengthen our position before we assailed the Horde. His words inspired us to conquer the Lost Ones.”

“Did you know that the Lost Ones were related to you?” I asked.

“We did. Koshen said they had fallen further than we. The Lost Ones were nothing to us, and even now the true draenei make little effort to help them—”

“The Lost Ones who seek help receive it Makon. You know that,” chided Vuunos.

“Yes. I apologize.”

“The Lost Ones have fallen further, as you said. But the way of the Light is not to kill them. We must take care around them, lest their misery spread to us, but those Lost Ones receptive to the Light should be taught.”

“Yes, Brother Vuunos. I will remember.” Makon lowered his face into his hands and began to cry. Vuunos immediately embraced the sobbing Broken, speaking soft words of hope.

“I apologize Brother Talus. I think this interview must end. If you would go to the foyer and wait, I’ll explain more.”

I went to the anteroom and watched the rain fall on the fungal canopy outside. I recalled the Broken I’d met in Exodar, led by Nobundo. I knew that most of them hailed from the Broken camps nearest Telredor. They had never really formed their own tribe. Certainly they showed the most inclination for self-improvement. The Dreghood and Wrekt only returned to the draenei after suffering total defeat.

Something about Makon’s tale had disturbed me. The draenei had cast out the Broken, fearing that their mental state would harm draenic society. Given the empathic tendencies of the draenei, this was not unreasonable. But left to their own devices in the wastes of Outland, the Broken had no choice but to turn savage.

Traveling in Outland soon reveals just how much damage these Broken caused. Their marauders plagued many regions, and the Wrekt were hardly the worst. How much of this cruelty was due to the Broken’s mental condition, and how much came from their exclusion, is open to debate. What is certain is that Illidan found the Broken to be a great resource. Admittedly he has largely wasted the Broken by enslaving them, but they play a key role in his petty kingdom. Had Illidan done more to win the favor of the Broken, his position in Outland could well be unassailable.

“We sent an anchorite over to Orebor, to convince the Wrekt to stop their violence. I do not know if she ever reached them.”

Vuunos had finished comforting Makon, and had returned to me.

“I suppose you would not have really had the resources to send more than one,” I said.

“You are correct. Makon’s story ends with the naga coming to Zangarmarsh. To their credit, the Wrekt refused to join Illidan. Most are now slaves.”

“Is it difficult being with them?”

“It is, but Nobundo’s partial redemption has proven that the Broken are undeniably a part of the Most Holy Light. We can accept small groups of them. Our goal is to cultivate joy in their hearts and, when the time is right, return them to their brethren. Hopefully the Light will spread from there.”

“What about shamanism? From my understanding the Wrekt already practiced a corrupted form.”

“A foul and nearly unrecognizable form. Farseer Saamo, one of Nobundo’s disciples, teaches them shamanism that is compatible with the Most Holy Light.”

Vuunos sighed.

“Making the Broken leave was a terrible thing, but we had no choice. Happiness was in short supply during that time, and we could not afford to lose any of it.”

I voiced agreement with Vuunos, but I had my doubts. If draenic faith is so great, couldn’t they have overcome the sorrow of the Broken? I cannot help but think that both the draenei and Outland would be in better shape if the Broken had not been made to leave. Certainly their expulsion caused them and their neighbors to suffer great misery, decreasing the universal level of happiness. Then again, I am neither a draenei nor a theologian. Perhaps keeping the Broken would have destroyed the draenei.

To put it simply, there are no easy answers when it comes to the Broken.

Wow, you really paint the whole Broken and Lost Ones as a difficult problem. I always did have the same doubts as Destron had, that the banishment of the Broken was kinda contradictory to the draenei beliefs.

ReplyDeleteAll these people that Destron befriends... and how his disguise works so well. I'd be interested to see how some of the alliance he befriends react if his disguise proved faulty somehow. Especially the Draenei, how would they react to such a sentient walking dead.

Wewt, can't wait to see some Sporeggar stories, go go mushroom men!

Excellent, you've really outdone yourself, Destron! I love the way that you have captured the psychology of the draenei and the subtle differences between the untainted draenei and their two devolutionary subclasses. I've been waiting on tenterhooks for the Zangarmarsh stories, and so far have not been disappointed! It would be interesting to see how Destron interacts with the naga, if at all possible. If he perhaps encounters a lone, wounded naga who is near death and willing to talk, or whatever. Just a suggestion. If you want a little helpful criticism regarding grammar, watch out for missing commas: I noticed in a few places throughout the travelogue that you forgot to add commas when using direct address. For instance, when he goes to Telredor, "Thank you Lorus,..." should be, "Thank you, Lorus,..." But otherwise I have no complaints whatsoever. Keep it up!

ReplyDeleteThanks, I appreciate the comments. Unfortunately, I won't really have time for a meeting between Destron and the naga. The zones in Outland are simply too big for me to cover everything, and I'm going to have my hands full with the Zabra'jin trolls and the sporeloks.

ReplyDeleteI'm not sure if you've read the Azshara section, but Destron does interact with the naga there.

Also, thanks for pointing out the grammar issues. Commas seem to be my Achilles' heel; I either overuse them, or neglect to use them when I should. Still, comments like these help me improve.

ReplyDeleteWow that was an awesome read. Thank you very much for the enjoyment and keep em coming.

ReplyDeleteThis was quite creepy.

ReplyDelete